What’s it like to work on a riverboat? Lee Hendrix entered riverboat work in 1972 as a deckhand, worked his way up to mate, then into the pilothouse. He has spent most of his adult life as a pilot of riverboats big and small, from tows pushing barges to elegant overnight cruise ships.

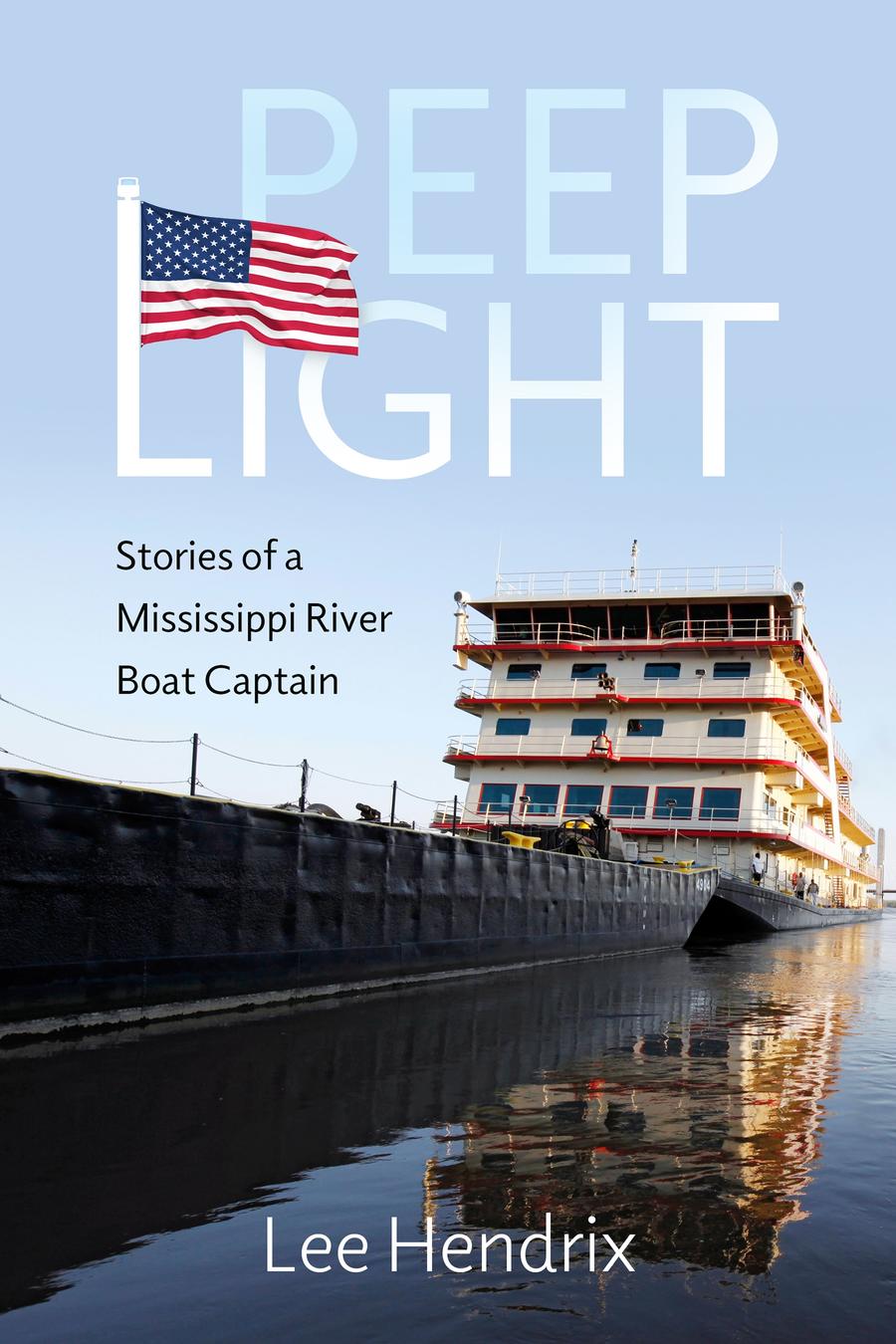

In his new book, Peep Light: Stories of a Mississippi River Boat Captain, Lee shares stories from those years on the river. In this interview, we talk about how he got his start working on the river, the grueling but satisfying work of a deckhand, and the jobs on a towboat. We also discuss his path to the pilothouse, the basics of steering a tow pushing a load of barges, and the differences between piloting big and small boats. Near the end, Lee talks about the allure of river life and the long, sometimes lonely life of working on a towboat.

In the Mississippi Minute, I offer a few tips for paddling on the Mississippi River around commercial and recreational boat traffic.

