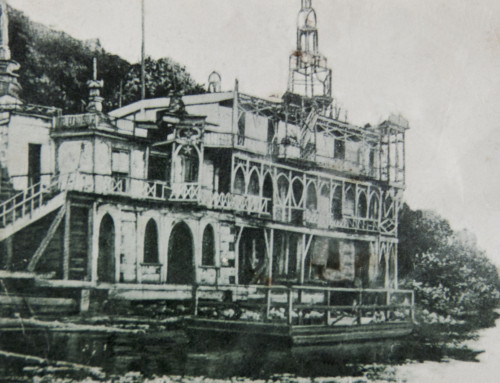

When the Headwaters Dam Project was completed in the early 20th century, water levels went up on many lakes in northern Minnesota, including big ones like Cass and Winnibigoshish. The dams were supposed to increase the depth of the Mississippi River south of St. Paul to improve navigation for bigger boats during low water periods. It didn’t work. While the Twin Cities saw a modest increase in river depth, enough to give a good boost to the water power-dependent mills in Minneapolis, the dams made no difference further south.

In northern Minnesota, however, the higher water levels wiped out much of the habitat for wild rice and in the process further diminishing what remained of the traditional Ojibwe lifestyle. In 1985, the federal government and the Ojibwe nation agreed to settle a century-long dispute over the dam project in which the federal government took, without the Ojibwe’s consent, some reservation land to build the dams, flooded other parts of reservation lands, and destroyed thousands of acres of those rice beds. In the late 19th century, the federal government offered the Ojibwe $150,000 as compensation, an offer the Ojibwe considered ridiculously inadequate; one hundred years later, the parties reached an out-of-court settlement for $3.3 million.

I was reminded of that story as I talked to people about this year’s wild rice harvest. Wild rice has bounced back, in part because the Corps of Engineers has been pressured to manage water levels in a way that creates more favorable growing conditions. Regardless, this year was not a good one for wild rice, as northern Minnesota had much higher than average snow and rain, which caused higher than normal water levels on the lakes and fewer patches of water less than three feet deep where wild rice thrives.

All was not lost, however, as river rice seemed to be doing pretty well. As you may recall, I went in a canoe on the Mississippi River in late August to watch and to participate in a wild rice harvest. While our two pounds of raw rice won’t impress many people, it gave me just enough to get a taste of the harvest. It was also enough for me to try processing it the traditional way.

Freshly harvested wild rice is damp and smells like freshly cut grass and may come with a few hitchhikers in the form of worms and insects. The rice will rot pretty quickly if it is not dried soon after harvesting, so the first thing I had to do was find somewhere to lay it out. Lucky for me, the place where I was staying, Ruttger’s Resort in Bemidji, let me use an empty meeting room. I laid out some plastic bags and set the rice on top of it, then carefully picked out all the bug I could so whoever used the room next didn’t have any uninvited guests. By the next morning, it had dried out well enough to gather it into a canvass bag and put it in my backseat for the drive home.

Once the rice is dry, it has to be roasted. Sometimes rice is roasted in a big cast iron pot hung over a wood fire where it is cooked for 10-15 minutes (stirring constantly, in case you’re taking notes). I didn’t have a big cast iron pot, so I roasted small batches over high heat in a dry wok, filling the kitchen with the scent of roasted corn as the rice turned light brown.

The roasting process separates the kernels from the hulls, so the next step is removing those kernels from the hulls. There are many ways to do this, if you know what you’re doing, which I don’t. The Ojibwe would place a deer skin in a hole dug about 18 inches deep in the ground, pour the rice on top, then walk on it, with very clean feet or moccasins. Modern machinery can vibrate or press the kernels out of the hull.

I didn’t have any of those tools, so I put all the rice into a medium-sized cooler, washed my bare feet, and stepped in to the cooler. I stomped and patted and ran in place on top of the rice, occasionally bracing myself with the chair next to me. After 15 minutes of this, I still didn’t see many of the dark inner kernels, so I gave up. The problem with the cooler was probably that the plastic surface was too slick and didn’t generate enough resistance to force the kernels out. Either that or I need rougher feet.

The next method I tried was picking kernels out by hand, partly to see if I had roasted the rice properly and partly to figure out how long that process might take. The kernels came out easily, so I figured roasting wasn’t the problem. I probably could have hulled each blade of rice by hand, but, by the time I was done I’d be blind and on Medicare.

The next hulling method I tried was pressing the rice using a rolling pin, first on a Silestone countertop, then on the countertop but with the rice wrapped in a dish towel. Both of these worked fairly well, but there were still quite a few kernels left in the hulls, plus I broke a lot of them into small fragments, so that’s not the answer, either.

Assuming I can figure out a method to finish the hulling, the next step is winnowing to separate the empty hulls from the kernels. One of the traditional ways to do this is to place the rice in a shallow basket and gently toss it around, so that the empty hulls, which are much lighter than the kernels, will catch a breeze and blow away, leaving you with dinner. Some people winnow by laying everything on a table and manually picking out the kernels. That seemed tedious, so I put the small batch of rice I hulled with the rolling pin into a shallow wicker basket and tossed it around in front of a fan on the back porch. It looks so easy, but it takes concentration and coordination or you’ll end up tossing out the kernels accidentally, which I did more than once. I finally got the hang of it, though, and after at least ten minutes of tossing, I got rid of most of the empty hulls.

