People in North America have been getting around in canoes for thousands of years. The basic design was so perfectly engineered that we’re still using it today. In this episode, I talk with Mark Neuzil, who co-wrote “Canoes: A Natural History in North America” with Norman Sims. We talk about the basic design, variations in materials used to build them from traditional bark canoes and dugouts to modern composites. We cover the ways canoes were engineered for specific purposes, and the transition from canoes as transportation to canoeing for fun. Mark shares a couple of standout memories from canoe trips he’s taken, and in the Mississippi Minute, I share a couple of my own. Paddles up! We’re all about canoes in this episode!

Show Notes

Canoes: A Natural History in North America

Support the Show

If you are enjoying the podcast, please consider showing your support by making a one-time contribution or by supporting as a regular contributor through Patreon. Every dollar you contribute makes it possible for me to continue sharing stories about America’s Greatest River.

Don’t want to deal with Patreon? No worries. You can show some love by buying me a coffee (which I drink a lot of!). Just click on the link below.

Transcript

SUMMARY KEYWORDS

canoe, boats, birch bark, tree, paddle, river, built, materials, people, years, dugout, needed, north america, bark, lake, design, sail, mississippi, book, water

SPEAKERS

Dean Klinkenberg, Mark Neuzil

Mark Neuzil 00:00

The safest thing to say is that canoes reach their most advanced form in North America and the highest form of engineering in North America based on skills of the builders. They’re designed with the materials available.

Dean Klinkenberg 00:32

Welcome to the Mississippi Valley Traveler podcast, I’m Dean Klinkenberg, and I’ve been exploring the deep history and rich culture of the people in places along America’s greatest river, the Mississippi since 2007. Join me as I go deep into the characters and places along the river and occasionally wander into other stories from the Midwest and other rivers. Read the episode show notes and get more information on the Mississippi at MississippiValleyTraveler.com. Let’s get going.

Dean Klinkenberg 01:05

Welcome to Episode 22 of the Mississippi Valley Traveler podcast. I’ve got a fun conversation for you today, have a nice chat with Mark Neuzil, who is co-author of “Canoes: A Natural History in North America,” which he wrote with Norman Sims. It’s a beautiful book, a tome, a classic coffee table book, richly illustrated, great storytelling, very well written account of the history of this boat we take for granted that had its own sort of trajectory in North America. In this episode, we talk about the history of the canoe in North America and get into topics around canoe design and construction, and he’ll even throw out a few tips you can use if you’d like to build your own. We’ll discuss the two basic types of canoes in North America, bark and dugouts. And we’ll get into variations in canoe design that were engineered for different tasks. We also talked about the ways canoes were often dressed up with ornamental touches, which were unique to a tribe or a person. We’ll then get into a little discussion of the role of canoes in the fur trade, fairly brief discussion about that, then transition into recreational paddling and the growing list of options for materials we use to build a canoe today. And then we’ll finish with a couple of stories from Mark about memorable moments on canoe trips that he’s taken. As always, thanks to my Patreon supporters, Your support makes this podcast possible. If you want to join the community, go to patreon.com/DeanKlinkenberg and you can pledge there. If that’s not your thing, you can always buy me a coffee. Wanna know how to do that? Go to MississippiValleyTraveler.com/podcast and there’ll be a link you can follow there to buy me a coffee and feed my caffeine habit, which would be much appreciated. And now, let’s get on to the interview.

Dean Klinkenberg 03:12

Mark Neuzil is a journalist and journalism educator who is Chair of the Department of Emerging Media at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minnesota. He’s the author, co-author or editor of eight books and is a frequent writer and speaker on environmental issues. His book written with Norman Sims, “Canoes: A Natural History in North America,” was published by the University of Minnesota Press. Welcome to the Mississippi Valley Traveler podcast, Mark.

Mark Neuzil 03:39

Thanks, Dean. I’m glad to be here.

Dean Klinkenberg 03:42

Well, it’s a pleasure to talk with you today. I I’m such a big fan of your book, “Canoes A Natural History. It’s an absolutely gorgeous book for one thing, richly illustrated. I love the depth of storytelling and descriptions of how canoes were built and how people use them. How, what was your connection with canoes before you wrote this book?

Mark Neuzil 04:04

Well, it’s a lifetime in canoes, that was the start. Norm and I had similar experiences. We’re both from the Midwest. Norm passed away last year but we’re both from the Midwest. He’s from Illinois, and I was from Iowa. We grew up in canoes. I think I was introduced to a canoe when I was probably about 10 or 11 years old by my father who purchased one of the early fiberglass canoes in the late 1960s. He’s an early adopter kind of guy so when he saw the new materials for canoes, he jumped on it right away. And we lived close to a lake and close to the Iowa River. So, you know, summers and evenings after school were spent in a canoe fishing, canoeing, swimming, whatever it might be. And it just it stuck you know at all those years later it stuck with me.

Dean Klinkenberg 04:58

So you as I understand it, you still take a lot of canoe trips. You’re still out in canoes pretty regularly these days and have been for most of your adult life.

Mark Neuzil 05:08

Correct. I usually try to do three or four trips to the Boundary Waters Canoe Area wilderness in northern Minnesota or the Quetico National Park in Canada, although that’s, of course been closed the last few years, but the BWCA trips are a big part of my life. I take my family along at least once a year. I go with a group of friends at least once a year, try to get up there, smaller groups or solo as much as I can. And these are, you know, shorter trips, canoe camping trips that would be 5, 6, 7 days across across that wilderness.

Dean Klinkenberg 05:46

Yeah, it’s yeah, I’m a little envious that you live close enough to be able to take advantage of those opportunities to go to places that are still undeveloped, like the Boundary Waters and Quetico. Let me ask this, like, what, what actually, what defines a canoe, right? How is a canoe different from other boats?

Mark Neuzil 06:07

Well, it’s long and skinny. Usually, it’s open decked. That is to say it has no deck or just a very, very short deck, and it’s propelled with the, with the occupants facing forward with paddles rather than oars. So the paddles, of course, are not fixed to the gunwales, where oars are fixed to the gunwales in oarlocks. So when we think about a canoe, we think about a long, narrow, lightweight boat without decks, propelled by paddles with the paddlers facing forward. That’s the basic definition. You might know the follow up question, of course, is: How does the canoe differ from a kayak? Which is a common question. The kayak has a deck and the canoe does not. A kayak is usually paddled with a double bladed paddle, whereas a canoe is usually paddle with a single bladed paddle, although I use a double bladed one when I’m by myself, as do many, many others too. But the big difference is usually the presence of a deck and how low you sit in the water, how much water line and how much draft the boats have.

Dean Klinkenberg 07:21

And canoes have a very long history in North America. Can you just describe a bit how far back we think people have been building and using canoes in North America?

Mark Neuzil 07:32

Well, thousands of years, for sure. Carbon fiber dating, or sorry. Carbon, carbon fiber boats… I have some carbon repair to do later today, so it’s on my mind, carbon fiber boats are new. Carbon dating takes us way back thousands of years to the dugout boats that have been discovered in places like New Orleans, Lakeland, Florida and elsewhere. You know, 5000 years is probably a decent estimate. And it could be thousands of years before that. With these types of dugout boats, those boats will survive being buried in the muck in the bottom of a lake, you know, without the oxygenation that happens to destroy the wood. And we’ve seen some of those resurrected all over the country in the last few years. So I’m gonna guess, you know, 5000 years minimum but could be closer to 10?