Show Notes

Tips on paddling on the Mississippi River around commercial and recreational boats:

- https://mississippiriverwatertrail.org/safety/

- https://www.rivergator.org/river-log/stlouis-to-caruthersville/stl-car-appendix/pg/3/

Photos of Lee Hendrix, author of Peep Light: Stories of a Mississippi River Boat Captain

Support the Show

If you are enjoying the podcast, please consider showing your support by making a one-time contribution or by supporting as a regular contributor through Patreon. Every dollar you contribute makes it possible for me to continue sharing stories about America’s Greatest River.

Don’t want to deal with Patreon? No worries. You can show some love by buying me a coffee (which I drink a lot of!). Just click on the link below.

Transcript

Wed, Jan 24, 2024 8:09PM • 1:14:04

SUMMARY KEYWORDS

river, boat, pilot, work, tow, barges, mississippi, bridge, deckhand, mississippi river, chart, stories, years, called, book, podcast, rudders, people, paddlers, long

SPEAKERS

Lee Hendrix, Dean Klinkenberg

Lee Hendrix 00:00

We were coming up Grand Tower Chute. And the pilot called me up and he said, “I gotta go to the bathroom, you know how to steer it?”, which I didn’t know at all. And I said, I didn’t want to seem stupid, so I said, “Yeah, go ahead.” And so I, this boat had these air controls so it didn’t it wasn’t like a follow up system. So wherever you push the sticks wasn’t exactly where the rudders were, and I had no earthly idea about what I was supposed to be doing. And I just thought to myself, I sure hope he gets his business done quick, because I don’t want to bust this toe up on this sandbar, run up one of these people in these boats. Luckily he came back up. And I said whoa, next time I better learn a little bit more before I for a volunteer to do so.

Dean Klinkenberg 01:21

Welcome to the Mississippi Valley Traveler Podcast. I’m Dean Klinkenberg and I’ve been exploring the deep history and rich culture of the people in places along America’s greatest river, the Mississippi, since 2007. Join me as I go deep into the characters and places along the river and occasionally wander into other stories from the Midwest and other rivers. Read the episode show notes and get more information on the Mississippi at MississippiValleyTraveler.com. Let’s get going. Welcome to Episode 33 of the Mississippi Valley Traveler Podcast. We are back for 2024 after a much needed break. I got to spend a little time traveling at the end of last year. Spent a couple of weeks in Costa Rica. Really enjoyed that. Got to take a river tour. If you are curious or want to see any of the photos from my trip down to Costa Rica check out my Instagram feed, that’s probably the best place to go, which is just Dean.Klink. On our river tour, I got to see three different species of monkeys, lots of birds, and a type of lizard called a basilisk that I wasn’t familiar with. Just a fantastic tour made me think so much of the possibilities of nature travel along the Mississippi as well. I’ve also been working a little bit on an exhibit on my family history that’s been taking up a lot of time. When my my father knew that he would be passing away soon he asked me to coordinate this and put together an exhibit about our Klinkenberg family history for the museum and the town where he grew up. So I’ve been putting a lot of time into that. And that seems to be about done. And I’m ready to put my energies back into the podcast. I’ve got big plans for this year, we’re going to have several authors on. I’m going to be doing a lot of reading this year, including a couple of authors that have new books coming out this year that I’m really excited to read and to talk with the authors about. In addition to that my new book, “The Wild Mississippi” will be out in May, on May 21. And around that time I’ll start rolling out episodes that will highlight different aspects of the natural world of the Mississippi. If you are interested in preordering that book, it is available right now. Just go to the usual marketplaces, look up “The Wild Mississippi: A State-by-State Guide To The River’s Natural Wonders”. And you can find it everywhere you might buy a book. Well, let’s get on to this episode. We’re going to kick off this year with one of the authors who has a new book coming out. Lee Hendrix spent much of his adult life working on the river and he just released a book called “Peep Light”, that’s a collection of stories from that long career on the river. He started as a deckhand in 1972 and worked his way up to the pilot house just a few years later, and spent much of his adult career as a pilot on on boats big and small toes pushing barges, passenger ships, even the the biggest tow boat in the world, the MV Mississippi. So in between he took a little bit of a break to work as an outdoor educator. In this episode though, we talked mostly about his experience working on the boat starting as a deckhand. What was that like? What’s the life of a deckhand like? And moving to a discussion of how he managed to climb the ladder into the pilot house and what it’s like to to be the one behind the wheel of those massive boats as they make their way up or down the river. We talk a little bit about the different jobs on the whole boat and a close call that he had as a pilot, and a few impressions about working on the river. Again, his book is called “Peep Light: Stories of a Mississippi River Boat Captain”. And when this episode releases, that book should be available anywhere you shop for books. As usual, thanks to all of you who show me some love through Patreon. Your support makes this podcast possible it keeps it going. I am so grateful for it. Working on making a few changes this year, mostly to increase the value to those of you who do subscribe through Patreon. One of those things I’m committed to doing this year is early release. So getting myself a little more organized. So I can have the episodes out a couple of days before general release so Patreon subscribers can listen early. So if you’re interested in joining the Patreon community, just go to patreon.com/DeanKlinkenberg and you will find out how to do it there. If Patreon is not your thing, well, you can buy me a coffee. It’s a one time contribution to show some support for the podcast and help me sustain my coffee habit. Greatly appreciate it as well. And you can do that just go to MississippiValleyTraveler.com/podcasts and you’ll find out how to do it. And now on to the interview. Lee Hendrix began working on the Mississippi in 1972 as a towboat deckhand and just four years later, he became a pilot. He took a sabbatical from river life in the mid 1980s, working in Europe for an outdoor education center, then came back to the US and worked with the Student Leadership Environmental Adventure Program or S.L.E.A.P. in the St. Louis Public School system. During his years there, he got married, had a family, worked for the North Carolina Outward Bound school and earned a master’s degree in communications from Webster University. Lee never left the river that flows within him though and sought part time work as a pilot in St. Louis. He later became a captain of passenger vessels and casinos in the Midwest. In 1994, he went to work on passenger steamers, the American Mississippi and Delta Queens. During that period, Lee also began writing stories for Big River Magazine in Winona, Minnesota. And he’s also had stories published by the St. Louis Post Dispatch and the Waterways Journal. In 2009, Lee went to work for the US Army Corps of Engineers on the MV Mississippi, the largest river tow boat in the world. He retired from the Corps in 2018. Since then, he’s done trip work for several years and dabbled in writing for a living. Currently, he works on the American Queen as River Laureate. When off the boat, he spends most of his time writing and walking his black lab, Charlie, with his wife Diane, around Lake City, Minnesota. And one of the main motivators for having him on the podcast today is he’s also the author of the forthcoming memoir “Peep Light”, which contains a collection of stories from his years working on the river. Welcome to the podcast, Lee.

