Introduction

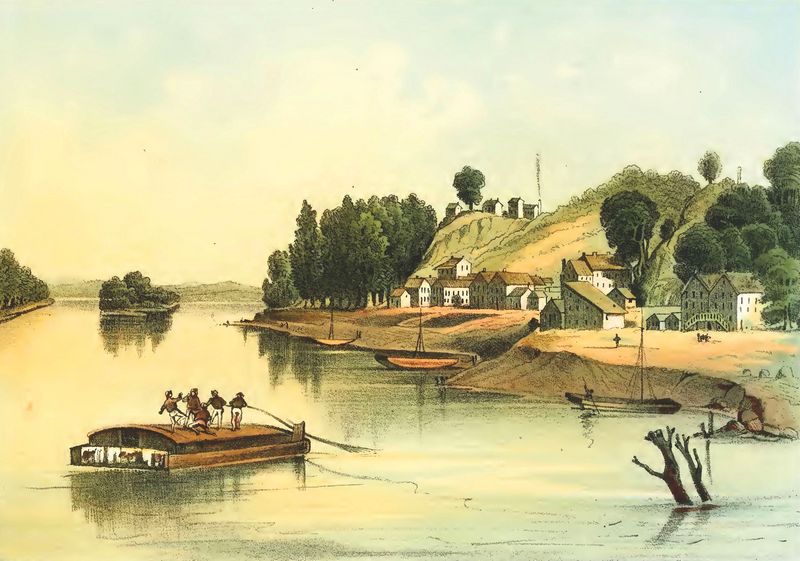

A small town perched on top of a bluff overlooking the river, Warsaw has an interesting history and impressive 19th century buildings that make it a pleasant place to stop and visit.

Visitor Information

Direct your questions to Warsaw’s local government office.

History

Before there was a Warsaw, there were a couple of frontier forts built on the bluff overlooking the Mississippi River. In late 1814, near the end of the War of 1812, Major Zachary Taylor, a future US president, oversaw construction of Fort Johnson to house his company of 430 soldiers. The fort, however, was abandoned just a few weeks after it was built because it was constantly harassed by Sauk and British warriors, and it was difficult to supply.

A military encampment called Cantonment Davis was established the following year and charged with building a new fort that would be more accessible and that was intended to protect the growing fur trade in the region. Fort Edwards was completed in 1817.

In 1818, the US government opened a fur post, and three years later John Jacob Astor set up his own post, putting Russell Farnham in charge. Farnham got around. Besides Warsaw, he operated trading posts at locations that would eventually become the cities of Rock Island, Muscatine, and Keokuk. The US government closed its fur post in 1822, and when Fort Edwards closed two years later, Farnham moved the trading post into the buildings of the former fort. Farnham’s post closed in 1832, after he died of cholera in St. Louis.

A few former soldiers from the fort stuck around and had a hand in starting the new village, including John R. Wilcox, a former lieutenant at the fort, and Mark Aldrich, who was a clerk with Farnham’s trading post.

The official group of founders was a fairly large one and included people from around the US and a few other countries. In 1834, they platted the village and called it Warsaw. Over the years, many have speculated about why that early group decided to honor the capital city of Poland. One theory is that a novel called Thaddeus of Warsaw was popular at the time, but the reality is that there just may not be a good explanation, or one that we will ever know. Likewise, the origin of the city’s longtime nickname—Spunky Point—isn’t clear at all, either, but it is a fun nickname, one that appears on a city street and even a center for senior citizens. It would also be a great name for a local brewery. You don’t even have to pay me royalties for the idea.

Just a few years after its founding, Warsaw was at the center of the hostility to the growing Mormon community at Nauvoo. Warsaw was a busy river town populated by people who argued regularly about concepts like individual liberty and the democratic process. They didn’t like what they saw happening in Nauvoo, which they saw as an increasingly powerful theocratic government that wasn’t ultimately accountable to its citizens. The intensity of the dispute between Warsaw and Nauvoo sometimes erupted in violent confrontations that required the governor’s intervention to defuse.

