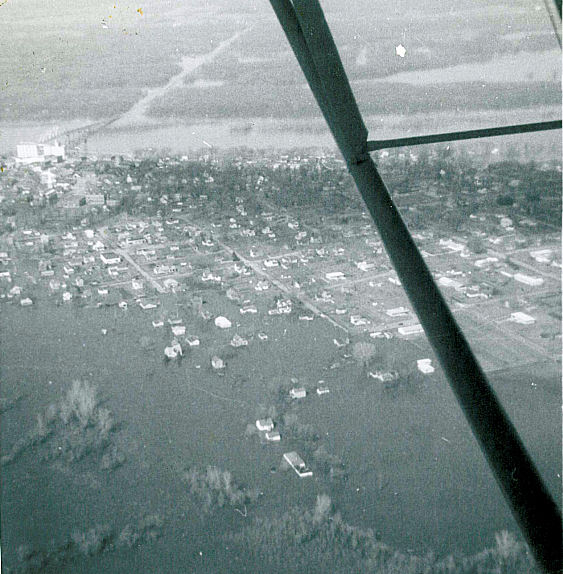

In April 1965, the Upper Mississippi River surged to heights never before recorded, threatening to swallow entire towns whole. This episode plunges you into the chaos as the perfect storm—deep snowpack, torrential rain, and frozen ground—transformed America’s greatest river into an unstoppable force.

Journey from the imperiled bridges of Minneapolis to the desperate fight for survival in Winona, where 1.3 million sandbags stood between 15,000 homes and the raging river. Experience the flood through the eyes of those who lived it—teenage volunteers working feverishly for $1.50 an hour, the Navy veteran who crawled through sewers to prevent catastrophic explosions, and the stubborn river dweller who, after losing everything declared, “Custer’s last stand is over.”

With 40,000 people displaced, 19 lives lost, and damages exceeding $1 billion in today’s dollars, the 1965 flood rewrote the relationship between river communities and the upper Mississippi. Yet most Americans know little about this watershed disaster.

Don’t miss this riveting account of nature’s raw power and human resilience in the face of overwhelming odds.

Show Notes

Presentation in Rochester Minnesota

Find Mississippi River Mayhem by Dean Klinkenberg wherever books are sold

Support the Show

If you are enjoying the podcast, please consider showing your support by making a one-time contribution or by supporting as a regular contributor through Patreon. Every dollar you contribute makes it possible for me to continue sharing stories about America’s Greatest River.

Don’t want to deal with Patreon? No worries. You can show some love by buying me a coffee (which I drink a lot of!). Just click on the link below.

Transcript

Tue, Feb 25, 2025 7:43PM • 36:41

SUMMARY KEYWORDS

Mississippi River, 1965 flood, Upper Mississippi, levees, snow melt, spring rains, flood stage, temporary dikes, sandbags, evacuations, flood damage, National Guard, federal disaster aid, flood plain zoning, flood walls.