Dean Klinkenberg 08:30

Are they unique to North America? Are there canoes in other parts of the world?

Mark Neuzil 08:36

Yes, and no, they were most well developed in North America, that we can say for certain. But we could also see boats that look a lot like canoes in places like Siberia. And of course, the South Sea Islands. There’s distinct differences between, between all those boats, which are kind of highly technical, but I think the safest thing to say is that canoes reached their most advanced form in North America and the highest form of engineering in North America based on skills of the builders, their design and the materials available.

Dean Klinkenberg 09:09

Was there something unique about North America that made this the epicenter of canoe technology then?

Mark Neuzil 09:17

Well, I think it was a combination of things. First of all, the indigenous tribes that lived in what became Canada and the United States, needed boats to travel because it’s a water based culture, especially in Canada, of course, but northern Minnesota, Wisconsin, those places in the northeast United States. It’s a water based culture and you had to get around via some sort of watercraft that was primarily in that region. And then secondly was the availability of the materials and you needed the proper kinds of wood to be able to build boats and have them last and be seaworthy, and the birch bark tree was probably, is key to that and that’s the region where the boats became sort of their peak of development. In the areas where the birch bark trees weren’t available, when you start to get farther south or farther to the Midwest, you’ve got dugout canoes, which are a lot harder to handle, a lot more heavy, somewhat more difficult to build, depending on how you how you look at it, if you have Stone Age tools, and just just a little bit harder to manage in terms of portaging and so forth. They’re really really hard to portage, as a matter of fact, so you want to, you want something light and fast and easy to fix if it breaks and and that’s what the birch bark gave you.

Dean Klinkenberg 10:38

Well, let’s let’s get into those a little bit more then. I am lucky enough to travel along, you know, the Mississippi in various places and I don’t imagine birch bark canoes, aside from the fact there aren’t birch trees very far south, birch bark canoes might be a little less ideal on the big open waters of the lower Mississippi, whereas the dugout canoes would be really hard to manage from you know, Itasca State Park, to Bemidji, for example. So the birch bark canoes, let’s kind of start there. What are the basics for how those boats were built, what materials were involved in construction.

Mark Neuzil 11:14

So a basic birch bark canoe needs a tree that became known as a canoe birch, paper birch. And one of the key things to note, Dean, in these these types of constructions is the the reason the birch tree bark works so well is that the grain of the wood runs differently than how we normally think of the grain of the wood in a, in hardwood tree. We think of an oak tree or an elm tree, the grain runs vertically, with the trunk of the tree up and down towards the sky where in a birch tree it’s, it’s a circumference situation. So the bark, the grain in the bark circles around the tree rather than running up and down. Well that makes the bark, in part, a lot more flexible. And it’s the flexibility that allows it to be bent into shape and crafted into shape with boiling water and so forth and the structure to, to give it that nice beautiful silhouette that we’ve come to know as the canoe. Other barks were used but not as not as well. Elm bark was probably the second most popular bark to be used. But you can tell him a canoe made from elm bark, and a canoe made from birch bark in about two seconds. It just doesn’t fold up as nicely because of the way the grain runs and the inflexibility of the bark. But the birch trees proved proved perfect for this. And of course, they were also used for baskets and teepees and, and footwear and a number of other products as well because of their because of their utility. But the canoe itself became kind of the pinnacle of the construction with the use of that particular tree bark. And then in addition to birch, you needed, you need to have thwarts, you needed a gunwale, you needed flooring and ribs, perhaps a deck. And in those cases, you almost always got cedar, which is a really light, but also waterproof wood that has a lot of oil in it, and also is readily available. So birch trees up in my part of the world are all over the place. Cedar trees are all over the place. So the ribs tended to be made of cedar. Also very flexible, very light. And then sometimes the gunwales are cedar, sometimes the gunwales are spruce. It kind of varies from location in whichever particular tribe is making the boat. You can see variations there and things like the deck. And then tying it all together is the other, the other issue, and you needed something that, this is, of course, before nails or tacks, and needed something to rope it all together. And so that tended to be the roots of a black spruce tree. And they’re all over up here as well. So you’ve got, the cool thing about the black spruce is the roots are very shallow. So once you find a tree and you find a root that’s about the diameter of your little finger, you can start to pull on it and it probably won’t be more than about six inches below the surface of the ground. So if it’s, if it’s loose soil, you can pull up 40, 50, 60 feet of it pretty easily. And then you’ve got a rope. Now the issue with tying it onto your canoe and tying your, let’s say, tying your gunwales to the, to the hall is that you’ve got a rope but it’s completely round. And if you want it really tight, you need one side that’s flat and you need the flat side, if you can kind of envision the flat side and being the downside, so to speak. That’s against the hull and the gunwale to make it as tight as it can be. So you had to take that route, maybe 60 feet, about the diameter of your little finger and split it right down the middle in half. And that’s hard. I’m just here to tell you that that’s a very hard thing to do to keep that knife straight and, and for 60 feet, because if you slip, all of a sudden you’ve got 50 feet, and then you’ve got 45 feet, and you’re starting over again real quick. So black spruce would be the, would be the, the tree that ties it all together, you could use tamarack, if you needed to, and there’s some others barks, or some other roots that would work as well. And then you need to make the glue, so to speak, the pitch that holds it together. And this is the stuff people when you think of birch bark canoes, you see the black stripes, right? It’s a white, usually the boats are white with black stripes. And by the way, that’s that’s a separate issue that we’ll get into. But the pitch is usually a secret formula that natives discovered that has usually bear fat. And then sap from that black spruce tree where they found the where they found the roots, and then usually a little charcoal is mixed in to, to give it that black color. So when you cook it long enough, it comes into the consistency kind of like the old bubble gum that we used to chew as kids, the big pink squares, you know, Bazooka Joe kind of gum, after your workout it for a half hour with your jaw. It’s that kind of consistency where you can stretch it out and smear it against the seam and then it’ll harden, and be pretty waterproof, really, you’re gonna get some some leakage, but it’s pretty waterproof. And the beauty of it is, if you need to stop and fix a leak, you just pull your boat over and look for a tree. And, you know, or maybe you’ve got a little cup of it in the bottle anyway, but you can patch it pretty quickly, with some with some sap and maybe a little animal fat.

Dean Klinkenberg 16:53

So there were several obvious advantages for the birch bark canoes. They were light, you know, for those frequent portages. They weren’t so cumbersome to move from, you know, across land when you needed to portage. They were fairly, you know, the materials were readily available to build them. They were abundant in those areas. And they could be fixed on the fly, which you know, they are kind of vulnerable, if you hit a rock, you know, you’re probably going to be doing a repair pretty soon after that, right? So those are pretty cool. They’re, they’re that, that’s the basic design. Weren’t there are also some variations in the engineering for birch bark canoes depending upon how they would be used.