One of the most vocal opponents of the Mormon-led government in Nauvoo was the editor of the Warsaw Signal, Thomas Sharp, who used his newspaper as a forum to rail against the Mormon leadership, often with inflammatory language. Sharpe’s harsh editorials probably incited some of the anti-Mormon violence in the 1840s. Sharpe, in fact, was almost certainly part of the group that broke into the Carthage jail and killed Joseph and Hyrum Smith. He was among those charged with the murders, but Sharpe and all the others were acquitted by a sympathetic jury.

After the Mormons were driven out of Nauvoo, Warsaw quieted down and grew into an important river port, thanks to its position at the downstream end of the Des Moines rapids. Thomas Sharp would even serve three terms as mayor of Warsaw in the 1850s.

Many of the earliest citizens were English and Irish; they were followed by a significant number of Germans. The terrain with its many ravines made it difficult to build a well-connected city, which may be why so many distinct neighborhoods developed. Stumptown was nearly a mile south of the business district, in an area that had been heavily deforested. Frenchtown was east of Stumptown, and, besides being home to residents of French ancestry who arrived in the 1850s, also had a school for black children. Calftown was northeast of Frenchtown; Charles Hoppe ran a slaughterhouse there.

By 1870, Warsaw was a hopping place. Its 3,500 residents were served by a couple of flour mills, a woolen mill, packing houses, and several breweries and distilleries. The saloons were no doubt very busy, but saloon owners were not allowed to hold public office and many churches refused them membership. Residents could ride a ferry across the river to Alexandria, Missouri (until 1932). City leaders were feeling so good that on December 15, 1869 the Warsaw city council passed a resolution encouraging the US government to relocate the national capital to Warsaw.

Warsaw’s fortunes were very closely tied to the river trade, thanks largely to the barrier posed by the Des Moines Rapids. When a canal was finished that allowed boats to bypass the rapids, most boats no longer needed to stop at Warsaw. This triggered a slow but steady decline in the city’s fortunes. The city also lost out when it failed to secure good railroad connections.

Warsaw was the childhood home of John Hay, one of the 19th century’s best known statesmen/writers. Hay was the son of Dr. Charles Hay, an anti-slavery Whig from Kentucky, and Helen Leonard Hay, a native of Rhode Island. The family moved to Warsaw in 1841 when John was three years old and the city had maybe 300 residents.

Hay was educated in Warsaw and was an eager learner. By age 12 he knew a little Greek, was fluent in German, and had learned a lot of American slang from the steamboat men at Warsaw. His uncle, Colonel Milton Hay, brought him to Pittsfield, Illinois to study at a private school, then helped to pay his tuition at Brown University where his classmates elected him class poet. Hay went back to Warsaw for a couple of years after graduating, then went to Springfield, Illinois to help his uncle who was working on Abraham Lincoln’s campaign for President.

Hay’s affection for his hometown remained strong. Not long after moving to Washington, DC, he wrote the following to a friend back in Warsaw:

Warsaw dull? It shines before my eyes like a social paradise compared with this miserable sprawling village which imagines itself a city because it is wicked, as a boy thinks he is a man when he smokes and swears. I wish I could by wishing find myself in Warsaw. (From The Boyhood of John Jay, in The Century, Vol. 78, p. 453; letter dated Nov 29, 1860)

Hay served as Lincoln’s private secretary during the Civil War and grew quite close to the President. After Lincoln died, Hay bounced around Europe and the US for a while, working in the diplomatic services and resting at home in Warsaw before being hired by Horace Greeley to write for the New York Tribune. In 1874, he married Clara Stone, the daughter of a wealthy Cleveland industrialist. He and long-time friend John Nicolay wrote Abraham Lincoln: A History, a 10-volume work published in 1890 that is still influential today. Hay also wrote Pike County Ballads, a collection of poems using some of that vernacular speech he learned from rivermen; it sold quite well. Hay’s book The Bread-Winners was a controversial, anti-labor narrative that he published anonymously; the inspiration for the book was Hay’s own experience running his father-in-law’s company during a period of labor unrest in the 1870s.

