Some songs, for whatever reason, catch on quickly and stick around long enough to spawn generations of copies. Catfish Blues is one of those songs; with at least 200 recorded versions (according to the Encyclopedia of the Blues) it has a genealogy that rivals Brigham Young, just with fewer first cousin marriages. My extensive internet research on Catfish Blues led in some surprising directions.

According to Wikipedia, Catfish Blues is: “a song about a Siluriformes or ictalurus punctatus (it is not clear from the song which species is referenced) that suffers from clinical depression. Catfish, as the fish is commonly known, live in both fresh and salt water habitats. The lyrics indicate that the catfish is ‘swimming to the sea.’ It is uncommon for a fresh water catfish to survive in a salt water environment, so perhaps this line references a suicidal wish on the part of the protagonist. Clinical depression and suicidal ideation are difficult to measure in catfish, so prevalence rates are not known.”

That didn’t sound quite right, so I kept digging and came across another internet expert who indicated that the song may have its origin in two simple lines from Jim Jackson’s Kansas City Blues, Part 3, which Jackson recorded for Vocalion in 1928. The third verse goes:

“I wished I was a catfish, swimming down in the sea;

I’d have some good woman, fishing after me

Then I’d move to Kansas City….”

Jackson grew up just south of Memphis in the Mississippi Delta town of Hernando and later moved to Memphis proper. His geography was a little off, because if he was really a catfish heading out to sea, his destination from Memphis wouldn’t be Kansas City, but, hey, there are worse places to travel to, whether or not you’re a catfish. So we’ll give Jackson credit for recording the song that first used the familiar lines. We’ll call him the grandfather of Catfish Blues.

The first song to be called Catfish Blues wasn’t recorded until 13 years later (it takes those children some time to grow up) when Robert Petway did so in Chicago, although the song itself was not unknown. It was a mainstay in Tommy McClennan’s repertoire when he was performing in clubs around Greenwood, Mississippi in the 1930s. Petway and McClennan were friends and played a number of shows together, so perhaps Petway picked up the tune during that time.

When Petway recorded the song in March 1941, McClennan had already been recording songs in Chicago for two years and probably invited Petway to Chicago to record. Petway’s version was not a ripoff of McClennan’s by any means. According to the internet, Petway’s version played at a faster tempo, did not use a slide, and included new verses.

Petway lyrics are below; notice that his catfish has a better sense of direction:

“Well, I laid down, down last night

Well, I tried to take my rest

Notion struck me last night

B’lieve I b’lieve take your stroll out, out west

Take your stroll out, out west

Take your stroll out, out west

Take a stroll out west

Take a stroll out west

Well, if I was a catfish, mama

I said, swimmin’ deep down in deep blue sea

Have these girls now, sweet mama

Sittin’ out, sittin’ out, folks, for poor me,

Sittin’ out, folks, for poor me,

Sittin’ out, folks, for poor me,

Sittin’ out, folks, for me,

Sittin’ out, folks, for me,

Sittin’ out, folks, for me,

Well I went down, yes!

Down to the church house, yes!

Well, I was called on me to pray

Fell on my knees, now

Mama, I didn’t know one

Not a word to, who say

Not a word to, who say

Not a word to, who

Not a word to, who

Not a word to say

Not a word to say

Not a word to say

Play ‘em man, play ‘em a long time

I’m gonna write, write me a letter, baby

I’m gonna write it just to see

See if my baby, my baby, do she think of

Little old thing, on po’ me

Little old thing, on po’ me

Little old thing, on po’ me

Little old thing for me

Little old thing for me

H’oh, little thing for me.”

Just a few months later, McClennan recorded his own version of the song but called it Deep Blue Sea Blues. In his version, the catfish is a bullfrog (another hottie!) and only the second and third verses are essentially the same as Petway’s.

Other than the 16 songs Petway recorded in Chicago from 1941 to 1942, his life has been a total mystery. He left virtually no paper trail, no birth or death records, little to tell anyone who he was and what kind of life he had.

Petway’s version had many cousins in the ensuring years, some with a slow tempo, some speeded up. What they shared in common was a universal male conceit: believing you are hotter than you really are. The singer believes women will find him irresistible because he’s a fat, bottom-feeding slithering beast with whiskers? A trout maybe—now that’s an attractive fish— but not a catfish, unless it’s being chased to the fryer.

