Introduction

Most of Arsenal Island is a military installation, but there are several sites open to visitors. Just be prepared to complete a screening procedure.

All visitors must first check in at the Visitors Center at the Moline gate and get a pass. Enter from River Drive in Moline and turn right before you reach the checkpoint, then follow the signs. You will need to show a photo ID and undergo a criminal background check. Once you are approved (the process takes a few minutes but you may have to wait in line for a while), you can enter the Arsenal grounds with a pass that is good for a year.

You can’t get a pass, however, if you are a foreign national (unless you are visiting on official business) or if you are under 18 years of age and not accompanied by an adult. If the criminal background check isn’t favorable, you will also be denied access.

Visitor Information

Direct your questions to Visit Quad Cities (563.322.3911).

- NOTE: See the Quad Cities overview for regional information, including more detail on tourism centers, festivals, and getting around.

History

The United States acquired title to Arsenal Island in 1804 through a treaty with Sauk and Mesquakie Indians, although the validity of the treaty was challenged by those Indian nations for many years. The first military outpost, Fort Armstrong, was built on the western end of the island in 1816. George Davenport ran the fort’s commissary and lived a short distance away. The fort served as military headquarters during the Black Hawk War but closed just four years after the war ended. The Army used the fort’s buildings as a weapons depot until 1845. The last remnants of the fort were razed in 1864.

The U.S. government lost interest in the island until the Civil War. After Confederate troops destroyed the Harper’s Ferry Armory in 1861, the Union needed a safe location to store armaments. A lobbying effort by local officials coupled with astute political maneuvering persuaded Congress to create the Rock Island Arsenal in 1862. The new arsenal was quickly called to serve an unintended purpose: prison camp for captured Confederate soldiers. At its peak, nearly 8,600 Confederate soldiers were housed on the island. Rotating groups of Union soldiers served as prison guards, including a turn by the 108th Regiment, U.S. Colored Infantry. Between 1863 and 1865, about two thousand Confederate POWs died at the Arsenal Island camp, mostly from diseases such as smallpox and pneumonia.

Major Charles Kingsbury, the Arsenal’s first commander, began construction of the first building, now known as the Clock Tower, in 1863, but a number of logistic and financial challenges delayed completion until 1867. The Arsenal’s second commander, Brevet Brigadier General Thomas Rodman, laid out the grand plans that gave the installation its current shape: a group of ten large workshops, quarters for the commanding officer, and a bridge that would connect the island to Iowa. Rodman died unexpectedly in 1871, but his plans were completed by his successor, Lieutenant Colonel Daniel Flagler. The ten shops, each covering a full acre, were built with imposing limestone facades; they are still in use today. Quarters One, home for the commanding officer, was completed just after Rodman died. The ornate Italianate building has nineteen thousand square feet of living space, making it the second-largest single-family home in the government’s real-estate portfolio; only the White House is larger. The bridge Rodman envisioned was completed in 1872, then completely overhauled in 1896.