Mark Neuzil 17:35

Correct. And it varied from tribe to tribe. And usually that meant region of the of the continent to region on the continent, and what they were used for. So, for example, an ocean going canoe, like in the Pacific Northwest would have been, would be a dugout made out of cedar. And that would be 22 to 30 feet long or longer and hold maybe a dozen paddlers but have very high, you know, stem and stern, would be high for big waves and the gunwales would be high, usually would have seats for paddlers in that kind of circumstance, because they would be going out going fishing or going spearing for seals and things like that. Whereas a canoe made for collecting wild rice in northern Wisconsin is going to be a very different design altogether. It’s going to be long and not quite so narrow, but probably without seats, and then have a relatively flat hull, a wide flat hull to hold the rice as you paddle through rice bed, rice beds and knock the wild rice off into the bottom of your canoe. So those boats are going to look very different. And the other differences that would be obvious would be boats with a high rocker. This is like the stem and the stern that are curved upwards, more like in a banana shape. Those are going to be boats built for fast rivers where you can turn on a dime, and spin the boat around in a hurry if you have to. Whereas other boats that are made for lakes won’t have those high rockers, there’ll be, the keel of the boat will be touching the water at a longer distance because they don’t have to turn on a dime necessarily. They need more, they need more stability in other ways. So it depends on the tribe. It depends on the uses that the tribe put them to. And then the materials that they were that they were made with as well.

Dean Klinkenberg 19:39

That was one of the things I never really thought about until I read your book was in the traditional birch bark canoes, there were no seats, right? So you basically, you’d be kneeling I guess as you paddled?

Mark Neuzil 19:50

Correct the the indigenous people tended to kneel although they also stood depending on the, on the need. But kneeling was the more traditional way. And it really wasn’t until the late 19th century, I want to say, if you look at some of the early boats built by white settlers in the mid-19th century in Canada, where the process of sort of building the boats with, by white settlers, instead of the tribes started to happen, they mimic the native designs and the first boats that the whites built also had no seat, had no seats. But pretty soon, as boats become less of a utilitarian vehicle and more for sport, you found, you found seats being used for people who like to fish, for example, or recreational use seats have started to be added by by the white builders. And, and then that’s, that’s really one of only two sort of changes in the, in the boat’s design. One of the things that Norm and I say in the book that we’re pretty confident of is that there are only two artifacts that Native American builders built that were unimproved upon by white settlement. In other words, they were perfectly engineered by the time Europeans got here. One was the canoe. There was really no improvement on the basic engineering of the boat. It’s the same boat now as it was 5000 years ago. And the other was the snowshoe, which the Europeans were not familiar with either. So those were engineered to kind of their pinnacle design and remain that way. Now, materials change, of course, the addition of seats, you could add that the addition of a sail occasionally would be part of that as well. Sails weren’t known to, to the North Americans either, then were brought by Europeans but, but weren’t very much in wide use either. They have tended to be kind of a small niche.

Dean Klinkenberg 21:53

Right sails on a canoe tend to be not very practical on rivers that bend and twist a lot. So you catch the wind for a minute, and then it’s gone.

Mark Neuzil 22:01

And it wouldn’t be my choice of travel. And the sails that I’ve seen on canoes, and you don’t, they’re not made for sails anymore, of course, but you can see some antique boats out that still have masts and a step and so forth. But they tend to have too much sail area in them, in a real sail, a real sailor who’s experienced will look at a canoe sail and go that’s way too much sail. You’re gonna dump it and you almost always do. Well, we looked at that, we looked at evidence of canoe races from the Canada and the US. And then late 19th century they had sailboat canoe race, you know, canoe races based on sails and the winning boat would tip over six times. I mean, it was just, it was, it was not sustainable.

Dean Klinkenberg 22:51

That’s a pretty low bar than for winning a race that you’re tipping over six times.

Mark Neuzil 22:56

All right. Well, that’s a person that has too much sail or just doesn’t, probably isn’t very good at it.

Dean Klinkenberg 23:01

Right. So what’s the Rob Roy? Was that one of the canoes that had a sail on it?

Mark Neuzil 23:06

Correct. The original Rob Roy by John McGregor was, looks to us probably more like a kayak because it had a deck. It’s probably 10 to 12 feet long. Some of them were, they were several rubberized, but the one I’ve seen in the museum, in one of the museums was was short, has a deck, but it also has a mast for sail and a step and it was for one person. McGregor went alone. And he stored his stuff underneath the deck to keep it dry, of course, and that sort of worked. But remember, he sailed 1000 miles and paddled, mostly paddled, really, but he did put the sail up occasionally across Europe and elsewhere, but the design was transferred to the US and and I found some popularity although in the northeastern United States, you saw some Rob Roy people like Nes Monk and others use that design. But they were mostly long distance travelers who went by themselves and needed to store gear and keep it somewhat dry. It it would be similar to a kayak except of course it has a sail and it sits a lot higher out of the water than a kayak does. But you could see similarities in the design. If you look hard enough.

Dean Klinkenberg 24:26

There was a journalist with a couple of buddies who travelled in Rob Roy canoes down the Mississippi in 1879 or so, was when they did their trip. I forget how far south I got. I think they started around Itasca around Lake Itasca and made it at least to the Twin Cities and then maybe a little further south from there, and then wrote two or three articles about their experience. So if you’re not familiar with that, I’d be happy to send you that.

Mark Neuzil 24:54

Yeah, that’d be great. I love reading the old stories. And I love, I love them. Even more if they’re true.

Dean Klinkenberg 25:01

I’m pretty sure these were true. Unlike some of the other canoe trips, I read about. But so one thing I forgot to ask about is the paddles for the birch bark canoes. What were they typically made of, and were they composites of different materials, or were they a single cut from a single piece of wood?

Mark Neuzil 25:24

Yeah, normally cut from a single piece of wood. And again, it would be the availability of whatever trees were nearby. Could be ash. It could be something lighter than ash as well, like in the cedar family. And the paddle is, paddles were among the easiest things to make. So they could be expendable in those days, but they tended to be one piece, one piece of wood. And then again, the paddle shapes were different depending on what they were used for. So a voyageur’s paddle is looking, gonna look very different than the paddle used by somebody on a slow river or on a big flat lake where more propulsion might be needed but fewer strokes. A voyageur’s paddle is going to be long and skinny, because they, they used it so much, it needs to be super light and doesn’t have to have the big sort of beaver tail shape, flat shape, because it’s too heavy and too hard to pull through the water if you’re doing a million strokes a minute. So different paddles for different uses. And then of course, people that did, like racing, for example, may not have used a paddle at all but a pole and just pulled themselves along. In the shallower waters where they could do that.

Dean Klinkenberg 26:34

I had a chance to get a little taste of wild pricing with with a friend a few years back, and I discovered the poling is a lot harder than it looks. It takes a lot of practice to do that well.

Mark Neuzil 26:45

it does. And you got to have good balance. You know, when I was a kid, and maybe you had this too, Dean where, you know, my father in particular said don’t stand up in the canoe, you know? That was just one of the rules. Because if you did, especially when you’re 10 or 11, your balance may not be great. Mine wasn’t, you know–in you go. And maybe you’ve taken somebody else with you. So to keep your balance is the key part. But you know, you need the pole for balance, of course. But you need to be, you need to also have the, if there’s other people in the canoe, you need to have their cooperation and I’ve capsized more than once and anybody that’s been in a canoe, well, as much as I have, you’ve capsized plenty of times, but you know, it’s sometimes it’s your fault. Sometimes it’s not. That’s just all part of it.

Dean Klinkenberg 27:35

Exactly. Well, it’s okay, so we’ve covered the birch bark canoes. Let’s let’s move on to dugouts. We have more artifacts of dugout canoes, as you mentioned the finding… could you just tell a little bit about what they found at Newnans Lake in Florida, the breadth of that discovery.