Lee Hendrix 08:10

Thank you, Dean. Pleasure to be here.

Dean Klinkenberg 08:14

So let’s kind of start with little bit of background on the book itself. The book is a collection of essays, as I mentioned, and some of them looks like you wrote quite a few years ago. So I’m kind of curious, like, when did you start writing about your time on the river? And what was your first piece?

Lee Hendrix 08:31

I can’t really remember when the first one was. But it was about 30 years ago, I would say in the mid 1990s. I was back in St. Louis, although of that one about Jimmy Dan, the ghosts boat down around Old River Control structure, I might have actually started that in the 1970s. I know that the inspiration for it came up right out of the 1970s because I was a young pilot and I was just scared to death. We didn’t have electronic charts back in those days. And fortunately for me, there was other young pilots out there too, who are also scared to death. So sometimes, at night, we’d go over to other channels and talk about some of the things that really scared us about the river. And I just kind of put all that together. That story and Splicin’ Line about pappy teaching me how to splice line, and Lock on the Head, those are all stories that I wrote in the 1990s or earlier.

Dean Klinkenberg 09:48

What sparked that interest in writing about your experiences?

Lee Hendrix 09:52

Well, you know, I said when I started on the river in 1972 I just I was like a stranger in a strange land. I was like I’ve been transported into a cowboy movie or something. And I got on the boat. And the guys didn’t know quite what to think about me because I didn’t really know anything about what was going on. They had a, they had a name for me. And I’ll give you the acronym because I don’t want to insult any of the listeners right away, I’ll just give you the acronym. They called me a D, M, F. And the D stood for dumb. And you can kind of figure out on your own what, what the rest of it meant. But I remember going home and telling some of my friends stories about what had happened. And it was like I was transporting them into a different world. I told this one friend of mine one night at a party that a guy, a pilot broke his tow. And she said, well, didn’t they take him to the hospital didn’t that hurt. She thought he was talking about his big great toe, or something like that. And I just felt like I was had become part of this very arcane lifestyle that people, even though people even here in Lake City, and I’m looking right out over Lake Pepin right now. So we have tow boats go by here all the time. But yet, so many of the people I know around here, they asked me questions, and I realized they don’t know anything about what they’re seeing. And I just thought that I would try to my mission in life now is to try to let people know exactly what it is that we do out here. And the feelings that we have about what we do.

Dean Klinkenberg 12:00

Well, I think I thought your book that a really fantastic job of that. It was it was a lot of fun to read. The stories are very interesting. I imagine you held back some stories that you either couldn’t tell or didn’t want to tell in a book like this. But it’s really an interesting read, and especially for people who are interested in getting a little bit of a peek behind the curtain of what it’s like to work on the boats that travel along the river. So I want to thank you for that. And let’s, let’s kind of go back then, like how to how did you get started working on the river in the first place? It’s not like you came from a family with a long tradition of river people as I remember it.