SPEAKERS

Dean Klinkenberg

Dean Klinkenberg 00:00

Meanwhile, long time river dweller Ed Custer lost the fight to protect his house along Concord Street when the Mississippi moved it off its foundation and swept it away. Custer, who had lived 74 of his 75 years next to the Mississippi, swore he was finally done with the river. “Custer’s Last Stand is over. I fought long enough.” Welcome to the Mississippi Valley Traveler podcast. I’m Dean Klinkenberg, and I’ve been exploring the deep history and rich culture of the people and places along America’s greatest river, the Mississippi, since 2007. Join me as I go deep into the characters and places along the river, and occasionally wander into other stories from the Midwest and other rivers, read the episode show notes and get more information on the Mississippi at MississippiValleyTraveler.com Let’s get going. Welcome to Episode 57 of the Mississippi Valley Traveler podcast. Well, it’s beginning to feel a little bit like spring around here, which means flowers will soon be poking up from the ground, and we’ll be heading into that season where people look to the levees with concern. Some years the river gets higher than others, but it’s not always easy to forecast in late winter just how high the river is going to get weeks later. There are just too many variables at play. Winter snow cover certainly is one factor in that. But more often than not, spring rains make the biggest difference. Some years though, the timing of the snow melt and early rains comes together in a perfect storm. And that’s what happened in 1965 along the upper third of the Mississippi River, and that’s the subject of today’s episode. I’m going to tell you a few stories from that epic flood of 1965 which in many communities remains today. The high water mark, the worst flooding that many of those communities north of the Quad Cities have experienced. If you’re interested in flood and flood related issues, I suggest you go back and listen to episodes 25 and 26 where I talked with General Galloway about the epic flood of 1993 and also episode 30, where I talked with Nicholas Pinter about levees and what they really do and don’t do for us. Just a quick announcement before we get going on this episode. I am going to be in Rochester, Minnesota on Saturday, March 8. I’ll be speaking at the Rochester Public Library at 2pm talking about big rivers and and why we need to show them more love. So I’d love I’d love it if you’d come on out to Rochester and say hi and and listen to the presentation. As always show notes for this episode can be found at MississippiValleyTraveler.com/podcast. There, you’ll also find the complete list of all previous 56 episodes. You can go on a binge listening to previous topics that cover the gamut related to the Mississippi River. A shout out to all of you who are showing some love through Patreon. Your support keeps this podcast alive, makes me smile, makes me feel appreciated, all those good things. If you would like to become a part of that Patreon community, go to patreon.com/deanklinkenberg, and there you will find out how to do so. Patreon not your thing. Well, you can always buy me a coffee. I drink coffee every day. Caffeine is an important part of my life. So if you’d like to buy me a coffee, go to DeanKlinkenberg.com/podcast (editor’s note: go toMississippiValleyTraveler.com/podcast) , and from there you’ll see instructions on how to feed my caffeine habit, and now let’s get on with the episode. While folks along the lower Mississippi were forced to reckon with the power of the river in 1927 the people who lived along the upper Mississippi faced their epic struggle against high water in 1965. While there was no major flooding along the Mississippi’s first 300 miles, by mid April the Mississippi would essentially be in major flood stage from Fort Ripley, Minnesota to Hannibal, Missouri, a distance of over 650 miles. The Mississippi River begins as a modest stream that meanders its way for 450 miles through forests and plains flattened over 1000s of years by continental glaciers. At Minneapolis, the river flows through a narrow gorge before entering a deep and dramatic valley lined by tall limestone face bluffs. From Hastings, Minnesota to Cape Girardeau, Missouri, those bluffs confine the river to a flood plain that ranges from one to eight miles wide. When the Upper Mississippi over tops its channel, its waters just can’t go that far. It can still inflict plenty of hurt when it floods though. In 1965 the Upper Mississippi Basin experienced a perfect convergence of natural forces that created a historic river crest. A rapid melt of a thick snow cover, heavier than normal, rain and frozen ground. When all three of those happened at the same time, the Mississippi rose higher than it ever had in recorded history, and for many communities, higher than it has since. After an unusually wet September in 1964 the ground was deeply saturated and remained so through the fall. Nature played a big trick on people in the Upper Midwest in November by blanketing them with uncare uncharacteristic warmth early in the month, then smacking them down with a nasty cold wave a couple of weeks later. Dubuque, Iowa, for example, recorded a high temperature of 70 degrees on November 11, but shivered through a low of two degrees below zero just three weeks later. Many cities in the Upper Midwest set record low temperatures in November, and