Mark Neuzil 27:51

Yeah, it’s amazing, really. And so, Newnans Lake. Well, first of all, we probably should say that there was a drought, a bad drought a few years ago. It’s been a decade ago probably now, or a little less than that. A bad drought. And the water levels of the lake, of course, recede in a drought. And this particular drought was so severe that they receded to the point where people hadn’t, hadn’t seen it that low really in recorded history in terms of white settlement. And as the water level recedes and recedes and recedes, the, the evidence of old canoes buried in the bottom of the lake, of the lake start to show up. And archaeologists are called in and others are called in to take a look. And sure enough, there were pretty close to 100 dugout canoes that had settled in the muck of the lake. And they had been preserved by the mud and kept from deteriorating as one would expect from a piece of wood sitting in water. And I think there ended up being 96, if I’m not mistaken, boats recovered. We’re not all recovered. Some are left many, most of them were actually left in place. But a few were, were were pulled out to be examined for all the things that you’ve examined them for, and carbon dating and so forth. So they found out found to be thousands of years old. So if it wasn’t for the drought, those boats probably never would have been found. But it’s also offers evidence that the boats had been in North America for many, many, many, many thousands of years.

Dean Klinkenberg 29:31

Do you remember what kind of wood those particular dugouts were made from?

Mark Neuzil 29:35

You know, I don’t have it. I don’t know if that’s been determined off the top of my head. I know that in that particular region there are a couple of different trees that lend themselves, lend themselves to this type of wood, gommier tree would be one, cup oak tree would be another. I’m not sure if they were found in that region in Florida and it’s, it would be a little difficult to know if those boats were built there or, you know, built elsewhere and they got traveled, traveled there. But those would be the typical couple of the typical trees from the Caribbean at least. So from that, more or less from that ecosystem. In other parts, the other dugouts would be cedar for the most part, redwood type canoes, because that was those trees are big and those canoes could be strong and light and, and sort of waterproof because of the oil content.

Dean Klinkenberg 30:34

We have–I live in St. Louis, as I mentioned when we were talking before we started–and Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site is just across the river from me. They have a dugout canoe that was found in Arkansas a few years back that was dated to about 600 to 700 years old, I think. It’s, I’m gonna guess around 12 to 15 feet long, if I remember right. And from bald cypress, so pretty sure. It seems like every now and then one of these will turn up on a mud flat or sandbar somewhere as the rivers drop and this one was found along the St. Francis River in Arkansas. Along the Lower Mississippi, it seems like cypress and maybe cottonwoods are also pretty commonly used for dugouts.

Mark Neuzil 31:18

Cottonwood especially, yeah, because it’s available and it grows large, of course near the water. And you can get a, you can get a pretty good sized boat out of an old cottonwood tree, if you had to. I think the issue with cottonwood is the, the wood itself is so wet, so to speak, it absorbs so much water, it can be heavier. And then the problem you’ve got with it when it when you’ve got it dried out is it tends to warp. A little bit out of shape at time, so you won’t get the most beautiful looking canoe you’ve ever seen. But it’ll work. I mean, it’ll work just fine. It just might not be on the cover of a National Geographic anytime soon.

Dean Klinkenberg 31:59

Not going to be a centerfold anytime soon, right?

Mark Neuzil 32:01

No, no, but they do they do. And I’ve experimented a little bit with with cottonwood as well. But it’s just it’s kind of unsatisfactory. If you want a really smooth line, it just, it doesn’t. I suppose if a guy had a kiln and really worked at it, you could. But I’m pretty sure those didn’t exist in the old days. So.

Dean Klinkenberg 32:20

Right. Some of those, let’s back up. So the basic process of constructing a dugout was pretty time consuming and arduous as I recall. Can you just kind of describe the steps involved?

Mark Neuzil 32:33

Yeah, Norm and I considered it sort of like building a cathedral in Europe, you know, where you need the whole community to pitch in and help out. So typically speaking, what would happen and we’re talking about pre-Iron Age materials here, so fire was key to doing this. So once you found a tree that was of suitable size, chopping the tree down was probably going to be problematic with stone tools. And so typically speaking, what would happen would be the base of the tree would be burnt. And so you start a fire around the trunk, right at the ground level and burn away as much of that as possible, so you could push the tree over. And then once the tree gets pushed over, you could use, you could use your, your hatchets and axes to chop the branches off, okay? It would work okay. And then when you chop the branches off, that’s your fuel for your fire. So then you start another fire and you heat things like water or rocks in it. And basically you just start scraping away until you get a flat side of the trunk or flat side of the tree. And then you start to dig it out. And digging it out usually meant with a sharp side of a rock or clamshells, which had a bit more of a knife edge to them. But the way to dig it out was to start a fire and put coals on the top of the, on the top of the cut side. And then scrape the charcoal out as the coals burned into the hole. So hot water and coals, hot water and coals, scrape, scrape, scrape, you know? Several weeks later you, you’ve got something that looks a lot like a canoe. And it was a process that took many people, of course, and somebody had to turn the fire, and somebody had to have fuel for the fire and, and you needed, you know, the big clamshells and strong people to move it once once it’s finished. And Columbus brought an artist with him on his second trip here and the artists did some sketches of of those canoes being, they had never seen a canoe, of course, and so they did some sketches of natives building canoes. And they got most of it right, although one of the sketches, interestingly enough, has a square back, has the squareback canoe which I’m pretty sure It wasn’t needed for motors in those days. But the rest of its probably fairly accurate in terms of the, the tools that they had available to them. And then of course, once they got iron iron age tools, they’ve got knives and hatchets and so on that were were steel or iron, they, they could really go to town and a lot, a lot more quickly.

Dean Klinkenberg 35:25

Hey, Dean Klinkenberg here, interrupting myself. Just wanted to remind you that if you’d like to know more about the Mississippi River, check out my books. I write the Mississippi Valley Traveller guidebooks for people who want to get to know the river better. I also write the Frank Dodge mystery series that is set in places along the Mississippi. Read those books to find out how many different ways my protagonist Frank Dodge can get into trouble. My newest book, Mississippi River Mayhem, details, some of the disasters and tragedies that happened along Old Man River. Find any of them wherever books are sold.

Dean Klinkenberg 36:02

So once that basic process of excavating was finished, did they do anything else to the canoe before it was considered done at that point?

Mark Neuzil 36:12

Yeah, they oftentimes had to make the sides of the boat a little bit higher, depending on the size of the tree, of course. I’ve seen them done and seen evidence, you know, photographic and artistic evidence, of them done where the basic whole shape is crafted out of a single log, let’s say, but you want more freeboard, you might want well, depending on the use of the boat, you might want the sides of the boat to be somewhat higher. And so they would attempt to lash additional logs on the side to give you a little bit more, to give you a little bit more boat that way, depending on the size of the log that you start with. And again, most of these had some head seats, but most of them did not have seats. That’s pretty much it, and then off you go, you know? You tried to make it as narrow as possible. You tried to give yourself enough, enough rocker to turn it if you needed to turn it but most of the dugout boats were built for bigger waters, like the ocean or the Mississippi. So you didn’t, you really didn’t need to turn on a dime. Unless you were in the business of doing things like fishing, or, or something where you know, it’s like, oh, there’s my net over there, I got a turret you know, I’ve got to make a sharp turn and in the current to go to go retrieve those fish. But for the most part, those big dugout canoes were built to carry gear over long distances or people over over distances. And that’s what they were. That’s what they were good at.