After 15 years out of politics, President William McKinley appointed Hay Ambassador to England, then less than two years later, chose Hay as his Secretary of State, a post Hay kept when Teddy Roosevelt became president after McKinley’s assassination. Hay played a key role in smoothing the diplomatic path for the construction of the Panama Canal and in protecting American trade interests in China. Hay died in New Hampshire on July 1, 1905 while still serving as Secretary of State; he was 66.

Warsaw today is much like the Warsaw of the past century: a small city holding on to its historic connection to the Mississippi River, searching for ways to create jobs and boost its economy, even as the population continues a slow decline. Warsaw has retained an impressive collection of 19th century architecture—most of the town has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places since 1977 and much of the architecture is easily viewed.

Exploring the Area

The Warsaw Museum (401 Main St.) showcases the city’s rich and varied history; it has limited hours but you can call one of the contact people listed on the front door to arrange a tour.

An obelisk stands at the north end of town as a memorial for Fort Edwards (north end of 3rd St.); it comes with pretty good views of the river.

Warsaw has a great and varied collection of 19th century architecture; there’s a self-guided tour published in 1984 that, if you can find a copy, is worth the time to check out. Here are some highlights:

- The castle-like Warsaw Brewery building (900 N. 6th St.) was completed in 1860 for the Popel-Giller Company, then rebuilt and expanded in 1908 for the Warsaw Brewing Company. The building is currently unoccupied.

- There’s another beautiful but neglected historic building down in the bottoms (1401 S. Water St.). Originally built for the Woolen Manufacturing Company in 1866, it was later occupied by the Huiskamp Shoe Company, then in 1936 by Grant Storage Battery Company.

- Many of the buildings associated with John Hay are no longer around, but the simple structure that served as a school when he was a child is still standing (240 N. 4th St.). Built in 1835, it was used as school until 1903 and then as an American Legion post for many years.

Parks Along the Mississippi River

Warsaw Riverfront Park (1000 Water St.; 217.256.3214) has pleasant places to picnic next to the river.

Sports & Recreation

Kibbe Life Science Station (Warsaw Rd.; 217.256.4519) has 12 miles of hiking through the 222 acres of bluffs and forests near Warsaw owned and managed by Western Illinois University.

An adjacent 1458 acres are owned by the State of Illinois as Cedar Glen State Natural Area (217.453.2512); it includes bottomland forests, savanna, and forested bluffs. Cedar Glen is popular with hunters in season and is closed to the public between November 1 and March 1 to protect roosting bald eagles.

Entertainment and Events

Farmers Market

Warsaw hosts a farmers market on Thursday afternoons from May through October at Ralston Park (430 N. 4th St.).

**Looking for more places to visit along the Mississippi River? Check out Road Tripping Along the Great River Road, Vol. 1. Click the link above for more. Disclosure: This website may be compensated for linking to other sites or for sales of products we link to.

Where to Sleep

Camping

Warsaw Riverfront Park/Goose Landing (1000 Water St.; 217.256.3214) offers 20 sites next to the river, all with water and electricity.

Resources

- Warsaw Public Library: 1025 Webster St.; 217.256.3417.

- Post Office: 520 Main St.

- Newspaper: Hancock County Journal-Pilot

Community-supported writing

If you like the content at the Mississippi Valley Traveler, please consider showing your support by making a one-time contribution or by subscribing through Patreon. Book sales don’t fully cover my costs, and I don’t have deep corporate pockets bankrolling my work. I’m a freelance writer bringing you stories about life along the Mississippi River. I need your help to keep this going. Every dollar you contribute makes it possible for me to continue sharing stories about America’s Greatest River!

Warsaw Photographs

©Dean Klinkenberg, 2015,2019