Lee Hendrix 12:39

No, my father was on a ship in World War Two. And actually, he tried to talk me out of going on the river, because he said, “You’re not going to like it. You’re not going to like the food. It’s going to be claustrophobic. You’re not going to have your dog with you.” He tried every trick in the book to try to get me not to go but I had I wasn’t a star in school. I wasn’t like a star football player or I did wasn’t the valedictorian. I didn’t have a whole lot going on for me. And I went to a party one night and I was talking to this fellow and he said he had worked on a on a tow boat, and he didn’t even call it a tow but he called it a riverboat. And he had saved up enough money to go on a trip to Europe. And I didn’t have enough money to go to Europe, although I wanted to go and I thought well, that might be kind of a template for me to follow. I’ll try that. And of course St. Louis at the time was the nexus of, it was ground zero for the towboat industry back then. And just went to some offices down in Clayton. And finally, a towing company called me not I didn’t know what towing meant, I thought that was like a tow truck on the river. I had no earthly idea about why how that could all come together how you could have a tow truck on the river, but I was determined to at least find out.

Dean Klinkenberg 14:17

And then so you got hired and what they sent you to a school somewhere for six months of training, right? Oh, no,no, no, no, no, no, not that. Not in them days. The guy called me and he said, “You still want a deckhands job?” And I said “Sure, yeah.” I thought he was giving me about a week to back out of it. And I said “Where where do you want me to go?” and he said, “Well go to the Missouri Portland Cement Dock on Riverview Boulevard.” And then I said, “When do you want me?”, thinking it would be like next week or the week after he said, “Be there at five o’clock tonight.” So I really had no time to check out of it. It was, it was like Robert Johnson, I brought myself to the crossroads. So how long were you on the river for that very first assignment, then?

Lee Hendrix 15:11

Oh, I think I was on there about 40 some odd days. Because, you know, the longer you stay out there, the more money you make, obviously, and you’re not spending any money when you’re out there. So I think I did actually make it 43 days that first time. 30 days would be the, if there is a normal, that would be the normal one. But now some of them go to like, weekly crew changes, so it’d be days divisible by seven, like 28 or 21. Something like that.

Dean Klinkenberg 15:51

So alright, so you, you have just a few hours to get yourself together and get down to this dock. What did you, what did you quickly discover about this work once you were kind of hanging out down there?

Lee Hendrix 16:05

The boat is never on time. I told you to be there at five o’clock. So I got there a little bit before five because I didn’t want to be late. And there was a couple of fellas down there loading cement barges and I strolled down there and I said, “I’m here to catch the Van Zephyr it’s going to be here at five.” And they kind of chuckled, and said, “It ain’t gona be here at five, who told you that?” I said, “Both of them. A guy in the office did.” They said, “Son, let’s sit down here and let’s talk for a little bit.” We smoked some cigarettes for a while and my dad would come back and forth. He was hanging out at a beer joint. And he would come back in his ’55 Chevy and we drive around and he was steady trying to talk me out of this adventure. And about eight or nine o’clock that night I was starting to think maybe he was right, because the boat still hadn’t showed up. And 10:30 I was about ready to give it up and go back home, and I saw the search light down the river coming up the river. And the rest, as they say is history.

Dean Klinkenberg 17:15

So what was the work routine like as a deckhand?

Lee Hendrix 17:20

Well, it’s funny, because when I got on the boat, guy took me back to my room and he said, “Well, you get to sleep. You get to start your river career in bed.” And I thought, well, that sounds pretty, pretty decent, pretty civil. But the problem with that, that he didn’t really go any further about was I couldn’t sleep because I was so scared. I was afraid that the bulkhead of that boat was going to come caving in and the Mississippi River was going to drown me in my bunk the first night. So I really thought the mission the first night was to kill Lee Hendrix. But they didn’t succeed in that. Got up the next morning I was what’s on what was called the front watch, the forward watch. And our duties consisted of putting barges together and do a tow catching lines in a lock. Cleaning up the galley, cleaning up the pilothouse, making the captain’s bed. So a lot of maid service kinds of things. But the main reason you were on there was to lift heavy things, and put barges together and to occasionally mop decks and that kind of stuff.

Dean Klinkenberg 18:46

One of the interesting things you mentioned in the book was that at the time you got on the river, like almost all of the deckhands came from just about two or three counties, mostly from Kentucky. Could you talk a little bit about that? Like who was working as a as a deckhand at that point in time? And what did it take to be a deckhand?

