Drive anywhere along the Mississippi or most any other river and you’ll see a levee, an earthen wall that parallels the river to keep water in the main channel and out of the adjacent floodplain. In this episode, I talk with Nicholas Pinter about levees and the good and bad that has come with them. We discuss R the evolution in responsibility from local jurisdictions to the federal government, how levees have altered the ecology of big rivers, and who pays for them. We talk about how levees provide a false sense of security and the concept of residual risk, which is one way to quantify how much of our property and lives is at risk behind levees. We also talk about options for reversing some of the worst damage from levees and the obstacles to putting them in place.

Levees didn’t just rise on their own, of course. In the Mississippi Minute, I give a brief history of who built the levees and the deplorable working conditions that were often present in levee camps, especially for Black workers. And in the end, I offer a playlist of songs about levees and levee camps.

Show Notes

Support the Show

If you are enjoying the podcast, please consider showing your support by making a one-time contribution or by supporting as a regular contributor through Patreon. Every dollar you contribute makes it possible for me to continue sharing stories about America’s Greatest River.

Don’t want to deal with Patreon? No worries. You can show some love by buying me a coffee (which I drink a lot of!). Just click on the link below.

Transcript

Wed, Oct 18, 2023 2:58PM • 1:02:45

SUMMARY KEYWORDS

levee, flood, river, people, camps, floodplain, work, years, mississippi, projects, mississippi river, flooding, landowners, men, big, corps, residual risk, area, workers, easements

SPEAKERS

Dean Klinkenberg, Nicholas Pinter

Nicholas Pinter 00:00

But never giving into this temptation to say we’ve built the levee and solved flooding once and for all. Which we’ve heard historically, again and again and again, over, as you said, time periods of decades to centuries, parallel over most of those decades with a history of levees failing again and again and again, after people heard it would never happen.

Dean Klinkenberg 00:43

Welcome to the Mississippi Valley Traveler Podcast. I’m Dean Klinkenberg and I’ve been exploring the deep history and rich culture of the people and places along America’s greatest river, the Mississippi, since 2007. Join me as I go deep into the characters and places along the river and occasionally wander into other stories from the Midwest and other rivers. Read the episode show notes and get more information on the Mississippi at MississippiValleyTraveler.com. Let’s get going.

Dean Klinkenberg 01:15

Welcome to Episode 30 of the Mississippi Valley Traveler Podcast. The discussion in this episode is another topic inspired by the 30th anniversary of the flood of 1993. I talk with Nicholas Pinter, who has spent much of his career studying levees and studying issues like how much risk still exists to people on the supposedly dry side of levees. We have a pretty wide ranging discussion, talking a little bit about the history of levee construction along the Mississippi and the evolution in responsibility for who should pay for it and maintain those levees. We talk about how levees have changed the Mississippi River and its tributaries. And some options being discussed for reversing the damage and the unintended consequences of levees, as well as the barriers that are in place that make some of these changes very difficult to implement. We talk a little bit about who really benefits from levees and get into some of the thorny politics about who really should be expected to allow their land or property to flood. There are a lot of difficult and complex issues. I’m still sorting through myself related to levees and levee management. And we plug away at that a little bit and do our best to try to make sense of things for ourselves. I hope you’ll find the discussion interesting and useful. And I’d love to hear what you think. You can drop me a line at MississippiValleyTraveler.com/contact or send me an email at dean@travelpassages.com or just leave a comment for the episode on the MississippiValleyTraveler.com/podcast and just click on the link to this particular episode. I will post a few things in the show notes that might interest you including the website that Nicholas Pinter mentioned for UC Davis for their water blog, and also a surprise that I mentioned in the Mississippi Minute. As usual, thanks to all of you who have shown me some love through Patreon. If you want to join that community, go to patreon.com/DeanKlinkenberg. And you’ll find out more there. Also, thanks to those of you who have shown me some love by buying me a coffee. If you’re interested in knowing how to do that, just go to MississippiValleyTraveler.com/podcast and you’ll find a link to buy me a coffee and feed my caffeine habit. Both of these methods, Patreon and buying me a coffee, help support the podcast and allow me to keep it going. So thank you very much. And now on to the interview.

Dean Klinkenberg 04:11

Nicholas Pinter is the Roy J. Shlemon, Professor of Applied Sciences and Associate Director of the Center for Watershed Sciences at the University of California Davis. He’s an expert on earth’s surface processes including flooding, river systems, hydrology and natural hazards assessment. He’s the author of several geoscience books and has been the recipient of a number of awards including the John D. And Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Charles A. Lindbergh Foundation and recently from the European Commission, the Marie Curie Fellowship. He’s done a lot of his work along the Mississippi River. He’s the leader of two National Science Foundation funded projects analyzing flooding and flow dynamics of the Mississippi River and its major tributaries, and has studied and written about the effects of levees and levee construction upon river dynamics, flood frequencies and understanding and managing risks from flooding. Welcome to the podcast, Nicholas.

Nicholas Pinter 05:02

Thank you. It’s a pleasure.

Dean Klinkenberg 05:04

Well, I thought maybe we would get started just with kind of a quick review of the history of levee building along the Mississippi. It’s not anything new. Like it’s a very long history. Can you kind of give us a quick synopsis of like when levee construction began and and it’s evolution over, oh, just 200 years and do it in 20 words or less? Just kidding…