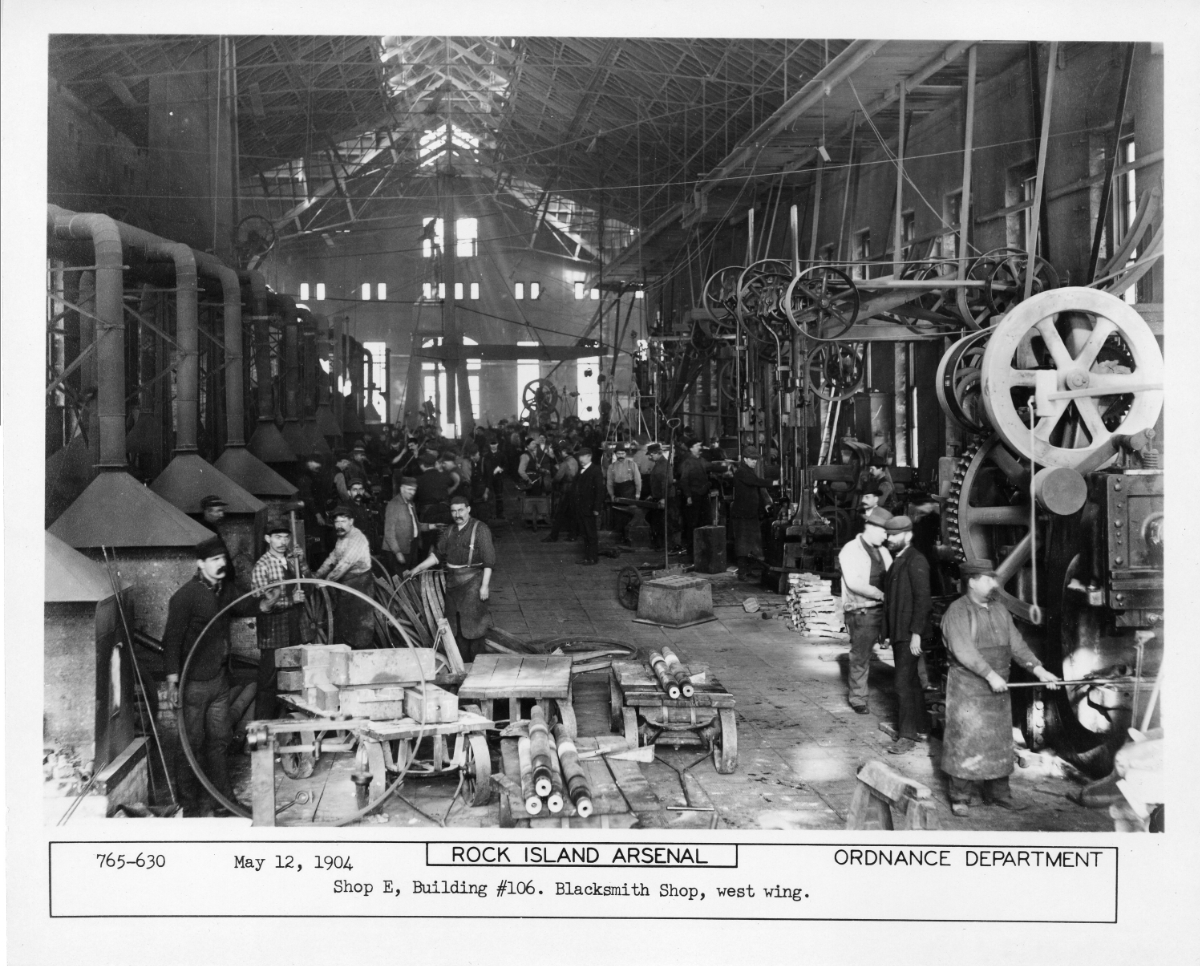

For the first dozen years of its existence, the Arsenal was only authorized to serve as a depot. In 1875, however, it manufactured its first items for the Army and continues to do so to this day. For the most part, the Arsenal has produced small arms like howitzers, rifles, rocket launchers, and machine guns, in addition to supplies like mess kits, harnesses, and canteen carriers. The main products manufactured at the Arsenal now are gun mounts, recoil mechanisms, artillery cartridges, and tools for field repairs. The Arsenal has been a major employer for the region since its inception but especially during war time. During WWII, employment peaked at nearly nineteen thousand but has more typically been around two thousand in peacetime.

Exploring the Area

Among the first sites you’ll pass are the Rock Island Confederate Cemetery and Rock Island National Cemetery. The Confederate Cemetery is the final resting place for nearly two thousand Confederate soldiers who died while imprisoned on the island during the Civil War. The national cemetery began in 1863 as the burial grounds for Union soldiers guarding that same Confederate prison camp. Over twenty-nine thousand veterans and their relatives are interred here. Both cemeteries are free and open daily from sunrise to sunset (309.782.2094).

Memorial Field (Rodman Ave. @ East Ave.; 309.782.5021) is an outdoor museum of sorts, with a collection of ordnance systems, including artillery pieces and rocket launchers. Most of the weapons on display were manufactured on the island at one time.

The Rock Island Arsenal Museum (North Ave.; 309.782.5021) is the second-oldest U.S. Army Museum; it has been open since 1905. The collection includes an impressive number and diversity of handguns, rifles, and other small arms. (NOTE: The museum is closed for renovations until late 2022.)