Lee Hendrix 19:04

So when I got on that night, I climbed down the ladder into the mystery below. And there was a fellow about my age. And he kind of looked at me up and down and he said, “What part of Breckinridge county you from?” And I was taken completely by surprise, I said, “I have no idea where that even is.” And he turned and spit on the deck and said “Damn, we got us, we got us a renegade here.” All of the deckhands on that particular boat were from either Breckenridge or Meade County in Kentucky. And they would get hired out of this beer joint. It was called Dead Horse Holler, and one of the captains would go in there and hire the crew out of the beer joint and he hit, he raised hogs and if you had some hogs to sell him, you would be more likely to get a job. So I was definitely the sui generis in that in that whole milieu when I first started. But yeah, I would say on that boat 80% of the guys came from either Breckenridge or Meade County. Now a lot of them lived in Breckinridge County, which was a dry county. So they had dry counties then and they would go over to Meade County, which was a wet county to go to Dead Horse Holler. So that’s, that was that’s that back in those days, that was fairly typical. I guess the reason they got me on was maybe somebody quit, or maybe somebody fell overboard? I don’t know. But they needed a deck and real quick. And I was in St. Louis, and I just happened to be handy.

Dean Klinkenberg 20:55

Well, so I guess if you were living in Breckenridge County, you had to be a little careful about where you went out for a drink. Otherwise, you might find yourself working on a towboat the next day,

Lee Hendrix 21:04

And you could very well yeah, but that was one of the that was one of the sought after jobs there was to was to work on a towboat. That was a real towboat culture there.

Dean Klinkenberg 21:15

So I imagine stories like this must give, like personnel directors or HR departments, nightmares today. But like, basically at that point in time, you could be pretty anonymous, as you wrote, you could basically be pretty anonymous, and get hired on the towboats and just sort of slip into two river work.

Lee Hendrix 21:36

Oh, yeah. And it depended on the company you work for now. The company I worked for was originally was in terms of their professional stance, probably toward the toward the better end. But some of the companies I’ve worked with over the years, you met some people who you felt like it was not really appropriate to dig too much into their past. It was kind of like, you were in the Foreign Legion. There you’re not, you know, somebody wants to tell you about their past. It’s okay. But you don’t wasn’t considered to be fair game to start asking people about where they come from. And as it went on, when you’re on a boat with, with people long enough, you you do develop a sense of trust, or maybe it’s just boredom, and figure well, I’ll tell you about it. And they weren’t the, some of them had some very sordid pasts. I’ve worked with some murderers, with some abusive people, and I’ve also worked with some deacons in church. Everything from pimps to preachers as Paul Thorne, a musician I’ve listened to, says. It’s a lot of good stories, a lot of rich material.

Dean Klinkenberg 23:16

Absolutely. So I guess like if one was going to apply for a deckhand job today, there’d be a little bit more rigorous background check.

Lee Hendrix 23:26

Oh, yeah, it’s a much different game today. You know, you can’t you can’t get a job at a Quick Trip anymore without going through two weeks of paperwork. So yeah, they’ll investigate your background. Now, there are still some companies though, who, who hire out of prisons. And I won’t mention any names, but they find that people who’ve done time do quite well on towboats because there it seems like freedom to them, even though it it seems like prison to most of us to them it’s like, oh, wow, this is pretty good. I got I kind of got the room to myself here for a while.

Dean Klinkenberg 24:14

And I get to go places.

Lee Hendrix 24:15

Except you can’t get off. You’re a prisoner on towboats. Now, they won’t let you get off when you get to town anyplace.

Dean Klinkenberg 24:26

So when you, maybe at some point, you must have started thinking about like how long you wanted to work on the river and what kind of jobs were available to you? Like, what, when you began thinking about like the longer term, were there certain kinds of jobs that you were angling for, or trying to work toward?

Lee Hendrix 24:49

Well, I never was real mechanically inclined. So working down in the engine room didn’t really seem like a good fit for me. I really loved working on the deck and becoming a mate. I liked going outside, at least when the weather was nice I did, and putting barges together. But if you’re going to stay out there, most people either choose to get a job in the engine room or they go go to the pilot house because that’s where you’re going to get paid more money. And you don’t find too many deckhands over about 35 years old or you didn’t back in those days. And even today, not too much, because the work is so physically strenuous, and and dangerous as well. So I kind of made up my mind that I at least wanted to try to become a pilot. And like I said in the book, it wasn’t because of my brilliance. But it was because they really needed pilots badly back in the 1970s, because of industry expansion. So I kind of had my sights set on that.

Dean Klinkenberg 26:09

So I sometimes get confused about this too. And maybe some of the listeners are like me in this regard, the terms that we use for the different jobs on a boat, let’s just kind of start with the towboat, you just mentioned a mate. So like if you’re what’s the basic job structure and hierarchy on a towboat?