Nicholas Pinter 05:25

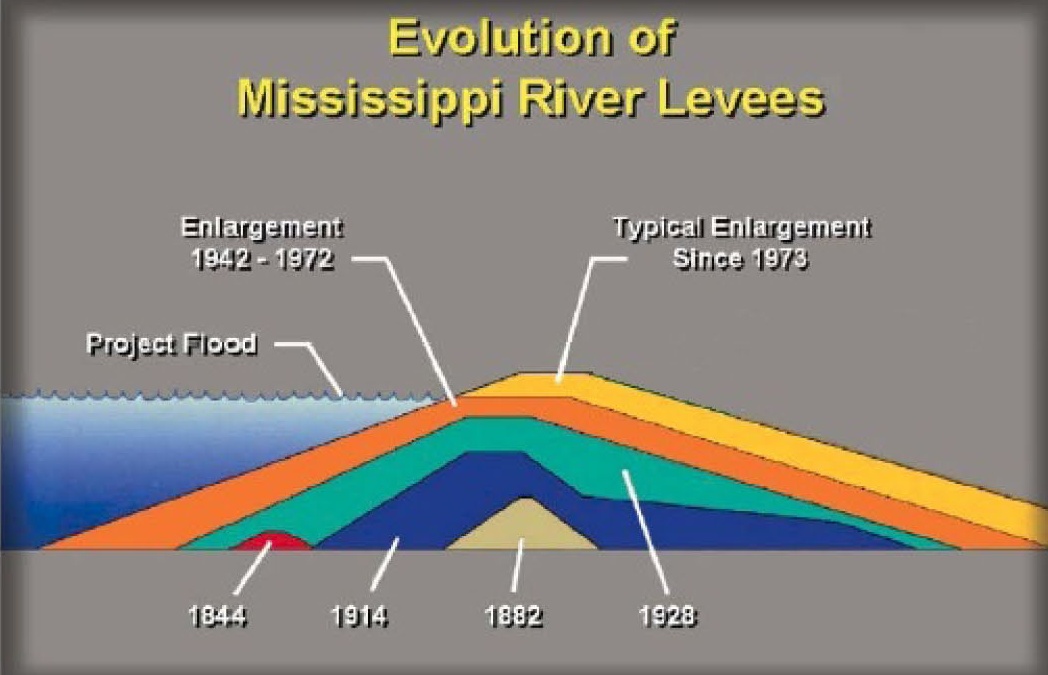

At least 200 years. Yeah. So levee construction along the Mississippi began mostly in New Orleans. And basically, wherever people moved to, at a certain concentration, they built levees to keep water in one place and out of others. Generally those levees have increased in size and extent, over that many centuries history of developed western development of the Mississippi River Corridor.

Dean Klinkenberg 05:59

I guess my math was off, because really, we’re talking 300 years of history or something like 1712 or so was when the first levee went up around New Orleans, and just two or three feet tall at that point. Of course, you know, what people often forget is that where the French Quarter is in New Orleans, that was high ground in that area. That was a natural levee. Rivers kind of, I won’t, we won’t go into the details of that. But you know, rivers that flood a lot, kind of create a high bank close to the main channel that’s a natural levee. And throughout history, people tended to kind of live on those areas of high ground when there wasn’t much else around.

Nicholas Pinter 06:37

So there’s this universal thing we’ve seen in history and archaeology that people like to keep their feet dry. That pretty much governs the development, occupation of floodplain areas.

Dean Klinkenberg 06:50

Right. Now, the other part about this, though, is that and I think we’ll get into this a little bit later, but the these levees haven’t, let’s say they’ve required constant adjustment over time. And I forget the exact numbers now. But there’s a levee down in Louisiana that had to be raised something like 20 to 30 feet above its initial height by the end of the 19th century because river levels kept coming up and up. So that’s been another common theme is that after a lot of floods, levees tend to get built higher.

Nicholas Pinter 07:21

I think all of those lower Mississippi River started as you know, nothing to very small. And there are now towering three story structures in the lower Mississippi River. And usually when they’ve been raised is right after they broke or overtopped the last time.

Dean Klinkenberg 07:39

Right. And we’re not done with that it seems. I pulled up a quote that I found like In 1993, Hannibal got a brand new flood wall that was supposed to be five feet above the highest crest that they could expect the river to reach. And instead, you know 1993, the water came within 27 inches of the top. And there was a former mayor of Hannibal that was quoted as saying that their floodwall set the record for the shortest time between the completion of an Army Corps project and its obsolescence.

Nicholas Pinter 08:11

That’s a good one. And yeah, there’s a lot going on in Hannibal and throughout this system.

Dean Klinkenberg 08:16

So one of the conflicts, I think, over time is from my understanding some of the earliest lawsuits in American history were related to levees. There’s always sort of this dynamic, or there used to be this dynamic where you neighbors across the river might build a little higher than the people across the river from them. And that could create a higher flood risk for people on the other side of the river. We’re still kind of having that debate, though it seems, right? Especially in that area around Hannibal.

Nicholas Pinter 08:49

So that’s the debate around Hannibal, for the last few years, and this, this goes way back. You know, the classic example is the 1927, the great lower Mississippi River flood. And basically the city of New Orleans was saved by breaching the Plaquemines Parish levee and allowing the water into there so that it wouldn’t go over the top and into New Orleans.

Dean Klinkenberg 09:14

So they sacrifice people in the more rural area down river to protect the city.

Nicholas Pinter 09:19

Correct. That’s exactly what they did.

Dean Klinkenberg 09:22

Yeah. So in the early years, you know, levees were basically a local responsibility. And I think the colonial governments in Louisiana had laws that required landowners to build levees to a certain height and maintain them. But today, we sort of have this mishmash, like a lot of the levees, especially in the lower part of the river now are federally managed. How did we get from these private, privately owned private responsibility for levees to becoming a federal responsibility?

Nicholas Pinter 09:56

Right, Dean, you’re correct. That’s the history of sort of the evolution of levee responsibility, but it also parallels sort of growing federalism across the US. So that parallels the responsibility for flood recovery. So in the early years, there was no FEMA. There was no personal assistance, individual or assistance after a flood, individual communities were on their own, with only like the Red Cross private private organizations stepping in. So we’ve evolved from that to more federal system of bringing in centralized resources. And it is largely the same trend in levees that they were initially locally constructed, locally operated, locally maintained. And we’ve evolved to the point where many, certainly not all levees, are often federally constructed and federal responsibilities.

Dean Klinkenberg 11:02

So on the lower part of the river, the MRT, that was the Mississippi River and Tributaries Project. As if I remember this, right, initially, there was a cost share when that was first passed. But I think after the 1927 flood, Congress basically waived that. So the state we’re in today is that pretty much all of the flood control systems south of Cairo, Illinois, are federally funded and managed.

Nicholas Pinter 11:32

So right, and that cost share issue again. This is a political issue and it continues to the present day. There’s good reasons to have local skin in the game, as they say, before anything is built, otherwise bad things get built. But in the spotlight of public attention after a big flood, those are often waived.