Dean Klinkenberg 37:50

I remember reading that, I think there’s some question as to the authenticity of some of these stories, but when DeSoto led his army here to North America, after he died, and the remaining people were fleeing down river, they had these repeated assaults from indigenous people, Mississippian, descendents of Mississippian culture, the culture that started Cahokia, and one of the descriptions was a canoe, were canoes that were so big that there were 90 men in them, 30 on each side and then 30 in the middle. That would be an enormous dugout canoe I can only imagine the size of the tree.

Mark Neuzil 38:31

I I’m not sure about the authenticity of that account, but I I don’t doubt that there were trees large enough at the time for that to be possible. I’ve seen canoes 36 feet long, 38 feet long. It depends on how much room each person needed. It would probably not be an efficient fighting vessel with 90 people in it unless the plan was just to move them from point A to point B and and board another ship for example. Then yes, because you could outmaneuver a clumsy European boat pretty easily, especially with a bunch of paddlers. But if your idea was to storm another boat, then that would be, that’d be one way to do it. But my guess is that they needed more than one tree in some fashion. And it would be interesting to see that now in in the upper part of the river. And in the Canadian region, of course, Lake Superior now I’m thinking in the Great Lakes system, very common to have canoes 36, 38 feet long that were freight canoes basically, to carry the beaver pelts back to Montreal. And they they needed several people to paddle them as well.

Dean Klinkenberg 39:50

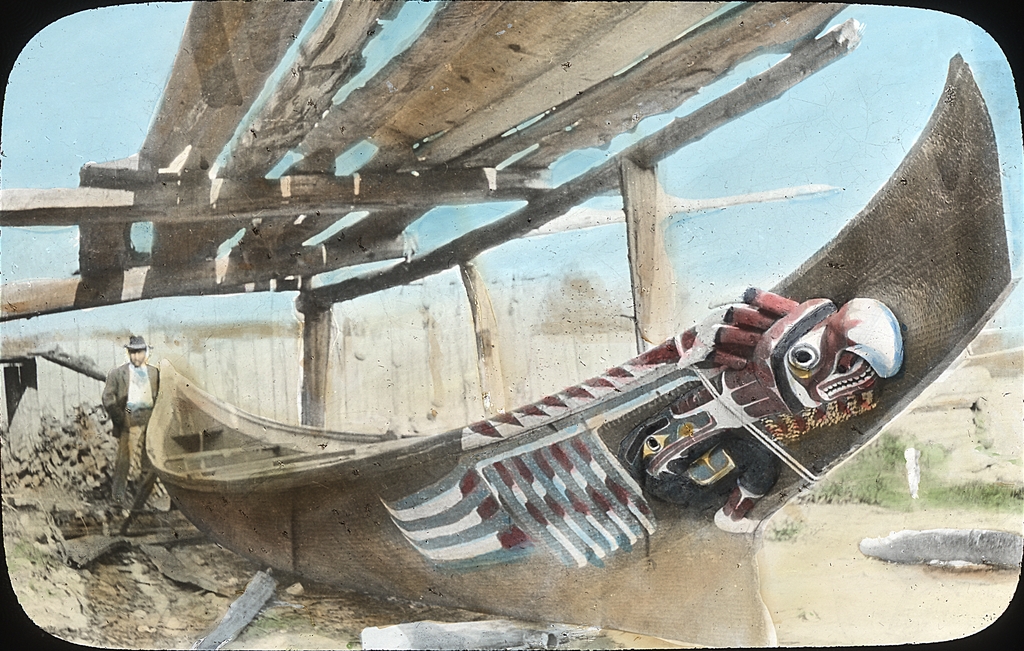

So right that dugouts, like birch bark canoes, there were variations in size depending upon what you needed it for. I think you had some interesting pictures that showed different styles of ornamentation, like they weren’t all just functional, sometimes they would add ornamentation to them to add their signature style to him.

Mark Neuzil 40:10

Some of the ornamentation was spiritual in a sense, some of them were ownership, like a brand on a steer, or something like that, some of the, some of it was was just artwork really, you know? You see images that look something like maybe, like cave paintings, for example, of animals or people. But you also see stars and the sun and fish and other things. And then, and then just sort of some symbols that probably stood for perhaps a tribe or clan, or maybe a time of year, depending on what the use was. One of the ways to tell whether you’ve got a real accurate birch bark canoe is by looking for those symbols. Those etchings of the best of the birch bark canoes, the bark would be collected in late winter. And when the canoe was made, the outside of the bark of the tree is the inside of the canoe. So the white part of the bark that you see really should be the inside of the canoe. So all those Christmas tree decorations of a little bitty six inch white canoes with latch, those are backwards, actually, those are inside out. They’re not accurate. The outside of the tree is the inside of the canoe. That shapes better that way but the, also the other reason that was late winter is there’s a growth on the inside of the bark of the birch tree that is kind of a dark brown that is only dark brown in late winter. And so just by looking at the hall, you can think okay, that bark was harvested in March versus that bark was harvested in September based on the color. The other thing that, that late, that late winter harvest does for you is you can etch in it better. It’s got a little bit of a kind of a fuzzy sort of covering to it and allows you to scrape those ornamental or spiritual symbols in it, in that late winter bark that you can’t do because that stuff goes away in the heat of the summer, in bark that’s harvested later in the year. So both color and sometimes the artwork on the boat you can, you can just determine when the tree was harvested by those kinds of clues.

Dean Klinkenberg 42:38

Fascinating. Well, I got one of those boy canoes you’re mentioned that are, that’s hanging from my rearview mirror. But so the bark is definitely facing the wrong direction.

Mark Neuzil 42:50

Yep, you gotta you gotta turn it inside out. Yeah.

Dean Klinkenberg 42:54

So let’s just kind of touch briefly on that canoes in the fur trade. And there were there were some variations in the canoes that were built for the fur trade as well. Was this sort of the first major adaptation of canoes for European immigrants to North America?

Mark Neuzil 43:13

I think the thing to remember about the fur trade is that the French were adapted the native customs and the British did not. So the French were far more successful and had a 300 year reign in North America, more or less, Canada in particular. Because they were smart enough to figure out that they couldn’t improve on the design of the canoe. And they didn’t try. Of course, they used indigenous paddlers and then eventually hired, hired folks, their own folks, but they basically kept the same system in place that the natives had been using for trade and transport. Because it’s hard to be, to canoe for, for all those things, especially portability, and speed. And one of the mistakes the British made when they got here was being British, they had to do it their own way. And of course, anything they did was better than anything that the natives did, or the French for that matter. So they started to abandon the canoe culture in terms of the trade and they were never as successful. They were never as as successful as traders. And of course, their empire here didn’t last as long either. In part because economically, they, they weren’t making a go of it, as well as they should have been. They attempted to bring British style boats over and British style boats just are not going to work for the most part. And in places like Canada where there’s multiple rivers and lakes and portages and you got to carry stuff and you got to carry the boats and you got to be able to steer them and you got to be able to face forward and all those things. So that’s that’s a real key. I think that is sometimes not as well understood as it should be.