Lee Hendrix 26:28

Now some of those have changed a little bit over the years. But when I first started, you had deckhands, which I was one, and you mopped decks and picked up heavy things and caught lines and did all the grunt work of putting the tow together and keeping the boat clean. And normally you would have a mate who was sort of the foreman of the deck crew. So a good mate would go out there with the deck crew and work right alongside of them. But he was he was the boss. He was the one lighting the trail for you, telling you what to do, where to go, how to lay that particular wire. Then there was two people worked in the engine room. And now sometimes they would also have what was called lead man on the deck. So sometimes that was interchangeable with with the mate. In the in the engine room back then we had a chief engineer who’s responsible for keeping all the engines the main engines running, but also responsible for the maintenance of the plumbing systems, electrical systems and everything you got to take care of in your house, you know if a refrigerator goes out or if the air conditioner goes out, or if the toilets go up. That would be the chief engineer to make sure that they came that came about and back then he had an assistant called an Oiler, O-I-L-E R. And the oiler did was kind of like the deckhand for the chief, they wouldn’t work together. Normally they would work different watches, although if there was some special project they would, they would both work together on it. The oiler maintained the engines on the what was called the after watch, or the back watch. And the chief engineer normally worked the front watch. Then you had a pilot on the after watch, is responsible for navigation. And then the captain was the also a pilot on the forward watch. But in addition, the captain was responsible for the overall administration of the boat. Anybody needed to be disciplined or if the groceries needed to be ordered. The captain had to take care of all that. Back then we always had a cook on board. That’s pretty self explanatory. In addition to cooking, they were in charge of ordering groceries and yeah, that’s basically about what they were supposed to do. And then occasionally you would have a steersman, S-T-E-E-R-S-M-A-N, and the steersman was a pilot in training. So pilot or captain would take a deckhand or a mate who they thought might have some ability to someday become a pilot and stuck them up there behind the sticks and taught him taught them how to take the boat up and down the river. So that was basically the way it worked. Now today, there’s been a one of the unfortunate things about the industry is they’ve tried to cut back on human beings. So very often you only have one engineer instead of two. Some boats don’t have cooks. So you have a deckhand or somebody. It’s kind of a free-for-all about cooking. And some of the deck crew has been cut back and now the mate, the way the license structure is set up, a mate is kind of like a pilot legally with the way the Coast Guard views it. Although most towboats, they still call the navigator on the back watch, the pilot.

Dean Klinkenberg 30:35

Hey, Dean Klinkenberg here interrupting myself. Just wanted to remind you that if you’d like to know more about the Mississippi River, check out my books. I write the Mississippi Valley Travel guide books for people who want to get to know the river better. I also write the Frank Dodge mystery series set in certain places along the Mississippi. Read those books to find out how many different ways my protagonist Frank Dodge can get into trouble. My newest book, “Mississippi River Mayhem” details some of the disasters and tragedies that happened along Old Man River. Find any of them wherever books are sold. So there’s a lot more complexity to those roles. And I think people would necessarily assume they’re not huge crews. It’s not like an ocean going cruise ship with, you know, hundreds of people working on it. So what was your path then to the pilot house? You worked as a deckhand for about four years, so how did you make the transition up to the pilot house from there?

Lee Hendrix 31:34

Well, I was a deckhand for a couple years, and then I got booted up to lead man and mate, and that was a mate for a couple of years, and met a pilot, Adrian Hargrove, who took a liking to me, and he got me back behind the sticks. And first day, it’s like, look, look up there, that tree up there, that house on that bluff, see if you can hold that jackstaff, which is the jackstaff is the pole at the end of the tow that tells you which way you’re swinging and see if you can hold that jackstaff on that house. You know, something very simple like that. Just see, if you can keep it straight, you know, five or 10 minutes, you know, oh, and maybe after a while they trust you enough where they go back to the bathroom or something and leave you up there to steer. Because we didn’t have toilets in the pilot house back then. And then you know, it’s just a great organic process, they’ll let you take it around a turn or you’re not scaring them too badly. To get through a bridge or meet another boat. It just happens kind of slowly. As you gain some confidence that this person is not going to wreck the tow you’re doing whatever you got, you got to do

Dean Klinkenberg 33:01

It’s a little bit of an apprenticeship, I guess, where they give you a little bit more responsibility each time you’re there.

Lee Hendrix 33:08

Yeah, I mean, you know it’s the consequences of having a boo boo were so great. You don’t want to you don’t want to stretch somebody out too much. You don’t want to put them out of their comfort zone and you don’t want to get out of your comfort zone either.

Dean Klinkenberg 33:23

So do you remember the first time you had control the boat, what that experience was like?