Dean Klinkenberg 11:53

Right. I remember I was at a…it creates some unusual dynamics too though. I think I went to one of the, I think it wasThe High Water meeting for the I just lost the name, but for the for the Corps when they were wanting to do two trips a year where they solicit input from folks. So I went to this one in Hickman, Kentucky. And it was a, I was kind of surprised at the tone of it. A lot of it was local folks coming to the Corps and asking for money for projects. There was I know, there was a Levee District in Southeast Missouri that needed to replace a pump. And they basically were going to the Corps and saying, please pay for this new pump for us that we can’t afford ourselves. I’m not like a knee jerk, small government person by any stretch of the imagination. But it seems a little unusual that we have this system we’ve built that is beyond the capacity for local communities to support from their own resources.

Nicholas Pinter 12:57

Yeah, we absolutely have. I mean, the demand for these kind of projects, investments is massive. So the locals go with this huge long shopping list to the Corps. And then the Corps approves some smaller subset of that. But then Congress only appropriates money for an even smaller subset of those projects. So there’s this decades long backlog of unbuilt projects, some may be needed, some maybe not.

Dean Klinkenberg 13:29

Right. So let’s kind of get into the system that we have today. So we’ve engineered the river, the Mississippi in ways that I think would shock Mark Twain, for sure. How have the levees that we’ve built, altered the the natural Mississippi?

Nicholas Pinter 13:54

I think a lot of people would be shocked if they could see the full magnitude of change of the Mississippi and its major tributaries. So large portions of this river are essentially man-made constructs today. So, Mississippi, the Missouri is particularly striking. The channel is in many places a third of its original width. A third of the width that Lewis and Clark navigated. It’s been constricted for the benefit of navigation. Also, it’s created a lot of new arable occupiable floodplain land. And then when you’re occupying and farming the floodplain, there’s this pressure to keep the water out during flood events. And so levees are our principal tool in the US and perhaps worldwide to do that.

Dean Klinkenberg 14:47

So we’re not unique in our use of levees, I assume. I know Europe’s got plenty of levees too and other other other places around the world are using levees as well. Apart from the cost in terms of dollars and cents of all this work that we’ve taken on, most of it probably really is in the past 100 years. What has what does it cost us for in terms of the river in terms of the rivers ecology or the rivers behavior?

Nicholas Pinter 15:16

Yeah, so there’s lots of consequences of confining flow to the channel, keeping it off the floodplain, that engineers and others had no idea about 100 years ago. And now we can talk about some of those ecological, hydrological consequences. They’re significant enough that there is increasing pressure to move the other way to set levees back to to increase the connectivity, hydrologic connectivity with a floodplain. And that is for distinct reasons, both practical and ecological. So the ecological benefits are that you’ve essentially lost massive wetland. So a floodplain is a natural wetland habitat, with benefits for fish and fowl primarily, but lots of other things. But then, the other reason that people are looking at levee set back is purely practical. And that is that a tightly constricted river channel means that when a flood comes through, it comes through higher than it would otherwise be. So there are local residents. You talked about other places in the world, the Europeans are leading on this where their principal tool for flood protection these days, is setting levees further back from the river than they were originally.

Dean Klinkenberg 16:43

Well, to me, like that seems like a massive long term project for us along the Mississippi given the scale of what we have in place right now. So how are they doing that in Europe?

Nicholas Pinter 16:58

It’s massive and expensive. And it’s not universal. So they very selectively pick spots where there’s room for the river, where you can create a new bypass channel or a setback levee or something like that. And where the benefits are the greatest, both, again, both ecological and flood control benefits are the greatest. So it’s very selective in part because it’s so expensive. And there’s opportunities for projects like that in the US. So I’m headed tomorrow to the Pajaro River here in California where they’re just initiating a levee setback project there after catastrophic levee failure this last winter. Most of the levee setback floodplain reconnection projects in the US and worldwide are small in scale. But we’ve studied, so you can create a lot of flood reduction benefits for urban areas, if you are willing to put some water on some agricultural land in the surrounding areas.

Dean Klinkenberg 18:07

Right. So that kind of touches on part of the political problem with this, though, right. There are a lot of agricultural interests that don’t want any water coming on their land and think they’re being sacrificed for the benefit of cities.

Nicholas Pinter 18:25

Well, that is an almost universal challenge to these projects. And there are success stories. So in my backyard here, part of the the more than 100 year old flood protection system for the city of Sacramento is a flood inundation easement through what is known as the Yolo Bypass, they can send up to 80% of the water of the Sacramento River through this agricultural area. And it’s a done deal here, which is makes it easier. But there was resistance at the time. And there’s happy coexistence 100 years later, that, that the water is on there during the wet season, which happens to be the winter here. And they get here, they get two and three crops per year out of that area during the summer when it’s not an issue. So you can work these things out. But just the fact that there are solutions doesn’t untangle these political knots, right? These are long-standing tensions. Rural versus urban, wealthy versus poor and with some odd reversals of that relationship. These are very thorny problems.

Dean Klinkenberg 19:40

Right. And, you know, I’m, I know, like, one of the things that jumped out at me when I was researching some of this a few years back, you know, that it’s kind of hard to to ignore that as soon as the levee is built, the value of the land on the dry side of the levee is, you know, just skyrockets. So, I think in the Sny District in Illinois, I think I saw some estimates that the land became something like 10 times as valuable after the levees went up. So people have a lot of financial investment in keeping that system as it is for situations like that. And are there mechanisms to offer compensation during periods when they’re flooded? What’s part of the discussion for that?

Nicholas Pinter 20:22

Yeah, there’s lots of ways to do it. When you can get over that initial hump, which is, call it political. It’s really psychological, sociological resistance to this kind of solution. Yeah, I mean, you can purchase land outright, you can purchase inundation easements, because, again, 95% of the value of the land is still there, when you let it flood occasionally. There’s wetland reconstruction credits that can be sold. So we’ve been working with venture capital, actually, they invest in these kinds of things. Wetlands restoration projects. There’s lots of tools that could be used creatively if people were open to these options.

Dean Klinkenberg 21:11

So that’s the trick is like, how do you open their minds to these possibilities? Do you have any success stories about that any stories you’ve come across where people were able to turn, you know, change their minds about this?

Nicholas Pinter 21:24

Yeah, so there’s a growing number of floodplain reconnection projects. I can think of some along the Mississippi River corridor. The most recent successes have been on the West Coast. People trying these things. So again, in the backyard here, the Cosumnes River, the Nature Conservancy, and a broad alliance stepped in to create a setback project there that helped significantly avoid flood damages this past very, very wet winter in California. There’s a new project, I can’t remember the name of it in Washington State. These things are going in, they’re generally small scale. Because those make them more tractable. Those make them more affordable. But there are definitely case study success stories to look at.