the bitterly cold air kept people bundled up through February. The first hints of trouble arrived with a warm up in late February, which melted some snow, but not the ground, when two inches of rain fell in early March across parts of southern Minnesota, the Cedar, Zumbro and Root Rivers whose waters all flow to the Mississippi, left their banks. The weather turned cold again, then a massive blizzard in mid March dumped up to 18 inches of snow on the northern plains states. The snow cover at St. Cloud piled three feet high in March, so high that drivers tied brightly colored pennants to their antenna, a signal that rose above the snow banks to alert other drivers to their presence. St. Cloud may have experienced more extreme weather than other communities, but March was wet and cold in many places. Minneapolis was warm enough for rain in early March, but Minneapolitans still had to dig out from 37 inches of snow during the month. Further south, major storms piled up snow in Iowa in early March and again in mid March. Des Moines, Iowa recorded the second coldest March on record. Lake Pepin, the widening of the Mississippi River just south of St Paul was a giant sheet of ice stretching three miles wide, 20 miles long and up to three feet thick. Because of the late, extreme cold, many smaller streams were totally frozen over by the end of the month. In late March, temperatures warmed quickly and often remained above freezing overnight, heavy rains fell in the first week of April, quickly melting much of the snow pack. With the ground still frozen, melting water ran unabated into the rivers. Smaller rivers rose first. As the ice cover broke up, chunks of ice clustered together into jams that blocked rivers and sent water overflowing banks. In a short time, half of the Crow River Watershed just west of Minneapolis was flooded. The Rum, Salk, Elk, Minnesota and St Croix Rivers also spilled out of their banks before merging with the Mississippi in northern Minnesota. Eight county roads washed out around Aitken. At Brainerd, a temporary dike six feet tall had been hastily erected to protect a water pumping station and an electric substation. An ice jam formed around the Mississippi River Bridge at St. Cloud, flooding areas north of downtown with five to six feet of water. At Elk River, the Mississippi cut across a horseshoe bend, flooding 26 houses. Water poured over Highway 10 and snow plows were brought in to break up ice piling up on the roadway. Some good news came from the small community of Dayton where its 450 residents successfully fought back high water from the Mississippi and Crow rivers when volunteers finished temporary dikes. By mid April, the smaller rivers of the Upper Midwest were falling back into their banks, but the crests were rolling down river and would threaten the Twin Cities and communities further south. By mid April, a few dozen families had evacuated low lying areas around Minneapolis. Flooding forced the closure of two sewage treatment plants in the Twin Cities. So untreated sewage flowed into the Mississippi River. Big chunks of ice clogged the river and crashed into bridge piers, which is generally not a good thing. Piers for the Plymouth Avenue and Broadway bridges were damaged. Worried city officials deployed 50 people to keep an eye on the integrity of all of the city’s bridges. The flood waters would eventually undercut a pier of the Stone Arch Bridge, an active rail bridge at that time, forcing expensive repairs once the flooding was over. In North Minneapolis, residents of North Mississippi Court watched nervously as the river crept closer to the community of 25 four unit buildings. Adults and children alike rallied to build a temporary barrier to protect their homes, a plywood wall that was held in place with piles of sandbags, nearly a third of the residents had already moved out by mid April. For those who stayed, “The worst part was the waiting,” one resident said. On April 14, Dan Hnath, a high school student and gymnast, got more attention than he had bargained for. He and a friend had been jumping on parts of the frozen river near Brooklyn center when a chunk of ice five feet wide and 10 feet long, broke free and quickly carried him into the middle of the river. Rather than panic Hnath “crouched surfboard style and nimbly rode the door sized flow past hundreds of horrified onlookers” a newspaper reported.The fun didn’t last, though, the ice glanced off of two bridge piers, but it remained intact, fortunately, when a man on shore tossed a rope in his direction, the rope turned out to be too short. A rescue squad soon showed up, that included a Navy helicopter and police but it was the fire department rescue boat that pulled up next to Hnath that succeeded in getting him off the ice back on land. He got a good scolding from rescuers and from his mother. He later admitted to feeling plenty scared, but as the next day was his 18th birthday, he said he intended to go back to the river to play around again. Well, at least he promised to stay off the ice. Downstream of Minneapolis, the evacuations continued with two dozen families moved out of Inver Grove Township and Mendota Heights. Residents of perennially flooded Lilydale began moving out in early April. The water reached the roofs of many homes, and the force of the current twisted buildings off their foundations. By mid April, 800 people had been evacuated from endangered parts