So I have about an ounce of processed rice and a lot more raw rice waiting to be hulled and am kinda stuck about what to try next. I’ll figure something out, though. This is hard work, processing wild rice the traditional way. All that work yields a return of roughly 40%, meaning that 100 pounds of raw grain will yield about 40 pounds of edible rice. My two pounds of raw rice will eventually give me about 13 ounces, which is still enough to serve as a side dish for a dozen people. Plus, my rice comes with a good story.

The ritual of harvesting, processing, and eating wild rice is an ancient one that connected me to an old way of living, one where people adapt to the natural world instead of trying to bend it to our will, and one where hard work and perseverance is rewarded with food that actually tastes like something other than the oil it is fried in..

In 21st century America, our food is about speed and predictability. We don’t make room in our lives for food that takes time to cook, much less to grow and process. We value convenience over everything else, and, because of that, across much of America today, food is sterile and homogeneous (like our newer neighborhoods) but at least it is served quickly. And what have we gotten from this? A few extra minutes each day to text and surf the ‘net and diabetes. It hasn’t always been so.

For the Ojibwe, as for many Native Americans, food was not merely sustenance but part of a way of life that was linked to the rhythm of the seasons and helped define who they were as people. Few foods were more central to their life and identity than wild rice, which is why the Ojibwe fought hard for over a century to protect it. Is there any food in your life today that is so central to who you are, that has been passed down through generations to you, that you would be willing to fight for a century to protect? (If your answer is “a Big Mac,” give me your address so I can set up an intervention.)

I don’t expect you to get in a canoe and harvest your own rice (if you do, be sure to get a permit first!), but the next time you eat it, which I hope is soon, you’ll know a bit more about the big history of this deceptively simple food. And, as you lift a forkful of wild rice to your mouth, maybe you’ll also pause for a millisecond to give thanks to those generations who made it possible for that wild rice to reach your table.

Did you miss part 1? Go back and read about harvesting wild rice.

And now a few tips.

On buying wild rice:

Prices vary depending upon how and where it is harvested. If you see “wild rice” that is under $4 a pound, it was grown commercially, then harvested and processed mechanically. At the top end, often around $9 a pound, is wild rice that actually grew in the wild and was harvested by hand using traditional methods, usually by Native Americans. Some of this rice is also processed by hand but most of the rice you’ll see for sale was processed mechanically. Many people consider the commercially grown version to be an inferior product with a less satisfying flavor. I haven’t personally taste-tested the two grades, so I’ll let you tell me what you think.

You will also see bags labeled “broken” that are kernels that split apart during processing. This is still quite tasty to eat but it is less desirable than having intact kernels, so you will pay less for it.

Storage:

Keep it dry and cool in a sealed container and will it keep indefinitely, with no loss of flavor or nutritional value, all without the use of preservatives. Isn’t nature cool?

Basic preparation of wild rice:

It’s not really hard to cook, but, unlike regular rice, cooking times can vary widely for a variety of reasons (darker kernels take longer to cook, for example), so you need to lift the lid occasionally and test the consistency to avoid getting a mushy mess.

Begin by placing 1 cup of wild rice in a strainer and rinsing it in cold water until the water runs clear. Put the rinsed rice into a pot and add 2 cups of water and ½ teaspoon of salt; for additional flavor, substitute chicken stock or turkey stock for the water. Bring to a boil, then cover and let simmer for up to 45 minutes. Don’t let it dry out while cooking. You may want to check the consistency of the rice around the 30 minute mark. Broken rice and lighter colored wild rice could be done in 20-30 minutes instead of 45. Wild rice should have a slight crispness to it, not unlike pasta cooked al dente, just don’t let it get mushy. Yuk.

If you cooked too much, leftovers freeze well. The best way to reheat frozen rice is to place it in a double boiler for a few minutes. Wild rice makes a nice side dish, but it is versatile enough for a variety of uses, like in chicken soup, stuffing, or quiche; you can easily build hotdish around it. Let your imagination take over.

**Read more about the places in northern Minnesota in Road Tripping Along the Great River Road, Vol. 1 and the Headwaters Region Guide. Click the links above for more. Disclosure: This website may be compensated for linking to other sites or for sales of products we link to.

- Pokegama Dam, one of the Headwaters Dams

- Wild rice set out to dry

- Roasting the rice to dry it completely

- Trying to remove the kernels from the hulls

- Winnowing

- Fully processed and ready to cook

© Dean Klinkenberg, 2011

Community-supported writing

If you like the content at the Mississippi Valley Traveler, please consider showing your support by making a one-time contribution or by subscribing through Patreon. Book sales don’t fully cover my costs, and I don’t have deep corporate pockets bankrolling my work. I’m a freelance writer bringing you stories about life along the Mississippi River. I need your help to keep this going. Every dollar you contribute makes it possible for me to continue sharing stories about America’s Greatest River!