Dean Klinkenberg 22:24

And it seems like, at least probably, in some cases, the best opportunity to do something different is maybe after a big flood or after some levee failures when you’re gonna have to rebuild some anyway.

Nicholas Pinter 22:34

So absolutely, logically, that is we can talk about it, that is the window of opportunity to do it. Except when you make this so incredibly complex and difficult. So I told you, we’re working in the Pajaro River, which the levee breached this winter, flooded the poor, rural, mostly Hispanic community of Pajaro. It is being rebuilt in place, even though there are blueprints on the shelf to set the levee back. And that’s because it is politically mandatory, essentially, to get the protection back. And it takes so much – it’s land acquisition, it’s the legal research, that somehow it’s worth rebuilding that levee in place only to maybe tear it down a couple of years from now, to rebuild it in the setback location. I’m always amazed when I hear that. But the momentum the inertia is so great to get one of these projects going. That’s where we’re at this year.

Nicholas Pinter 22:34

Wow. That’s a little discouraging. As, like you said, that’s a golden opportunity to do something that’s already been talked about, and they’re already plans in place, but there’s still those political or psychological barriers to following through with it. Yeah, I’m gonna have to think about that one a little bit more. Who do levees ultimately benefit?

Nicholas Pinter 24:06

Yeah, I mean, it benefits the people behind or inside the levee. To the detriment in some cases of the organisms who live also within the levee, but also the people who live on the other side of the river, upstream and even downstream.

Dean Klinkenberg 24:24

Right, and I obviously like everybody who lives behind the levee in a floodplain benefits from not getting flooded. But the economic benefits aren’t really equally distributed either. I go down to Mississippi fairly often. And we’ve had big levees down there for 100 years. And it doesn’t seem to erase the poverty in the Mississippi Delta. It’s still probably the poorest part of the country. But it certainly has helped some agricultural interests grow crop crops more consistently and make money from that. So it seems to me sometimes the benefits from the levees are still pretty unequally felt.

Nicholas Pinter 25:05

So, right. So just remember that our concepts of equity, that’s really a modern day paradigm, that is not the basis by which these levees were built. And I would argue that they have not served equity well at any point. During that history. There have been some interesting inversions. I know I’m not a sociologist, but just go back to the narrative that 1927 flood that was wealthy New Orleans, flooding poor rural areas, behind levees around it. So that’s not really the reality today. So a large swath of US agriculture, I’m willing to say not all but a large swath, is very, very wealthy, industrialized, centralized, often corporate owned. And it’s often levied agricultural areas versus now poor, urban areas, urban populations. There’s been inversion of that sort of equity divide.

Dean Klinkenberg 26:09

Right, like, was it 2011, when they blew the levee, the Bird’s Point Levee in Missouri and flooded farmland in Southeast Missouri, in order to spare some flooding in Cairo, Illinois, which was a largely African American and quite poor community.

Nicholas Pinter 26:25

Yeah, with again, funny optics and politics. So right, so most most of the landowners in the Bird’s Point floodway were very wealthy, and very white. And with Cairo, the opposite, with the exception. So within the Bird’s Point Levee was the community of Pinhook, which is a historical community founded in the floodway, because they weren’t allowed to live anywhere else, basically, to establish themselves anywhere else. And they were held up as the victims of the activation of the floodway. When in fact, if you add up the total number of dollars of damage and everything else, it was really the opposite. It was mostly large, centralized landowners who were impacted by that.

Dean Klinkenberg 27:10

Right. And I don’t remember how this worked, but there were easements that were very old, to flood that area. Did the landowners get any compensation in 2011, for having their their farm fields flooded?

Nicholas Pinter 27:25

So what I do know, Dean is that the landowners or their ancestors or progenitors on the deed to that land were compensated, those easements were purchased in the 1920s and ’30s, prior to construction of the floodway. I am sure, I don’t know. But I’m almost sure that there were additional crop payments and other easements because that’s the way the the agricultural industrial complex is built in the US. I’m sure there were additional payments in 2011. But again, that if you bought a farm in the Bird’s Point Levee, it’s written into your deed that should the flood level at Cairo go above a certain point. And that’s changed over time, your land will potentially be flooded. The problem was that it had never happened, right. So people forget had forgotten that little line in their deeds. So our comparable floodway here, this Yolo Bypass that I talked about, one of the benefits is that it’s flooded much more regularly. So people are not given the chance to forget conveniently forget and then object as strongly as the people did in Bird’s Point taking it all the way to the Supreme Court in 2011.

Dean Klinkenberg 28:42

Right. I think was it 1937, I think, was the only other time I think they activated that, which was a long time ago. There probably weren’t a lot of people around who had in living memory.

Nicholas Pinter 28:56

You could be right. It could have been activated in the ’37 flood.

Dean Klinkenberg 28:59

Yeah. And it was fairly recent at that time, if I remember, right, they hadn’t completely finished securing all the easements yet either. But anyway, that’s a whole nother story. Maybe we’ll do a show sometime just on the 1937 floods. Since that one is not as well known and had some very big drama to it as well.

Nicholas Pinter 29:17

It certainly did. Yeah, that was a big Ohio and Mississippi River flood.

Dean Klinkenberg 29:23

Hey, Dean Klinkenberg here interrupting myself. Just wanted to remind you that if you’d like to know more about the Mississippi River, check out my books. I write the Mississippi Valley Traveler guide books for people who want to get to know the river better. I also write the Frank Dodge mystery series set in places along the Mississippi. Read those books to find out how many different ways my protagonist Frank Dodge can get into trouble. My newest book “Mississippi River Mayhem” details some of the disasters and tragedies that happened along Old Man River. Find any of them wherever books are sold.

Dean Klinkenberg 29:58

So do levees provide a false sense of security?

Nicholas Pinter 30:03

Absolutely. Right. So I think you’ve talked with General Galloway, former commander of the Corps of Engineers, and he’s widely quoted as follows. Let no one believed that because you’re behind a levee, you are saved. And that’s the nice version. All their academic colleagues have rephrased that as follows. There are two kinds of levees, those that have failed, and those that will.