of St. Paul. The city’s main train station, Union Depot, was closed because rail lines feeding it were under water. Holmen Field, St. Paul’s downtown airport disappeared under nearly eight feet of water and would remain closed for four weeks. A temporary flood wall went up along Shepard Drive. Not every business was interrupted by the flooding, though. In mid April, the Minnesota Senate approved a bill that would allow state institutions to serve oleo, a vegetable oil based butter substitute that we now know as margarine. That oleo prohibition in Minnesota dated all the way back to 1921. On April 14, President Lyndon Johnson stopped in St. Paul to inspect the flood damage. He surveyed the city as a cold drizzle fell, then left to a chorus of thunder and lightning. Earlier that morning, officials have blown up the clubhouse at the St. Paul Yacht Club because they were worried the building would break loose and float into boats and bridges down river. After three blasts of dynamite, the club caught on fire and burned to the water line and sank just down river of the boat club. The stubborn staff of the Golden Garter on Navy Island, the “Twin Cities only Banjo Band Saloon,” was finally forced to shut down as waters crept up toward the second floor of the Minnesota Boat Club, where the bar was located. The previous day, three musicians had played a few songs on the roof to let folks know the club was still open for business. The morning after the club closed, the Mississippi washed away a wall that had been protecting the building from the flooding river. The Mississippi peaked in St. Paul on April 16 at just over 26 feet, four feet higher than the previous record set in 1952 and a record that stands to this day. Concerned about the flow of disaster tourists, St. Paul granted the police the authority to arrest sightseers who interfered with flood fighting activities. Minnesota Governor Karl Rolvaag banned amateur photographers from flooded areas because officials worried they lacked the judgment to avoid taking risks while eagerly snapping pictures of the disaster as the high water rolled into the wider valley below St. Paul. The problems got bigger in South St. Paul. The city’s sewage treatment plant was knocked out of service and remained so for four weeks, and railroad tracks through the city were flooded. A three and a half mile temporary dike was built to protect the St. Paul Union Stockyards and meat packing plants. Units where 260 employees had been on strike for nearly a month. Meanwhile, long time river dweller Ed Custer lost the fight to protect his house along Concord Street when the Mississippi moved it off its foundation and swept it away. Custer, who had lived 74 of his 75 years next to the Mississippi, swore he was finally done with the river, “Custer’s Last Stand is over. I fought long enough.” The river also took 300 jars of canned fruits and pickles and his pet cat. He told reporters later, “I don’t know what I’ll do, but I’m through with the river.” 20 miles downriver at Hastings, the Army Corps of Engineers was scrambling to shield the control station at Lock and Dam #2. 100 volunteers worked in cold, wet weather to construct a temporary barrier to protect the sensitive electronics that kept the lock open with high winds added to the challenges. A Naval Reserve helicopter dropped life jackets for the volunteers to wear in case they were blown into the river nearby. Hastings resident Peter Mitzuk devised a creative method for protecting his house from the flood. He wrapped it in a sheet of plastic film. Five feet of river water surrounded his home, but the inside remained dry, except for some seepage that bubbled up from underneath. Another five miles downriver, low lying areas around Prescott, Wisconsin struggled against record crests on the St. Croix and Mississippi Rivers, which merged near downtown. The city’s sewage treatment plant had to be shut down, and officials closed U.S. Highway 10, a vital east-west route. Red Wing, at the upper end of Lake Pepin, also lost its sewage treatment plant. US Highway 63 was closed, so officials set up a ferry to temporarily move people and cars between Minnesota and Wisconsin. Further downriver at Lake City, 50 homes in the central point neighborhood were damaged by ice flows that rammed into the shore. For the residents of Wabasha at the lower end of Lake Pepin, the situation was growing tense. Roads into and out of town were flooded, and the city was surrounded by water. One newspaper reported, “The island of Wabasha, formerly a Minnesota city linked by dry land to the rest of the state, was about 1/3 water Friday.” 