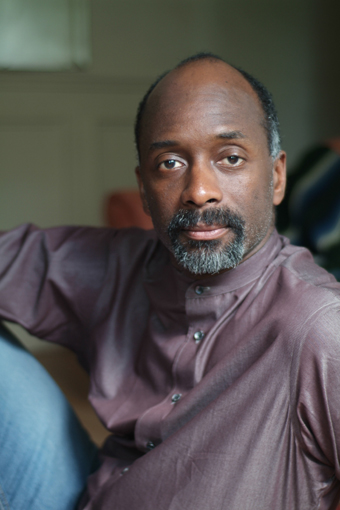

Eddy Harris is a brave man. In the 1980s, he bought a canoe and paddled the Mississippi on his own, a feat that is challenging for the most experienced canoeists, which he wasn’t. Before the trip Harris knew what a canoe looked like but had spent little time trying to paddle one. He started his trip in early fall at Lake Itasca, a chilly time of year to set out, and navigated the big river all the way to New Orleans. He recounts the story of his trip in his memoir Mississippi Solo, published in 1988, one of the finest books about the joint expedition of exploring the Mississippi River and oneself.

Eddy Harris is a brave man. In the 1980s, he bought a canoe and paddled the Mississippi on his own, a feat that is challenging for the most experienced canoeists, which he wasn’t. Before the trip Harris knew what a canoe looked like but had spent little time trying to paddle one. He started his trip in early fall at Lake Itasca, a chilly time of year to set out, and navigated the big river all the way to New Orleans. He recounts the story of his trip in his memoir Mississippi Solo, published in 1988, one of the finest books about the joint expedition of exploring the Mississippi River and oneself.

Now, at age 60, he wants to do it again, but this time with a camera crew to help him document his experiences as well as the stories of the river. He is raising money for the project through Kickstarter.

UPDATE (10/7/2013): Eddy has shifted his fundraising site to Indiegogo. You can find it here.

UPDATE (December 2017): The film, River to the Heart, is complete and showing in select theaters around the U.S.

We discussed his previous work and new project via email.

Before your first canoe trip, what was your relationship with the Mississippi River?

I’ve always had a relationship with the Mississippi. I grew up in St Louis, and my father worked downtown. As we had only one car, my mother would drop him off and in those years before I started school, I would be with them. And my mother, in love with St Louis and so proud to have been the sixth generation in her family born in St. Louis, in love with the river full of stories about St. Louis and its history, we would invariably take a tour of the city before heading home. That tour always included a drive along the river.

Even after I started school we would drive down to the river just to sit and look at it — and to watch the Arch going up. In fact, we were in the crowd the day the final piece was wedged into place.

The river — and all those excursions on it and all those rumors about its dangers (not all merely rumors) and about its hypnotic spells — has always been a huge part of my imagination and literary life. Huck Finn, Life on the Mississippi. Riding upriver in winter to watch the bald eagles.

How did that trip change your relationship with the river?

The trip brought it all home, brought it all together for me. The fear, the adventure, the beauty. Even the outdoorsy aspects. I wasn’t a camper before I took that trip, wasn’t even a canoeist. Had been in a canoe maybe a handful of times, camping even fewer. But since the trip I can’t get enough of being out and sleeping under the stars. My whole relationship to nature changed — from being a city boy to loving the solitude and splendor of being out in nature, whether canoeing or camping or hiking. I still don’t like mosquitoes much, but I earned a finer appreciation for the natural world — just by being in it for such a concentrated time.

How did it change how you see yourself?

The biggest change I noticed once I got off the river was — I don’t want to call it swagger or even confidence; I’ve always had plenty of self-confidence. But there was something. Maybe the certainty afterwards that I could do anything I set my mind to. I had been writing at the time for about eight years with no visible success. Naturally, doubt can creep in. After the river trip — even though it would take another three years before a book of mine was published (Mississippi Solo), I had no doubt that I had the tenacity to stick it out and make it happen. And that I attribute directly to facing myself on the river and the daunting task of doing the river. I felt — if you can do that, man, you can do anything!

The trip might also have altered my attitudes about race — but I don’t think so. I’ve always looked at the brighter side of things and always expect the best of people. My experiences have borne this out time and again. So when I did encounter an incident or two that might have had racial undertones, I tried to see them differently. In any case, by the end of the journey I felt really in touch with and in tune with this middle part of the country. And the South was no longer such a scary place for me.

As an African American guy, do you think you see or experience the river differently than folks from other backgrounds?

I’m sure I see the river and that journey differently than someone else, someone white, might have lived it. Race, as unimportant as it may be in my personal psyche, is perceived in reality as something fairly fixed. The trepidations I carried might not have been what someone else might have been haunted by. My uncle Robert at the beginning of Mississippi Solo says: “You’re going from where there ain’t no black folks to where they still don’t like us much.” It was something at least to be concerned about. The horrible stories of what can happen to young blacks out in the middle of nowhere — or not necessarily the middle of nowhere — but can and has happened historically to blacks out there alone can fill you with trepidations beyond the lions and tigers and bears that someone not black might be troubled by. And in the end, when you arrive alive and in one piece having been sheltered and helped by all manner of people all along the way and you measure that against the incident or two which may or may not have been racial in nature and you just have to start questioning. Not that the horrors aren’t real, but that they might be the exceptions and not the rules. Which I happen to think is the case.

You’ve written other books, have other projects; what is it that has pulled you back to travel the river again?

I’ve always felt I wanted to do the river again. The time I did it I had no idea what I was doing. Now, I think I do and I would like to see if that’s true, if I will approach the river differently. Not with less fear or less respect. In fact when I was filming the little clip for the documentary I hope to make, I was quite fearful when I stepped into the canoe and paddled out to shoot. “Quite fearful.” In fact, I was petrified and if not for the fact that the cameraman was waiting for me across the river, I think I might have backed out. But once in the canoe it felt like meeting an old friend. It was great. So I want to rekindle that feeling. And I want to test myself again, of course. But I also want to see if the country has evolved, if the election of a black man to the White House actually means something.

Of course it means something; but what?

Putting myself back in the canoe, back on the river, exposed and alone — even though with a camera crew (I hope) — will answer some of those questions.

But all that aside, the first time down was such a powerful slice of my life that I want to see what will be different in recapturing it — or trying to. Stepping into the same river twice, as it were.

Tell me about your Kickstarter project.

The aim this time is to share this experience with a much wider audience. I hope to document this trip as a film — partly to share the experience with many more people, partly to explore the river differently than you can in written form.

So I’ve gotten a good crew together, a few people who are as enthralled by the river and committed to the project as I am, and we’re hoping to descend the river and tell its story. My story too, but the story of the river. My tagline is: if the river could talk, this is the story it would tell.

In fact the river does talk. We hardly listen and hardy hear. But with this film I hope to give voice to the river, in a way. That’s the aim, anyway. To look at the river in way that’s not quite been done before.

But fundraising is not easy. So far nothing along the normal routes has worked. So I launched a crowd-funding campaign in the hopes that lots and lots of people will feel the project is worthwhile and will contribute to its funding and help to get it done. We offered lots of great rewards to give people an added incentive, but the real impetus should come from wanting to see this project get afloat.

Not an easy task, asking for so much money in such a short time span. Not an easy task even with more time available. But I’ve only got a year. We need to be on the water some time next year — late summer, early autumn — for this to work. So the appeal goes out for contributors and for contributors to spread the word.

You can learn more about the project and contribute here.