Dean Klinkenberg 30:32

Right. So, there can be long time periods, though, between when leeves fail, it’s been a while since they’re, you know, they had water in Coahoma County, Mississippi, for example. So how do we manage expectations? I know you’ve done a lot of work trying to quantify what you call residual risk. Why don’t we start there? Why don’t we tell first, tell me a little bit about how you define residual risk. And why don’t we start with that.

Nicholas Pinter 31:06

Yeah, so residual risk is just what General Galloway said that you can have the biggest, seemingly the safest levee in the world. But there’s also, there’s always that slight possibility, small percentage chance, the levee will either be overwhelmed by a huge flood larger than it was designed for, or have some unrecognized flaw and will fail otherwise. So any farm, any house, any city behind one of those structures always has this small percent chance of things going bad. And that has to always be recognized. So when you’re looking at the long term flood risk flood exposure along any river, you know, that it’s whatever the hydrology is, it’s going to be 100 year flood or 1% annual flood outside the levees, but there’s also this always this slight percentage chance, even behind the levees, and you have to factor that in and make appropriate planning and decisions.

Dean Klinkenberg 32:06

So how, how would you recommend policymakers use those numbers? And like, what what would that look like? If you put together a report on residual risk, but it’d be probabilities of damage? Would it be an estimate of how much the dollar value of potential damage? What would that look like?

Nicholas Pinter 32:25

Yeah, so estimating, “quantifying levee fragility”, the engineers call it. Which is the possibility of a levee failing before it’s overtop, it’s really tough. It’s an intense geotechnical homework exercise. And I would say any estimate is rough at best. So what’s the what’s the possibility of a levee failing, we know it’s more than zero. And it’s less than it was. And so it’s some number in between. And what we agree on is that if you’ve got a big city or something behind a levee, you want to reduce that number. So, so we agree on certain things. You’re never gonna get a 100% reliable number. And we agree that there are certain tools for coping with that residual risk as part of a broader package of flood risk. And it includes insurance. It includes making good decisions beforehand. Maybe the most important thing, but never giving into this temptation to say we built the levee and it solved flooding once and for all, which we’ve heard historically, again, and again and again, over, as you said, time periods of decades to centuries, parallel over most of those decades with a history of levees failing again, and again and again, after people heard it would never happen.

Dean Klinkenberg 33:48

Right. Right. No, I like you’re going back to your quote, you know, those two kinds of levees so well, so on the dry side of the levee on the I don’t know, what will say, the dry side of the levee. There is, you know, there’s not everybody’s at the same risk of flooding, there are some elevation changes oftentimes in the floodplain and some people are in slightly higher ground and may be at less risk than others. But apart from that, the way our system works right now, is that what – is it you don’t really have to buy flood insurance if you’re on the dry side of the levee, unless you’re in an area that has what a 1% chance of flooding in a given year or something like that?

Nicholas Pinter 34:31

Yeah, so I mean, the the purpose of levees generally is to keep people dry on the dry side, but practically, oftentimes, the goal is to achieve FEMA accreditation of your levee so that people in that dry side area don’t have to buy their flood insurance. Which is a shame because again, it’s a viable tool for managing your residual risk and the levee once accredited, takes that requirement away, but maybe more importantly, significantly reduces the premium for people who do choose, you can always you’re always allowed to buy the flood insurance behind there. And it’s often a wise decision depending on your levee, depending on on climate change, but insurance penetration insurance rates are low, even on the wet side of the levee. To say nothing about the the dry side.

Dean Klinkenberg 35:33

Right. And we’re at a point now where major insurers are pulling out of disaster prone areas as it is Florida. I know they’re having big problems down there finding private insurance companies. As much as it’s easy to pick on the insurance companies, in their slight defense, they’re just responding to the bottom line, right? That there have been too many expensive disasters, and they can’t stay in business if they continue to insure properties like they have.

Nicholas Pinter 36:02

Right. So. So magnification of flooding, from climate change, and other anthropogenic drivers is not the insurance company’s fault. They’re trying to play the numbers game to stay profitable in that in that environment.

Dean Klinkenberg 36:17

And I don’t think there are many private insurers that offer flood insurance. Even the people who live on the dry side of the levee that’s a federally subsidized program. For the most part, private insurance companies won’t enter that market, because I assume they think it’s too risky to them.

Nicholas Pinter 36:33

Well, they’ve been reentering it. But what’s interesting, different kinds of insurance, right, so we’ve been in California seeing big swings in the wildfire insurance market. But what led to the creation of the US National Flood Insurance Program in the first place, the series of disasters, originally the 1960s, when insurers had pulled out of that market, after taking a bath, if you will, of losses, so we’re sort of reentering that environment, that the insurers are sort of nudging their way back into the flood market, but they’re running screaming away from other areas, climate driven risk.

Dean Klinkenberg 37:12

Interesting. So how do we balance like, we want to be humane with people, right? We don’t want people who’ve been through a disaster to be left hanging and desperate. But at the same time, it seems like the system we’ve created with, I know the Flood Insurance Program has had some modifications in the last decade or so. But it basically just enabled people to stay in risky places and rebuild over and over. And some of that is still seems like it’s still in place. So how do we find the right balance between, let’s say, providing some financial incentive for people to assume more of the financial risk of living in areas that are disaster prone, while not being too punitive about it?

Nicholas Pinter 37:57

Yeah. So Dean, what I always say is that NFIP is it has its issues. It’s at best a qualified success. But it’s it’s been a whole lot better than nothing at all. That if you reverse back to mid 1960s, just getting whacked with one national flood event after another. So we’re better off in uncontrolled floodplain development at the time, right? So we’re better off than we were. Which is not to say that it’s a perfect system. It’s gotten better, but it’s by no means there. So to me, the long term strategy, strategic precept ought to be the number one goal is avoidance. So FEMA has been successful, where it it has deterred development of the floodplain. And it has done that successfully. Where it has failed is as a tool for allowing in some cases, even encouraging continued floodplain development. So you’ve maybe seen, so what we what we’ve sort of promulgated is the levee sniff test. So levees sort of enabled and powered by NFIP regulations and financing. They’re like the dubious Tupperware. New levee project is like the Tupperware with some strange food in the back of the fridge. That before you open that up and bite into it, you want to be doing three things. You want to be sniffing it. Is this is this viable? So the first sniff is, is the levee project going to protect pre-existing infrastructure already there? Is that infrastructure concentrated and that’s not farmland that could probably continue doing its thing, even with the occasional inundation and so the pre-existing thing, oh, and high in value. So the pre-existing thing is the most crucial. So this avoids what we think is the worst case combination of NFIP regulations and and levy enablement. And that is Field of Dreams, where you take a great big, basically unoccupied area, build a levee behind it, and then fill that with 1000s in some cases, hundreds of 1000s of people, and millions, often billions of dollars of infrastructure. That when you multiply those billions of dollars of infrastructure by even a miniscule residual risk, as we discussed earlier, you end up with massively more risk after the levee was constructed than before it existed.