Lee Hendrix 33:28

Oh, yeah, yeah. So we were coming up Grand Tower Chute, and the pilot called me up and he said,”I gotta go to the bathroom, you know how to steer it?” Which I didn’t know at all. And I said I didn’t want to seem stupid. So I said, “Yeah, go ahead.” And so I this boat had these air controls, so it didn’t it wasn’t like a follow up system. So wherever you push the sticks wasn’t exactly where the where the rudders were, and I had no earthly idea about what I was supposed to be doing. And I just thought to myself, I sure hope he gets his business done quick, because I don’t want to bust this tow up on this sandbar and run over one of these people in these these boats. Luckily he came back up and I said, “Whoa, next time I better learn a little bit more before I before I volunteer to do something.”

Dean Klinkenberg 34:31

Do you suppose a pilot would give a rookie the same opportunity today?

Lee Hendrix 34:41

Depends on how bad you gotta go pee. You know, most of the pilot houses today have bathrooms up there. But when I became a pilot I am and I’m basically pretty lazy by nature. So if I can get somebody else to do my work that’s all so much the better. And if I can stick somebody up there to steer the boat for me, well, I don’t know, read a little bit or do a few pushups or walk around. I’m, I’m subject to do that, and, and let them have at it. It helps them because that’s a possible career path for them. Now, there’s a lot of older pilots who won’t do that because they see that person as someone who’s gonna take their job away. So they’d poop in their pants before they’d let somebody else steer the boat.

Dean Klinkenberg 35:45

Yeah, I don’t want to have to think too deeply about that one. But yeah, that would be one way to discourage the rest of the crew from hanging out in the pilot house I imagine.

Lee Hendrix 35:55

It would, yeah.

Dean Klinkenberg 35:58

So, so walk us through, like, I know, we could probably spend hours talking about this little piece of it, but just give us like a quick overview of how you navigate. What the tools are for navigation, but also how you steer and operate the tow itself.

Lee Hendrix 36:17

Well, so that’s changed a little bit over the years too, used to be you, every boat had steering and flanking rudders. So the steering rudders are two pieces of metal that are aft of the what we call the wheels, you might call them the propellers. And there’s usually one steering rudder behind each propeller, or wheel. And then there’s two flanking rudders forward of each of each wheel. And they’re situated on the console right in front of you, and you’ve got them off to the, to the side of you. And almost the whole time you’re, you’re working the steering rudders going up the river because you’re coming ahead and that’s what steers the boat, the steering rudders. Now, when you go to maneuver, or if you’re going downstream, sometimes you have to use your flanking rudders. Not nearly as often as you use the steering rudders. You’ve got searchlights, normally they’re on top of the pilot house, but sometimes, they’re off to the side of the pilot house that you use to see buoys and trees and things out, out in the river. So you’ll operate those. And then one of the key things that you have to learn how to do is talk to other boats. You have VHF radios to communicate with other towboats or with you know, whatever’s out there on the river, because you have to figure out a way to pass each other, or meet each other without running into one another. Is that basically, what you’re looking for?

Dean Klinkenberg 38:03

Yeah, and I know today you’ve got GPS maps and all that. But when you were starting on the river, you were using what, paper maps and buoys to kind of keep track of where you were or maybe your memory at times, too? But you didn’t have the GPS system in the 70s I assume?

Lee Hendrix 38:19

No, your memory had to be pretty honed. Um, we had paper charts. My friend John Duggar told me a story once about a guy who had talked his way into the pilot house and he didn’t really know where he was. And he had a paper chart. And he was, he only had one barge and he was coming behind down behind a big tow, and he finally got the gumption enough to to pass the tow. And he got around him and he realized he didn’t know where the hell he was, because he had been following Bird Dog and that other guy. And then right at that time, his his chart, this is two o’clock in the morning, it’s completely dark and his chart fell on the floor and then he reached over to pick the chart up and his coffee cup fell on the floor. So now he’s got to clean up his coffee cup and his chart and while he’s doing all that, his boat and his tow turn completely around, and he didn’t realize he was not going down river anymore, he’s going up river. And now he’s looking at the same boat that he just got around, thinking that somebody he’s going to meet still going down the river. And the guy said, “Hey, are you the one just got around me?” And Neckbone said, “Yeah, I guess I am.” And he decided that the best course of action then was to go get back behind that guy and no matter how slow that guy was going, he was just going to stay behind him because that guy had to know hell. a lot more about where he was than he did. So to make a long story short, roadmapping, which is what you call when you’re just using a paper chart was a very awkward thing to do particularly at night. Now today, it’s a lot easier to learn the river because you have a GPS and you have what’s called an AIS, an Automatic Identification System. So you not only know where you are on that chart, you know where everybody else is too. So you can make a plan about where you’re going to meet another another boat. So it’s, it’s a lot more automated now than it was back back when I started.