Dean Klinkenberg 44:55

So for a while, this might have been in your book I’m trying to remember it seems like for for a certain period of time in the fur trade, most of the canoes that were, the French were using were actually built by indigenous boat builders.

Mark Neuzil 45:07

That’s correct. The Huron, there were other tribes of course, many Algonquin tribes, but there they were, they took advantage of native builders in their skills and instead of trying to do it themselves, they just sort of hired them out basically. And people like the Hudson’s Bay companies, like the Hudson’s Bay Company, just just hired native builders and said, you know, provide us with x number of canoes and, and off we go. And that’s, that’s what they did. It wasn’t really until toward the end of the third trading era, depending on when you dated that, that that process starts to end, long since, the French had long since left by then for the most part. And then you started to get some, some white builders, basically copying native designs, but moving us into an era and the big, a lot of the big birch trees were gone then you know. It was difficult to find materials pretty soon. You had to be crafting a canoe from three birch trees rather than one and all these things lend themselves to to the idea of just building a wooden boat rather than a birch bark boat or a dugout boat but a wooden boat maybe a lapstrake boat or, or something, something like that, that was nailed together. By 1850 you started to see the use of tacks and nails. And we can kind of date it from there.

Dean Klinkenberg 46:32

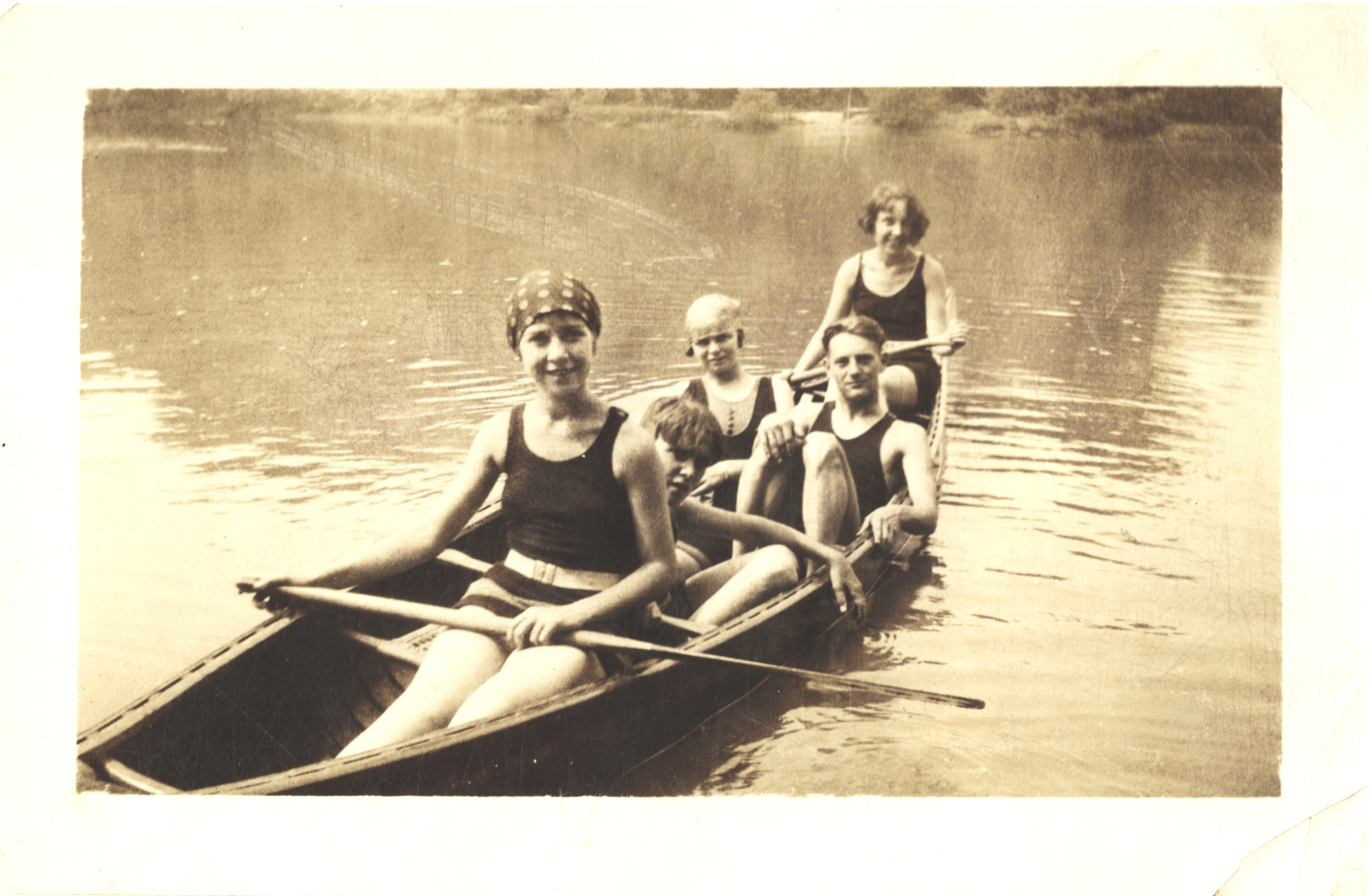

is that around the time when the canoes started to shift from purely functional to more recreational use?

Mark Neuzil 46:38

Right, and by about 1870 or so, you know, people still use them for work vehicles, of course, and transportation. But you also started to see sportsmen and women using them for fishing and camping and racing and so forth. And that ushers in an era of a new type of design of canoe, materials wise, because again, it was hard to find birch bark so you’ve got substitutes for birch bark. At first the canoes were built just from wooden slats, but they were leaky as hell, and not satisfactory to anybody. And so, by the 1890s, you started to see a canvas covering and the era of wooden canvas canoes starts in the late 1890s for real, and essentially the canvas replaces birch bark as the as the covering of choice.

Dean Klinkenberg 47:32

And I guess, though, it’s interesting, I don’t know that I’ve ever been in a canvas covered canoe. So is that still a technique that we’re using very often?

Mark Neuzil 47:43

There are a few builders around that will, will build you a wooden canvas canoe, and there’s an active small community, of course, that keeps that that alive. Many of the boats that you see that are wooden canvas now are older, wooden canvas. By the end of World War II, well, certainly by 1950, the wooden canvas, the major manufacturers had shifted over to aluminum or will, places like Old Town in Maine, of course and others. Thompson in Wisconsin made wooden canvas canoes, and it’s essentially a birch bark canoe with a canvas covering with a solution smeared onto the canvas to make it waterproof. Those boats are beautiful boats, they tended to be because you could shape the canvas and the boat any way you want. They tended to copy Native American designs and sizes as well. And they could, you could paint them, so they could look pretty. They tended to absorb water, an 85 pound boat at the beginning of the season might be 105 pound boat at the end of the season. So they did get a little heavy. But they were pretty sturdy. And all you had to do, really, after three or four years was tear off the canvas and put more canvas on. And you’re good to go again, and they’ll, those boats will last a very, very long time if you take care of them. But they are somewhat expensive to make. And of course, canoe builders are always looking for either lighter or cheaper. And so that pretty much doomed wooden canvas boats by about the late 1940s in the marketplace.

Dean Klinkenberg 49:25

I’m guessing the waterproofing coat did not include bear grease or any of those other traditional components.