Dean Klinkenberg 40:49

Right. And the the flip side of that, it seems to me sometimes is it also leads to a bit of circular logic when the levees hold that you’ll see the Corps will put out a statement – the levees prevented x amount of this many billions of dollars of damage. But that damage wouldn’t have happened. It wouldn’t have been a possibility if they hadn’t developed the floodplain in first place. But I live in an area that you know, we’re very familiar with this dynamic. As you know, I’m in St. Louis and after the 1993 flood out in Chesterfield Valley, you know that the Missouri River levee flooded, broke out there in 1993 and flooded that area. And then within a couple of years, they managed to persuade Congress to pay for a brand new levee for them that was even taller than the previous levee, and the area just has exploded with development now. And it’s a fairly compact floodplain. If that area, or I guess I shouldn’t say when that area floods again, you know, the damages the you know, the dollar value of the damage is going to be far more substantial than they would have been even in ’93.

Nicholas Pinter 41:55

Right. And so again, this is a case like downtown St. Louis, you got to flood wall. I would say downtown St. Louis needs protection. It’s pre-existing infrastructure that’s concentrated in high in value. But Chesterfield Valley, Monarch Valley, if I remember some of these floodplain areas, they were sparse to nil infrastructure that was underwater in 1993, that now has again, it’s hundreds of millions, if not billions of dollars in place at residual risk of flooding today.

Dean Klinkenberg 42:27

Right. And we paid for the levee that made it possible. It’s our gift to Chesterfield. Right. So how in your ideal world, like, how would that process have played out differently to discourage that or stop it? Or what questions should have been asked at that time that really weren’t that asked?

Nicholas Pinter 42:49

Yeah, so I mean, this is often it’s a real tension. So I mean, you’ve got local interests. Landowners and developers and politicians often at the center of that, who want that protection, who want area to develop in a floodplain. For a big box store, it is the most beautiful place in the world to build. It’s flat, it’s often sand rich, good foundation. The landowner again, can see a huge tenfold, even much more increase in the value of their land. It’s ironic, that it’s often the taxpayer, you know, on people from completely other areas federal taxpayer often is footing the bill for what are mostly local and often massive windfall profits developed, derived from these projects.

Dean Klinkenberg 43:41

Right. That’s certainly seem to be the case out in Chesterfield. You and I helped pay for that but I don’t think we got a share of the profits from the last time I checked my bank account. But how do we like, this is one of the things I’ve been thinking about lately, too, in terms of navigation, infrastructure, as well as like struggling with this idea of the economic way we define economic benefits of big projects like this, and we allocate huge amounts of public money. Should we be thinking more about public benefit and not just general economic benefits from these projects? If we’re going to use federal tax dollars, particularly.

Nicholas Pinter 44:21

Yeah, so people are thinking about that. People smarter with a more stronger economics background than I. So originally Corps projects. So talk to someone else get the acronyms right, but I think it was the principles and guidelines that originally were the were the actual rules that govern whether these projects were approved and funded or not. And they were driven by simply economic development. It’s a purely economic calculation. And then I believe it was during the Biden administration, people said, well, this is ignoring the ecological harm, the potential ecological benefits of other alternatives. So let’s come up with a more nuanced approach to do that. And it was incredibly hard. So, so I appreciate, I appreciate the simplicity of a purely economic calculation, but it’s clearly it’s an equation with far too few terms. So we know we need a better way to do it. It’s just it is really hard. And people have struggled with coming up with that equation.

Dean Klinkenberg 45:29

And even as general Galloway said, in our conversation, too, there’s some things you just can’t assign a dollar value to, but they still have to be factored in. There’s no universal agreement on how best to do that. What’s the value of having a place for you know, egrets to reproduce and nest, and there’s no dollar value you’re going to assign to that.

Nicholas Pinter 45:52

Which doesn’t stop an economist from slapping a dollar value on that, right? I mean, yeah, so those ecological intangibles have been really, really thorny. And now we’re trying to put, you know, equity, equality, diversity into these equations as well. Again, worthy issues, but really, really hard to quantify, really hard to factor into these calculations.

Dean Klinkenberg 46:18

So at the same public meeting I mentioned, The High Water meeting with the with the Corps a couple of years ago, there was a person who, in talking about the pushback from environmentalists on levees. He said something I wrote down because I think it neatly encapsulates the way people tend to think about this. He said, we’re fighting for a way of life, they’re fighting for wildlife. And I understand that point of view, but I wonder like, there, there are many ways to frame this, what’s going on. And that’s only one and I think it’s probably not really a helpful way to frame it. How would you reframe that? Or how would you understand what we’re trying to do here?

Nicholas Pinter 47:09

Right, so that dichotomy is a false one. So first of all, credit to that speaker. Economic considerations, livelihoods should not be removed from this equation. They just have to be balanced with other things. And oftentimes, they are not irreconcilable. So again, we talked about multiple case studies where agricultural use in particular. So keeping in an urbanized area allowing floodwaters to get into an urbanized area, that’s kind of antithetical, right? But a piece of farmland, it’s okay. So it gets flooded one time in 100 years let’s say. That’s not the end of that farming operation. People may not be happy that year, the film crews…so this is Tulare Lake in California this year, film crews will show up and and and talk about the hardships of local residents and landowners. But really the long term viability of that farming operation on that acre of land is is not really reversed or removed by making, by reconciling with occasional inundation.

Dean Klinkenberg 48:23

Right. So part of it is understanding that, you know, it doesn’t have to be an absolute, right? An occasional high water event isn’t going to take away a person’s livelihood who’s farming? Whereas you know that a same a similar high water event in a densely populated area would probably take some lives. I guess I struggle too with this, this idea, that somehow even the wildlife or the river’s ecology aren’t worth protecting. And from your the work that you’ve done along the Mississippi, around the world, how do you think about the value of that aspect of things?