40 families had already been evacuated. Sandbags had been piled on its levee to raise it four feet. Worries shifted from the height of the river to the large chunks of ice coming out of Lake Pepin, the city had barely avoided disaster when an ice flow a quarter mile long and hundreds of feet wide crashed into woods north of the city, knocking down trees in the flood plain forest. If a flow that size had rammed into the city’s levee, much of Wabasha would have flooded. The closed highways complicated the delivery of medical care. Mrs. Willard Drysdale was scheduled for major surgery in Wabasha, but she needed infusion of a rare type of blood. Doctors at St Elizabeth Hospital requested the blood from the Red Cross in St. Paul, who then had to engage a creative delivery process to get the blood to Wabasha. A police car drove the packages of blood to Hastings where it was handed off to Norman Jacobson, who flew the blood to Wabasha in helicopter. Jacobson had trouble locating the landing site, though, so people on the ground waved him in the correct direction until he spotted a red flare marking his destination. Once on the ground, he handed off the blood to Sister Lucretia, who, “Ran habit flying in the wind to the hospital.” It took six hours to get the blood to the hospital, but the surgery went fine, and Mrs. Drysdale was recovering well the next day. For all of the challenges faced by people in the Twin Cities, in Waukesha, the risks were relatively minor. The places facing the greatest challenges were down river, and the city with the most to lose was Winona, Minnesota. The city was built in an area where Dakota Indians had lived, a place known as Wapasha’s Prairie. It’s flat, really flat. Without levees, the city would flood regularly. Winona was, as Harold Breisath, president of the city council, said, “Nothing but a cotton picking sand bar in the first place.” Hey, Dean Klinkenberg here, interrupting myself, just wanted to remind you that if you’d like to know more about the Mississippi River, check out my books. I write the Mississippi Valley Traveler guide books for people who want to get to know the Mississippi better. I also write the Frank Dodge mystery series that is set in places along the Mississippi. My newest book “The Wild Mississippi” goes deep into the world of Old Man River. Learn about the varied and complex ecosystem supported by the Mississippi, the plant and animal life that depends on them and where you can go to experience it all. Find any of these wherever books are sold. As the Mississippi rose in late March and early April, Winonians realized they were facing a much bigger threat than usual. In early April, the city organized an effort to add height to existing levees and to build a new dike around vulnerable areas. Unlike other cities that have relied on volunteers, Winona hired experienced contractors feeling a sense of urgency. Mayor Rudy Ellings told the press, “We haven’t even thought about the cost.” Gerry Modjeski, 24 years old at the time, and a foreman at his father’s plumbing company recalled, “All the contractors met at Winona Heating, and we laid out a plan and decided what dikes had to be fortified, what dikes had to be built new and began to construct all those areas with heavy equipment.” Within a week, the city had mobilized 20 bulldozers and 100 trucks to build an eight mile temporary levee that wound its way around the city. The stakes were high. If they couldn’t get a strong enough dike built, the river could flood three quarters of the city and the homes of 15,000 people. In 1965 Ken Morgan was 16 years old and obsessed with golf. When his high school was closed because of the flooding, he and many of his classmates got jobs fighting the flood. He got paid a buck and a half an hour, which was 25 cents higher than the minimum wage at the time. After the 15 minute training video, they were put right to work. He recalled later, “They’d bring in a pile of sand. You’d have one guy with a shovel and another guy holding the bag open. You’d throw two or three shovel fulls in the bag, and then someone else would carry it off and actually lay it down on the dike. It was a pretty good system. It was very well organized.” Ken Breukse, a sophomore at Winona State University, also worked on the front lines. He said we had a chain gang approach from filling the sandbags and then handling them along the dike. I don’t remember the exact number, but there were a lot of us. The city workers would line the dike with plastic, and we would place the sandbags on the plastic. The city workers told us that we were going to be the force that saved the city. Let me tell you, we all gave 125% the crews worked in 12 hour shifts under difficult conditions. It was loud from the constant parade of trucks coming and going. The air had a distinctive smell too, one Morgan recalled later. I can still smell that combination of wet burlap and diesel fumes. It’s a smell I haven’t smelled since, but I can almost relive that. And the people out on those front lines couldn’t escape the raging river. Morgan said we were just like a finger of sandbags out there in Prairie Island. I could look out on both sides of the dike and see water. We had no idea, really, just how fragile our safety really was. Another volunteer recalled it was pretty scary and a dangerous situation. The river was running wild, and just trying to get the plastic and sandbags in place was very dangerous. One misstep and you were gone. The river continued to rise. 100 families were forced to leave their homes north of town. On Prairie Island, rail traffic into the city was cut off. Sandbags were piled in front of doors and basement windows of downtown buildings. Pumps were moving 40,000 gallons of water a minute back into the Mississippi. High winds threatened to knock over parts of the temporary dike. As the river rose, engineers grew concerned that the increased water pressure might cause the storm sewers to explode. 