Mark Neuzil 49:31

Sometimes it had a silver, very toxic silver component to it that proved to be problematic. But nowadays, that formula is a closely guarded secret. You can you can buy it occasionally from, but many of the builders don’t don’t let on as to what they actually use to cover their canvas with and it’s kind of an interesting subculture.

Dean Klinkenberg 49:57

Alright, so aluminum became kind of the material of choice beginning around World War II, then. I guess around the 1940s?

Mark Neuzil 50:04

Yeah, so what happened was the Grumman manufacturing company in New York, of course, were making Hellcats for the Navy. And once World War II ended in 1945, they didn’t have much of a market for their aluminum fighter planes anymore. So their chief engineer had gone on a long canoe trip in the Adirondacks with a wooden canvas canoe and came back and said, Man, this is heavy. And it was, and he thought he could, he could make it lighter out of aluminum. And there was some aluminum boat building in the earlier part of the century by the French and others, but it had never gone anywhere. But he took basically two, two airplane wings and flipped them around and bolted them together and thought he had something and the aluminum Grumman canoe was born. And it was inexpensive, and tough and durable, and somewhat lightweight, lightweight enough, and relatively cheap to manufacture, that it caught on. And by 1950 it, it leads the market in canoe sales. So for the first time that we were able to determine, if you look at overall sales, by year 1950 is the first year that aluminum canoes lead the market, and they do so for probably the next 25 years.

Dean Klinkenberg 51:24

Wow. When I went to Boy Scout camp, I hate to admit what year that was. But we’ll just say a while back, I’m pretty sure those aluminum canoes were already you know, 25 or 30 years old. At that point they were, they last a long time. They take a beating…

Mark Neuzil 51:41

They last a long time. That’s what they, that’s what they’re meant for. And they you know, it was $100, $130, maybe $160 at their peak. You don’t have to have a garage to store them. You can leave them outside all winter. It’s not going to hurt them any. You could throw them, you know, underneath your cabin. Nobody’s going to bother them. Mice are not going to chew through it. Nothing, you know. Squirrels don’t bother them. Nothing wrong with that at all. Now they’re of course, they’re super hot in a hot day in the summer. And they’re noisy as heck if you want to be sneak up on some fish, and you drop your Pepsi can in the bottom of the boat. They had some drawbacks. But all in all, they, you know, it’s hard to talk to a canoeist of our age especially who has not been in an aluminum canoe and had some memories of it.

Dean Klinkenberg 52:32

Tehy are kind of heavy compared to some of the contemporary materials, too. So what are we what are some of the more interesting materials being used today for construction of canoes?

Mark Neuzil 52:40

Well, by the 1960s, you could start to see the writing on the wall for the aluminum boats because of the introduction of fiberglass, of course, and there are plenty of fiberglass makers on the market. And then you’ve got Kevlar, which also was invented in 1964, as a matter of fact, Kevlar canoes. And then starting in an evenlater period, you got carbon fiber and its various forms. So you’ve got that, those are all on the high end. And then at the low end you’ve got the plastics, various kinds of ABS type plastics, as well. And so there’s a, there’s a wide range of materials on the market, now. You could, if you looked hard enough, you could buy everything from a new wooden canvas canoe to to a highly sophisticated carbon fiber canoe that might weigh less than half of what the wooden canvas boat makes. And there are still even three or four or five birch bark builders in the upper Midwest. Rarely can you get a boat made from one tree, but but you can still get them if you want them. And then occasionally, you’ll see some come up on the used market as well. But there’s a boat for just about every interest, if your interested, if you if you want to do so. And the, and the development of these new synthetic fibers gets more sophisticated every year. It’s amazing. I mean, you can buy a canoe now that is essentially the same materials as a Tour de France bicycle. And equally tough. Now it’s not going to be inexpensive, of course, right? But it would be it would be the latest and greatest in terms of weight and durability and that sort of thing.

Dean Klinkenberg 54:29

So it is interesting to me, like there is this timelessness as you said in the design of canoes and one of the lines that I really loved in your book was this idea that you know a person who was living a couple thousand years ago could show up today and look at a canoe and pretty much know what to do with it, right? they wouldn’t, they wouldn’t need anybody to orient them to how to use this thing.

Mark Neuzil 54:53

No, no. No instructed, no instruction needed. They could, they could probably whittle a paddle out of a nearby tree, hop in it and off they go. And so we say that’s one, that the pinnacle of design was reached many, many, many years ago. It’s just a question of materials. After that, and, you know, it’s that’s the fun part about it is, I think Sigurd Olson wrote once, you know, I’m paraphrasing here, but a person in a canoe has a connection to all canoes ever. Because it’s, you know, essentially what he’s saying, it is the same design, it’s the same boat. Yeah. And there is that nostalgia that goes along with it, and a little bit of history and so forth.

Dean Klinkenberg 55:37

So the romantic in me, though, wanders a little bit. We don’t build canoes anymore from the materials that are from the environment around us. And they’re, you know, most of the materials are manufactured from materials we get from anywhere around the world at this point. So have we, have we lost anything by paddling around in canoes that don’t have that connection to the natural world, to that direct connection to the natural world that they used to have?

Mark Neuzil 56:06

Well, yes, and no. It is still possible. I built a canoe out of white cedar, mostly white cedar, from wood gathered from near the Boundary Waters, for example. Now, I say that because it was a wood strip canoe. And of course, it’s covered with fiberglass after the wood hull is built. So it is a combination of old and new. So a person with about eighth grade shop skills could do that, if, if one wanted to. And I would recommend it. I actually learned probably more about hull design building my own boat than I would have from a book. That was one of the things that Norm, Norm had built four or five boats prior to our starting on the canoe book. And he said, If you really want to learn about hull design, you really should make your own boat first. And I’m like, hahaha, yeah, right. But I have some skills, and so, so I did that. And he was right. It gave me a more total understanding of the boat. And, and it was fun to, and it was fun. So but it’s a combination of old technology and new materials.

Dean Klinkenberg 57:15

And you had this opportunity, as I recall, because there had been a great storm that had come through with Quetico, or I forget where…

Mark Neuzil 57:23

it was, yeah. It was in both, both sides of the border, right along the border, as a matter of fact, and you know, tens of thousands of trees blown down. Now you can’t collect the trees from the parks themselves–that’s not allowed–but from cabin owners and farmers and so forth who bordered the area lost a lot of trees. And that’s where I got most of the materials. And the white, the white cedar tree is native to Minnesota. It’s also the lightest of the cedars. If you had a cubic yard of it, it’s maybe 25 pounds or something like that, maybe less. So you’ve got a really strong lightweight wood that that you can start with. And, and it’s local. And there’s plenty of white cedars around. It’s not like there’s a shortage of those. So, right, so we just kind of scrounged around and you know, found enough wood to build a 16 foot Canadian style canoe and off we went.

Dean Klinkenberg 58:25

So how many miles does that canoe have on it now?

Mark Neuzil 58:28

Well, I’d had probably, oh boy, that’s a very good question. I’m, it probably had 40 or 50 trips to the Boundary Waters over the years, plus the area lakes in the Twin Cities. And that one was sold, like my fleet rotates quite a bit. I’m never satisfied, I guess, but I think it’s now at a cabin in northern Minnesota being gently tended for and used on holidays by the purchaser.

Dean Klinkenberg 59:09

So I’m cognizant of the time and we probably need to wrap this up pretty soon. I’m just curious, like, do you have a story, one story about a particular canoe trip that really stands out, like something you really could not have done without being in, traveling by canoe?