Nicholas Pinter 49:07

I personally value it quite a bit. I think landowners and farmers should value it as well. And we agree that it’s difficult to quantify, which does not mean that it’s not valuable.

Dean Klinkenberg 49:20

Right. Right. You think we’re gonna be doing anything different with levees here in the next couple decades? Or what do you what do you see going on?

Nicholas Pinter 49:31

So I’m sighing. So, look, there’s there’s room for optimism there. We talked about these case study projects where levees are actually being set back. Floodplains are being reconnected, good things are coming out of that. I’m pretty sure this Cosumnes River in the Sacramento area. There were large areas that did not breach their levees because they were set back decades now earlier. So reasons for optimism. But then you look at other places like Fargo, North Dakota which is now taking in hundreds of millions of dollars of federal money to deconnect, disconnect something like 50 to 70 square miles of floodplain and open it up to suburban development. So we talked about after the ’93 flood in your area, you know one step forward, but then two giant steps back all in one fell swoop, it’s harder to be optimistic looking at giant reverse steps like Fargo.

Dean Klinkenberg 50:36

Right. It’s this is so inseparable from a lot of related issues, like you mentioned, like in Fargo like the they’re hardly like they’re they’re in a difficult area geographically because you know, it’s pretty flat. And it doesn’t take the Red River getting very high to create problems. But they’re also just trying to create more areas that they can build with the current suburban model, which is very problematic for many other reasons. And that’s another topic of another show as well. But yeah, but those are local officials who are pushing that and then with the help of their federal representatives are getting the money to make that possible. They could never afford to do that with local money.

Nicholas Pinter 51:18

Absolutely, absolutely not. That’s correct, because this is the Corps designing, implementing and then the politicians enabling things like that. And we studied Fargo. We’ve driven around the Fargo neighborhoods. Fargo has, we studied, we’ve modelled Fargo’s opportunities included densifying redeveloping its urban core – protected by current levee infrastructure. And it decided nah we don’t want to do that. We’re going to sprawl, sprawl across tens of square miles of surrounding floodplain land.

Dean Klinkenberg 51:52

Well, and that project is underway now. I think, right? They started digging this year, I think.

Nicholas Pinter 51:57

Well underway there.

Dean Klinkenberg 52:00

Well, I don’t want to end on a dystopian note or anything like that. What, tell me like, what are some of the things that you have taken from being along rivers? What is it you like and enjoy about spending time along rivers?

Nicholas Pinter 52:19

Yeah, so, you know, rivers are the circulatory system of the entire landscape. So there’s, there’s, it’s no coincidence that the early European settlers across the Midwest really followed the rivers for navigation, for access, for water supply. I think also for scenery and livelihoods as well. And many of those values still exist. So I love visiting St. Louis. I love working on rivers. I’m, you know, we’re headed to Pajaro tomorrow. There are benefits to being there. But you have to be aware of the natural dynamics, and that is that includes occasional flooding. And occasional can mean a lot of different things. And plan appropriately for that. So really, I think everyone agrees it’s all about planning and avoiding the issues ahead of time. That it’s 100 times more difficult to unwind the mistakes of the past and avoid making them for the future.

Dean Klinkenberg 53:27

Absolutely. And I think that’s a great place to end this conversation today. Is there a place where people can follow your work that you would refer them to? Are you active on social media or have another place where they can follow what you’re up to?

Nicholas Pinter 53:39

Yeah, so the first I mean, different places. One place to go is the UC Davis Center for Watershed Sciences runs the California Water blog. Anytime we have something sort of fun. Interesting. We post it up there. So our levees, three part levee sniff test is published there and only there. Take a look search on the archives. There’s some good stuff in there.

Dean Klinkenberg 54:03

All right. I’ll post the link to that in the show notes as well. And thank you so much for your time. I appreciate it and keep up the good work.