1000 people were moved out of the high risk areas as a city worked on a risky plan to deal with the problem, to send divers into the sewers to plug them with inflatable rubber bags. Ray Beyers was one of those divers. At the time, he was 34 years old and worked as a glazier for Reinert Art Glass, but he’d been a diver when he served in the Navy. 40 years after the flooding, he described what his experience was like, “There’s rungs in there for sewer workers to climb down. I just walked right down, like going down a ladder, but it was a little awkward to get all that stuff on. The shoes weigh around 40 pounds. Then you have a belt that weighs 80 or 90 pounds. Last thing you want is to have too much air in there and you float to the top. That’s why the lead shoes, you crawl along like a crab on one foot and then one arm, then the other foot and then other arm, and you don’t know what you’re going to walk into. It was only about five or six feet across. There’s two or three or four openings. They knew which one was pointing toward the river, and we just had to go and make sure the thing was clean so there were no obstructions in there. We took a garden rake and cut it off, then they bent it so it fit in a big pipe. I put the rake in there and made sure it was clean. Then I took the bag and put it down in there, and then we filled it up with air, and that sealed it off. It was like filling up a car tire over about six blocks. As soon as you put that in there, they said the water quit rising.” Exploding sewers weren’t the only threats to the city. Volunteers placed logging pikes on the west side of the levee to deflect ice chunks. The river rose uncomfortably close to the top of the dikes, but a stroke of bad luck for folks on the east side of the Mississippi meant good fortune for Winonians. Gary Evans was a 24 year old sports reporter for the local newspaper during the flood. He was on Prairie Island that day, on April 16, Good Friday, when he witnessed a remarkable turn of events. He said, “While we’re standing on the Prairie Island dike, speculating about, are they going to pull the flood workers off? All of a sudden the water started. At first it seemed like an optical illusion, but all of a sudden you could see the water start to drop, and it dropped about 18 inches in what seemed like just a few minutes. I think in reality, it was more like an hour.” On the opposite shore, a berm supporting railroad tracks collapsed near the village of Bluff Siding, the Mississippi River pored through and spread out over 7500 acres of land in Wisconsin. Evans said that took significant pressure off the dikes, and probably is the reason the dike didn’t break. City officials in Winona organized non stop surveillance of their flood protection system to spy week spots and quickly repair them. The National Guard, Morgan said, had strung a kind of Battlefield phone system along Prairie Island every quarter mile to half a mile. They had a phone set up. They needed someone to man that phone so that if there was a problem, we could phone it. The Mississippi finally crested on April 19, the day after Easter, at 20.77 feet, three feet higher than the previous record, but three feet below the top of the temporary dike. Bruekse recalled “When the river had finally crested, the dike held and the city was saved. Let me tell you, we were all very happy.” The Mississippi would remain above flood stage for 24 days, but the levees held. It was an impressive effort. 1500 people worked feverishly to place 1.3 million sandbags. Carol Slattery was 22 years old when she volunteered with a Red Cross, she said, “I just remember how the whole community joined together and how people volunteered, whether it was resources or time.” Morgan recalled, “There was never any panic or sense of crisis. We were 100% confident this plan was going to work and we were going to beat the flood, and we did. It only struck me years later that I don’t know what our odds really were of having that be successful.” The flood flighting efforts cost the city $2.6 million but saved multiples of that in damages. For Ken Morgan, the long days filling and stacking sandbags proved to be a lucrative gig. He used the unexpected income to buy himself a set of high end golf clubs. Down toward the Gulf of Mexico, the water continued to roll, submerging sections of Wisconsin’s scenic highway 35, the Great River Road. By mid April, only one river bridge remained open in the 200 miles between La Crosse and Davenport, a bridge connecting Dubuque, Iowa with East Dubuque, Illinois. Charlie Hale, a photographer then with the Rochester Post-Bulletin, who worked dawn to dust during much of the flood, saw what he described as “Hundreds of homes and cabins along the river had been flooded. Some were slashed to kindling by wind whipped ice flows, and farmers had to use boats to feed their chickens.” In La Crosse, Wisconsin, five miles of levees were raised or built. Pumps moved water from storm sewers over dikes and into the river. 200 families in low lying areas were temporarily relocated. Water backed up the channel of the La Crosse River and cut off the two main roads that connected the north and south parts of the city. When a railroad dike collapsed, a major street disappeared under several feet of water that submerged cars in water to their headlights and forced 1200 people to evacuate Wisconsin. And Senator William Proxmire toured flooded areas and advised and advised residents that the best way to get aid was to “Complain, complain, complain.” Meanwhile, hopes dimmed that rescuers would locate Northern States Power employee, Roland Fischer, the 45 year old Fischer, had disappeared on Friday night when he set out in a boat to ferry employees from an isolated power station on French island. He never showed up. Witnesses last saw him in the boat floating without power as it approached a rail bridge further down river, 1000 residents of Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin had to leave their homes. 