Mark Neuzil 59:25

Well, I don’t have a particular, I mean, I’ve got lots of stories, but few that we have time for. But I would say, in general, because of the quiet nature of the boat, that it allows you to have interactions with wildlife that you would not otherwise have. Even in the hiking circumstance, you can sometimes sneak up on animals when you’re on foot, but in my experience, it’s not quite as easy. Whereas in a canoe, especially in a smaller bodies of water, and you’re so quiet, especially if you’re not talking or you’re not making other noises, that I’ve had the opportunity to be closer to wildlife than in any, you know, any other circumstance outside of the zoo. You know, many experiences with, with moose and calves and bears and, you know, waterfowl of all sorts, fish, of course. All those things happen because you can be quiet and part of the natural world without disturbing it very much. That would probably not happen if you were in a motorboat or or you know, another kind of circumstance, you’d scare them away, right? And those are the kinds of things I think about, rather than one particular story, is just moments where I might be… A couple of years ago I was paddling down a river with a friend and we were actually going downstream and a moose was standing on the shore about, I was gonna say about 75 yards away on the western shore, and it decided it wanted to be on the east side of the river instead of the west side right before we got to it. So it jumped in and swam right in front of us, you know, not 20 yards away, if even that and, and, and moose is a darn good swimmer, by the way. And the part that I remember the most is we just stopped and watched it and floated and it swam all the way across. And then it came out of the water at a portage. And it shook like a dog, which I had never actually seen up–and I’ve now since seen it but before I hadn’t seen it at that–it shook like a dog, which was amazing. And then it just walked down the portage like it was going to the next leg, which I’m sure it probably realized. So that was a marvelous experience that you would not have otherwise seen. Now the other thing I thought was what if I was portaging my canoe the other direction and the moose was coming. It was a fairly narrow trail. Yeah, that would be that would be another circumstance.

Dean Klinkenberg 1:02:15

That’s fantastic. And I think that I completely agree. I think that’s one of my favorite, one of the reasons I love being in a canoe so much is it does feel like you’re it’s easier to interact with the rest of the natural world because you’re quieter. It’s more like you’re a part of that world rather than, you know, just zipping through it. So well, thanks so much for sharing that. And for your time today. Is there a place where you keep an update on what what you’re working on next, a way for people to follow your work?

Mark Neuzil 1:02:44

You know, I’ve got a website, MarkNeuzil.com, that I try to keep up when school is not in session. And then on Facebook, there’s a canoes page where I post news stories as they come up on canoes and canoeing. And of course, every time a new boat comes bubbling up from the bottom of old boat comes bubbling up from the bottom of the lake, I try to post about it, and different things with manufacturers, and sometimes they’ve got a different kind of plastic that they’re attempting to use and new materials and so either of those two places are open to the public, I guess you could say. And then of course, you know, we love feedback. I love feedback from our book, all kinds of feedback. I give a lot of talks around the country, around the Midwest, mostly. I gotta tell you that almost every talk, somebody thinks that I’m the antiques roadshow guy about canoes, which I’m actually not. I don’t know, I don’t know if they have a canoe guy, but almost every time somebody will come up to me with an old photograph, and say, this is Grandpa’s canoe. And what they’re really asking me is: is it worth anything? What can I get for this? And I usually have to say, it’s worth a lot to you. Yeah, but that’s fun, too.

Dean Klinkenberg 1:04:10

So what’s the name of the Facebook group, then?

Mark Neuzil 1:04:13

You just search search for canoes in North America and it’ll, it’ll pop up.

Mark Neuzil 1:04:17

All right, thank you very much. I enjoyed it so much.

Dean Klinkenberg 1:04:17

Alright, I’ll post the link to that in the show notes too. So people can find it and to your website, as well. And to I guess the University of Minnesota Press is the publisher of the book. so I’ll put the link there to. Well, thank you so much for your time. I really appreciate this. This was a fantastic conversation. And like I said, I absolutely love this book, and I think everybody should go get a copy now. And so yeah, thanks for your time, Mark.

Dean Klinkenberg 1:04:55

And now it’s time for the Mississippi Minute. Mark’s story about his own memorable moments from canoe trips got me thinking about my own trips. I haven’t had quite as many trips as Marc has, but I do have a couple of memories that really stand out for me. In August 2014, I took a two day trip near the Mississippi Headwaters beginning about 16 miles down river from where the Mississippi begins at Lake Itasca. I began at Coffee Pot Landing, and I finished at Lake Irving at Bemidji. One interesting side note from this trip: the headwaters had apparently gotten nine miles closer to Bemidji than they had been a few years earlier when I compared my older Mississippi River Trail map to the new one. I don’t know who shaved off those miles–I’d put my money on Paul Bunyan–but I’m pretty sure it saved me some time. Later in the day of that first day’s paddle, I somehow managed to miss the area where I had planned on camping that night, so I had to paddle on into a marsh through anxiety and doubt and into the golden hour as the sun got lower and lower in the sky. I wondered if I’d have enough light remaining to get to the next campsite or if I should be figuring out how to sleep in the canoe. The river though, wouldn’t let me get too bent out of shape. The marsh glowed from the golden late day light. The breeze disappeared, and I began to feel as calm as the world around me. I saw more wildlife in those late evening hours than I saw the whole rest of the day: beavers, kingfishers, a trumpeter swan, lots of ducks, turtles, and more. I got to the campsite at Iron Bridge as the sun was setting with just enough light remaining to set up my tent and get my gear inside before the mosquitoes carried me away. I was beat. 11 hours of paddling to cover 25 miles will do that. Of course, it would have been 31 miles on the old map so lucky me. So it didn’t really matter when I discovered that the batteries were dead in both of my lights. I guess I hadn’t bothered to check those before I left. I just settled in and I went to sleep which came easily.

Dean Klinkenberg 1:07:09

Spending hour after hour alone in the canoe, I began to realize that solo paddling on a river offers some valuable life lessons. For example, a lake looks much bigger when you’re paddling on it into a headwind than when you’re standing on a boat ramp admiring its beauty. Here are a few more life lessons I picked up from that river trip. Around every bend in the river there is another bend in the river. You will get dirty and wet. Embrace it. Stillwater doesn’t always run deep. No matter how mad your skills and how well you prepare, sometimes the wind and the current will force you into a bank, anyway. The moment you stop paying attention is when you miss the trumpeter swan or you end up on a rock. It’s impossible to always pay attention. Whether you drift or paddle hard, you end up in the same place. So what are some of your favorite paddling stories? What life lessons have you learned in a canoe or kayak? I’d love to hear your stories. Share them with me at MississippiValleyTraveler.com/contact.

Dean Klinkenberg 1:08:21

Thanks for listening. If you enjoyed this episode, subscribe to the series on your favorite podcast app so you don’t miss out on future episodes. I offer the podcast for free but when you support the show with a few bucks through Patreon, you helped keep the program going. Just go to patreon.com/DeanKlinkenberg. If you want to know more about the Mississippi River, check out my books. I write the Mississippi Valley Traveler guide books for people who want to get to know the Mississippi better. I also write the Frank Dodge mystery series set in places along the river. Find them wherever books are sold. The Mississippi Valley Traveler podcast is written and produced by me Dean Klinkenberg. Original Music by Noah Fence. See you next time.