Dean Klinkenberg 54:20

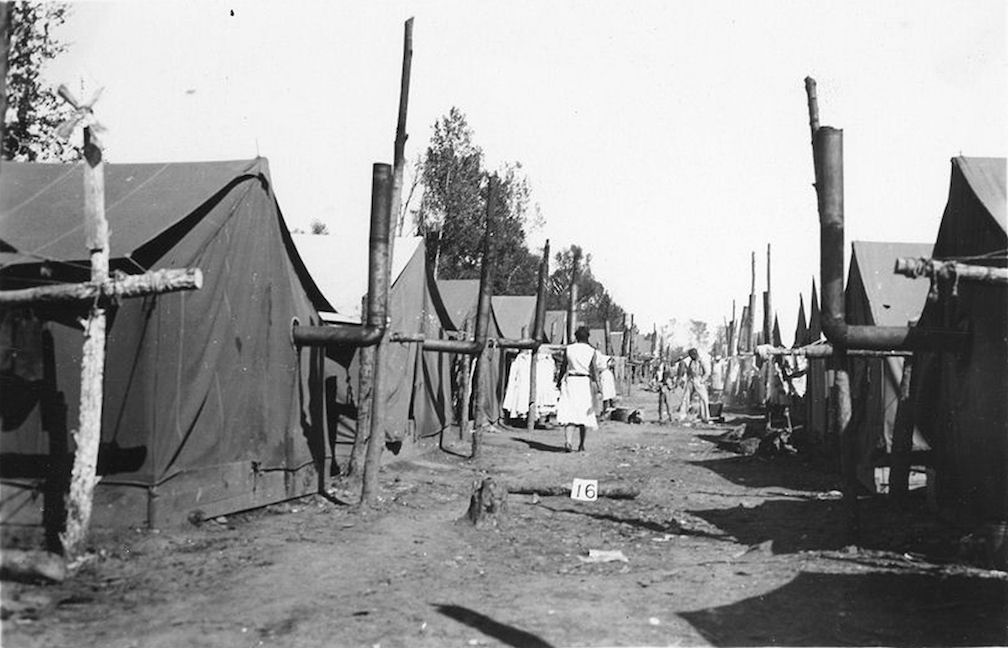

And now it’s time for the Mississippi minute. Levees are tall earthen berms built from dirt excavated near the river and piled up in a very precise way. Someone had to move all that dirt. Before the Civil War, most of it was carried and placed by enslaved Africans, although some work crews in Louisiana employed Irish immigrants too. After the Civil War, governments and local levee districts hired contractors to build levees because they didn’t have much machinery at the time they needed thousands of men and hundreds of mules. Many of the levee workers were farmers out to earn some extra cash during their offseason. Some were itinerant laborers while others were men who had served time in prison. Most were black. During levee construction workers didn’t have the luxury of commuting from home to work and back. So the levee contractors built camps where the workers lived during construction season. The camps weren’t viewed favorably by many people. In 1900, John Matthews floated down the Illinois and Mississippi Rivers in a shantyboat. In his book about the experience The Log of the Easy Way, he wrote, “We have been very fortunate so far in avoiding the levee camps along the river. Gambling and drinking and quarreling pass away the idle hours and murders are common occurrences.” Men lived in the camps for weeks or months at a time. The camps had reputations for violence and vice, perhaps because the white bosses encouraged a certain amount of lawlessness among among its workforce while keeping the police away. After all, encouraging workers to throw away their money on gambling, drinking and prostitutes was one way to keep them poor and indebted to the boss. Blues star Big Bill Broonzy commented that he once heard a boss say, if you boys keep out the grave, I’ll keep you out of jail. Living conditions in the camps ranged from substandard to appalling. In 1929, inspectors from the Public Health Service reported that camps for black levee workers the majority of the workforce at the 65 camps lacked outhouses. The men instead used open pits. Tents were tattered and poorly screened and had dirt floors. White levee workers were rarely forced to endure conditions like that. Big Joe Williams recalled – the life was hard. The men worked from sunrise to sunset. At night they slept in filthy tents on rotten mattresses with a couple of blankets to crawl under. The food just about kept a man alive. We had black eyed peas for supper for breakfast for dinner. And what y’all call corn bread and salt pork meat. That’s all we had to eat. He just throw it in the pot and you know y’all come and get it. That’s all. Building levees was tough, tiring and repetitious. The same heavy lifting repeated over and over throughout a 12 hour shift, interrupted only by a quick lunch break. A single white foreman might oversee 100 black workers, contractors use force to keep the workers on time and busy. At one camp a foreman welcomed all new hires with a beating. William Hemphill, an engineer from New York who worked in the Yazoo Mississippi Delta district in 1904, wrote, “if one of the white foreman shoots a couple of black men on the works, and by no means isn’t unheard of or infrequent thing, the work is not stopped. They’re buried at night. And that’s all there is to it.” Henry Truvillian, a levee camp veteran and blues musician, said that contractor Isom Lawrence killed more men up and down the Mississippi than the flu. Levee workers were paid about $1 a day for basic labor up to $1.50 a day if they could drive a tractor. That translates to about $7 to $10.50 per week, or about half the US average wage for manufacturing jobs at the time. That wasn’t take home pay though. Most companies deducted daily fees for food, water and sleeping in those luxurious tents. Bosses often delayed paying the workers sometimes for a month or more. So the men will be forced to borrow money from the company at interest rates as high as 25%. At the end of a four month stint, many workers left with just a few dollars in their pockets. In a 1932 investigation for the NAACP, Roy Wilkins wrote, “The levee work while it provides the much desired cash money. It actually delivers no more than the plantation owner. It is no exaggeration to state that the conditions under which negros work and the federally financed and Mississippi levee construction camps approximate virtual slavery.” Much of the levee work was financed by the federal government and overseen by the US Army Corps of Engineers. Wilkins accused the Corps of complicity in the maltreatment of black workers. The War Department, the Army Corps of Engineers knows all about this exploitation on the river. It knows all about the long hours, the low pay, the commissaries, the beatings, the living conditions in the camps, and in every camp there lives a war department engineer. The flag of the United States floats above his tent and over the sweating back of the free black citizens who swear allegiance to it. The workers did get some downtime, usually Saturday night and Sunday,a popular time to visit a juke joint in the camp. The juke joints could be wild places. Gambling and fighting were common. Maybe the only place the man had a chance to be free and human, even if that meant taking things to an extreme at times. Toughest places I’ve ever seen was some of them honky tonks, call them barrel houses and Charlie Loran’s camps, Big Bill Broonzy told Alan Lomax. So, popular blues musicians played those juke joints. Some, like Big Bill Broonzy had worked there too. Maybe that’s one reason there’s so many songs about levee camps. If you were a black man in the south during that era, you probably worked in a levee camp at one time. Especially if you’re from the Delta. It was just part of life, like love, poverty and hard times. As levee work became more mechanized, The need for hundreds of laborers and camps to house them diminish. Levee construction today is completed with heavy machinery and a handful of men. The Corp’s mat sinking unit employs three boats and just a few dozen men delay hundreds of thousands of sheets of articulated concrete mats along the rivers banks to prevent erosion. Tractors and earthmovers push and compact dirt to raise the levees higher. The foundation of those modern embankments, though, is the old levees built from the toil of thousands of men who were paid next to nothing for their labor. There are at least a dozen songs that documented the experience of working and living camps such as Levee Camp Holler. It’s a good one. John Cowley wrote a good summary of them in an article called Shack Bullies and Levee Contractors. There are also some good songs about the plight of flood survivors living in temporary camps on the levees. I like Alice Pearson’s Greenville Levee Blues. I’ve put together a playlist in Spotify. It’s got about 15 songs all about levees and the camp experience. I’ll post a link to it in the show notes at MississippiValleyTraveler.com/podcast. Do you have any favorite songs about levees yourself? Drop me a note at MississippiValley Traveler.com/contact.

Dean Klinkenberg 1:01:27

Dean, thank you.

Dean Klinkenberg 1:01:45

Thanks for listening. If you enjoyed this episode, subscribe to the series on your favorite podcast app so you don’t miss out on future episodes. I offer the podcast for free but when you support the show with a few bucks through Patreon, you helped keep the program going. Just go to patreon.com/DeanKlinkenberg. If you want to know more about the Mississippi River, check out my books. I write the Mississippi Valley Traveler guide books for people who want to get to know the Mississippi better. I also write the Frank Dodge mystery series set at certain places along the river. Find them wherever books are sold. The Mississippi Valley Traveler podcast is written and produced by me Dean Klinkenberg. Original Music by Noah Fence. See you next time.