1/3 of the city was underwater. All roads into and out of Marquette, Iowa were flooded, and the town’s main street was covered with nearly four feet of water. The Mississippi crested four feet higher than the previous record at Dubuque, Iowa, and remained above flood stage for 28 days. The city built a temporary dike that ran three and a half miles thanks to the labor of 3500 volunteers who placed 400,000 sandbags.That temporary dike was a key reason their Mississippi River Bridge stayed open. At Clinton, Iowa folks successfully protected downtown with a mile long temporary dike, but businesses in the Lyons district, the north part of the city, weren’t as lucky. 50 businesses flooded across the river. Much of Fulton, Illinois, disappeared into the Mississippi as the river breached several levees, more than half of the city’s 3400 residents were forced out of their homes. People reacted to the hardships in different ways. Many fled their homes for emergency shelters. Others moved in temporarily with friends or family. 75 year old Harry Steele, known around town as “Silent Henry”, though, rode out the flood in a raft tied to a tree that floated above the single room shack where he lived. He refused all offers of help to evacuate from his home on Joyce’s island near Clinton, Iowa, where he had lived for at least 28 years. He told would be rescuers, “I wrote it out in ’52 and I’ll ride it out in ’65 there ain’t no man or officer going to take me off my island.” Incidentally, that was Steele’s last flood, he died in his cabin the following year. He had apparently died of a heart attack or a stroke. A couple weeks before his body was found, he was buried in a county cemetery, and sadly, officials were unable to find any next of kin to come to his burial. Residents of river towns fought the high water for another 200 miles south of Clinton all the way to Hannibal, Missouri. 12,000 people had to leave their homes in the Quad Cities, region of Iowa and Illinois. Homes and businesses in Muscatine, Iowa were flooded when a pump failed for just a few hours. A stack of 40,000 sandbags wasn’t enough to protect the business district of Keith, Illinois. Levee breaks in Illinois flooded 28,000 acres of Henderson County, just across the river from Burlington, Iowa. In the riverside town of Gulfport, roofs were the only visible sign of the city’s neighborhoods. At downtown Hannibal, stores lined their doors with sandbags and temporary walkways kept foot traffic dry so most, most stores managed to stay open. The river crested on April 16 at St. Paul. Over the next 12 days and 320 miles, the crest rolled down river and set records that still exist for river towns as far south as Fulton, Illinois, many tributaries also set records, notably the Minnesota River, all told, 19 people died in the flooding. Hundreds were injured, and 40,000 were forced from their homes. The Red Cross assisted 150,000 people, and over 3700 National Guard troops were deployed to fight the flood and help with cleanup. The flood caused some $200 million in damages in 1965, which is well over a billion dollars in today’s currency. The federal government declared 183 counties in five states eligible for federal disaster aid, most of them in Iowa and Minnesota. Damages from the 1965 flood were almost eight times greater than the next greatest flood, the flood of 1952. A difference that had little to do with the amount of water overflowing. One official told the press, “Perhaps the greatest consideration is the increased occupancy of flood plains, the tremendous property damage that results from major from major floods, points out the need for flood plain zoning.” After the flood of 1965 cities along the upper Mississippi got busy building flood walls and levees. Winona got a flood protection system that spanned 11 miles and took 20 years to build. Clinton constructed a tall levee between its downtown on the river. What didn’t happen, few communities made any effort to re examine the wisdom of building extensively in the flood plain. Well, I hope you enjoyed that story about the 1965 flood that is from my book ‘Mississippi River Mayhem.’ If you want to read more about floods and big floods and other pleasant topics, including plagues and murder etc, go run out and go buy yourself a copy of Mississippi River Mayhem. Available wherever books are sold. Of course, thanks for listening. If you enjoyed this episode, subscribe to the series on your favorite podcast app so you don’t miss out on future episodes. I offer the podcast for free, but when you support the show with a few bucks through Patreon you help keep the program going, just go to patreon.com/deanklinkenberg. If you want to know more about the Mississippi River, check out my books. I write the Mississippi Valley Traveler guide books for people who want to get to know the Mississippi better. I also write the Frank Dodge mystery series that’s set in places along the river. Find them wherever books are sold. The Mississippi Valley Traveler podcast is written and produced by me, Dean Klinkenberg, Original Music by Noah Fence. See you next time you.