In 1950 McKinley Morganfield, better known as Muddy Waters, recorded a version of the song with several new verses and an electric guitar. He called his version Rollin’ Stone, a title that was later co-opted by a magazine and a British rock band (many of whom resemble catfish).

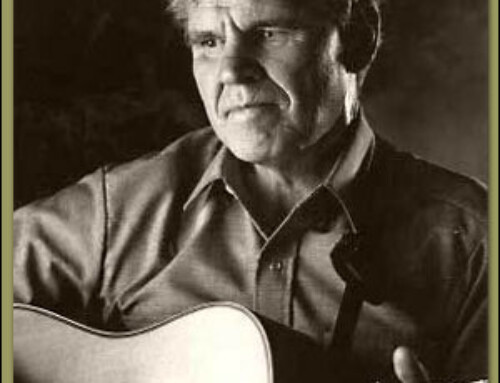

Muddy Waters:

His lyrics went like this:

“Well, I wish I was a catfish

Swimmin’ in a oh, deep blue sea

I would have all you good lookin’ women,

Fishin, fishin after me

Sure ‘nough, a-after me

Sure ‘nough, a-after me

Oh ‘nough, oh ‘nough, sure ‘nough

I went to my baby’s house

And I sit down oh, on her steps.

She said, “Now, come on in now, Muddy

You know, my husband just now left

Sure ‘nough, he just now left

Sure ‘nough, he just now left”

Sure ‘nough, oh well, oh well

Well my mother told my father,

Just before I was born

“I gota boy child’s comin,

He’s gonna be, he’s gonna be a rollin stone,

Sure ‘nough, he’s a rollin stone

Sure ‘nough, he’s a rollin stone

Oh well he’s a, oh well he’s a, oh well he’s a

Well, I feel, yes, I feel

Feel that I could lay down oh, time ain’t long

I’m gonna catch the first thing smoking,

Back, back down the road I’m goin

Back down the road I’m goin

Back down the road I’m goin

Sure ‘nough back, sure ‘nough back.”

So Muddy’s catfish is an adulterous wanderer. Where do you go from there?

How about getting even more electric courtesy of Jimi Hendrix? He recorded his own take on Catfish Blues in 1968, referencing Muddy Water’s lyrics in the first two verses then adding two of his own. Instead of being adulterous, Hendrix’s catfish was just horny and visiting his girlfriend. If you listen to Hendrix’s Voodoo Chile after Catfish Blues (this is starting to sound like a Texas buffet), you will hear some obvious crossover between the two songs, so we’ll call Voodoo Chile a second cousin of Catfish Blues. If you want to take it even further, the internet told me that Voodoo Child, one of Hendrix’s most influential songs, was just one more small step away from Voodoo Chile, so maybe it’s a second cousin once removed from Catfish Blues.

The list just goes on from here, with dozens of versions. Most use the first one or two verses then add their own, like this 1951 version from John Lee Hooker.

But wait; there’s more. Canned Heat recorded a fun version (I think we’re into grandchildren by now) in 1967.

Let’s not forget the 1999 collaboration between Taj Mahal and Toumani Diabate, adding a layer of Malian influence to the tune, with a reference to the lyrics of Jimi Hendrix. (I couldn’t find a good version of this on YouTube, so just listen to the version on the CD Kulanjan.)

Then there’s the 2002 version by Gov’t Mule, the southern rock band that included some members from the Allman Brothers Band.

And what does this have to do with the Mississippi River? The song seems to have emerged primarily from the Mississippi Delta, and it talks about catfish and there are lots of those in the Mississippi River. That’s good enough for me.

These songs also do a pretty good job of showing the progression from acoustic blues to the rock and roll of today. Anyone know of any hip hop or punk versions of Catfish Blues? That would help complete the line. I can’t wait to find out what the great-grandchildren are like.

I wonder, after listening to all these songs, could this happen today, in the brave new world of hypervigilant copyright enforcement? Probably not. I don’t think many artists today would bother with the legal and financial hurdles imposed by current laws, and, in the bigger picture, I don’t see how that’s a good thing.

Have I missed your favorite version? Let me know.

For more about this song and the artists involved, check out Max Haymes’s article from 2004.

© Dean Klinkenberg, 2011