The Colonel George Davenport House (Hillman St.; 309.786.7336) was constructed in 1833 and was the center of civic life in the region for years: Rock Islanders plotted to get the county seat here, towns were platted, and leaders negotiated with railroad executives for a rail port. On July 4, 1845, Colonel Davenport was at home when several men entered the house. During the robbery, Davenport was shot and mortally wounded. The murder shocked and angered the community, which launched a massive manhunt. Six men were eventually caught and convicted. On October 29, just three months after the murder, three of the men were hanged in a public square before a large crowd. In a bizarre twist, the rope broke for one of the men and the executioner had to reload and try again, while fending off cries from the gallery that the broken rope was a sign from God to halt the execution. Even though several men were caught and executed for the crime, rumors persist to this day that Davenport’s murder was part of a larger conspiracy to kill him, although the motivation for such a conspiracy often varies from story to story.

At the far end of the island, the Mississippi River Visitor’s Center (Building 328, Rodman Ave.; 309.794.5338) hosts several displays that highlight Mississippi River ecology and commerce. This is also a good vantage point to watch barges pass through Lock #15, which was the first of twenty-nine built that aimed to tame the Mississippi River for navigation. In the Quad Cities, the completion of #15 buried the hazardous rapids and created a large lake that is popular with recreational boaters. The pool behind this dam is one of the most stable in the system; the water level only fluctuates by one to three feet, even during floods, an ironic turn of fate—from being one of the most hazardous stretches of the river to navigate to being one of the most dependable.

Tours

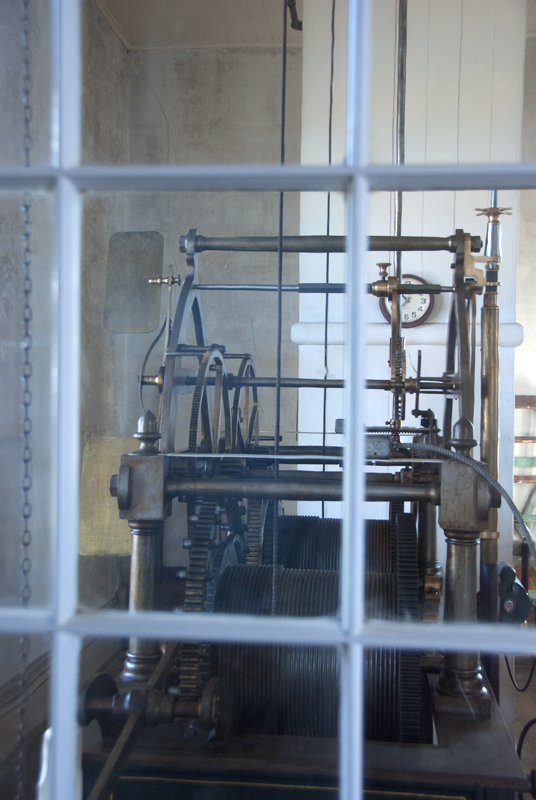

Just across the road from the visitor’s center, the Clock Tower rises six stories above the island. The tower was built of native limestone and was part of the first structure built for the Arsenal. The clock was purchased from New York-based A.S. Hotchkiss Company and installed in 1868. Each of the four clock faces is twelve feet in diameter; the minute hands are six feet long and the second hands are five feet long. The clock still has its original parts and still works. If the clock doesn’t interest you, the views from the top floor are the best in the Quad Cities. The Corps leads periodic tours through the Clock Tower. Call for times and to make a reservation (309.794.5338).

**Arsenal Island is covered in Road Tripping Along the Great River Road, Vol. 1. Click the link above for more. Disclosure: This website may be compensated for linking to other sites or for sales of products we link to.

Where to Go Next

Heading upriver? Check out Moline.

Heading downriver? Check out Rock Island.

Community-supported writing

If you like the content at the Mississippi Valley Traveler, please consider showing your support by making a one-time contribution or by subscribing through Patreon. Book sales don’t fully cover my costs, and I don’t have deep corporate pockets bankrolling my work. I’m a freelance writer bringing you stories about life along the Mississippi River. I need your help to keep this going. Every dollar you contribute makes it possible for me to continue sharing stories about America’s Greatest River!

Arsenal Island Photographs

©Dean Klinkenberg, 2009,2019