Dean Klinkenberg 40:48

You know, I was just thinking back when Mark Twain was a pilot and writing about his experiences on there, the river was a very different beast. They didn’t have maps to work with for one thing, and they had to have eyes on the river to spot sandbars and changes in the channel and that kind of thing. How much of that is still a concern for pilots today, like the river is much more managed? How much, do you need the maps that much? Like how important are those kinds of things today?

Lee Hendrix 41:23

Well, the charts are still important, not not so much from a standpoint of that the river is going to change, which doesn’t hardly at all anymore, because the Corps has been able to confine the river in the channel. So that’s not to say that as the river goes up and down, that you get a sandbar. One trip you might be able to run over the edge of a sandbar or maybe run right over the top of a sandbar if there’s enough water. And if you try that the next trip, you’ll you’ll run hard aground. But in terms of the channel going from one side of the river one week over to the other side the next week or on one side of an island today and and a different side tomorrow, no that that doesn’t happen. That’s all, that’s all 19th century stuff. And the other thing to remember about Mark Twain is he was only a pilot for two years. And if you read his books, you know he has a very vivid imagination. So he was out to sell books. Although I suspect that a lot of that probably was pretty true. You had to you had to pay it you had to keep it all in your in your memory, which you don’t need to do that quite so so vividly anymore, because the charts just right there for you. You can even pan the chart out 10, 15 miles to see what’s up ahead.

Dean Klinkenberg 42:59

Well, so let’s one of the things that jumped out at me too in reading your book was the wide variety of boats that you’ve piloted. You know, from towboats all the way up to the massive MV Mississippi to passenger boats. You probably have a jon boat you’ve driven boat recreationally to I imagine. What’s the how does the experience differ piloting those different river boats?

Lee Hendrix 43:26

Well, so one thing that really surprises people a lot is that it’s really just as hard to go from a big boat to a small boat as vice versa. People really find that to be surprising. But most people who have done both will, will tell you the same thing. Because when you’re on a big boat, it has such, it has so much mass, that it’ll track itself in a in a straight line or it’s got momentum, going to keep following a certain track. With a small boat it’s not nearly like that. You have to make it do everything. And everything happens really quickly. I got a job on a casino up here had a small little boat. And I just decided a couple years ago that I was going to try to stay home and work for a year. They found out I had a big license and that I piloted the American Queen and oh they expected I could I could turn that thing upside down and go into a dock with it. And they quickly found out that I wasn’t I wasn’t so I wasn’t so adept at handling that little boat because I just never done it before. And it reacted so much more quickly. So You know, like towboats, like I say, they’ve got the standard, most of them have the standard steering rudders and flanking rudders. But now some of the towboats have got Z-drives, which I became used to use them with the American Queen. And Z-drives are wheels that turn 360 degrees back toward the stern. And of course, the steamboats had a paddle wheel too. So you had a number of things to play with there, they had bow thrusters. Then I got to my last gig with the Corps was run on a small tender boat, I went from running the MV Mississippi, which is the biggest towboat in the world to run on this little boat that was about 40 feet long moving pipes around. And there again, there again, I made a fool of myself real quick the first couple of days with all those guys, because “Oh, that guy was the captain on the Mississippi, shoot man, he don’t look like he could land a jon boat on a dock.” So you know, every boat is gonna have its own idiosyncrasies that you’re going to have to get used to.

Dean Klinkenberg 46:18

So I have to ask you this question. So from the pilot house, which bridge is the most beautiful?

Lee Hendrix 46:25

Oh, there are no pretty bridges. I got a story there and there ain’t no party bridges. Beautiful, I don’t know. The wider ones are the most beautiful ones. Actually, those bridges down in Memphis, they’ve got these like psychedelic lights on there. Lights change shape and color. They’re really kind of cool. When you when you come down on you can you can put them out if you key your mic on a certain channel. That and then there’s some bridges up in Little Rock, the Arkansas River, that have have that going for them also.

Dean Klinkenberg 47:15

So what are what are some of the challenges about steering through between those piers?

Lee Hendrix 47:21

Well, they got a lot of bridges have got set on them. So you’ve got to make sure that you line up correctly for them. And of course the set will…every bridge is a little bit different. But the set will change at different river stages will become stronger, obviously the higher the river is. So you have to often hold one to appear a lot longer than then you would think that you might have to. The Vicksburg Bridge is in particular is one like that. So there was an old river pilot named “Womp O”, Edgar Allen Womp O, and somebody asked him one time “Well, how do you make that Vicksburg Bridge in high water, Captain Womp?” And he said, “Well, son, you hold on the right hand pier til you get a chill, and then you wait another minute. And then you hold on it for a while longer till you get a fever. And then you hold on that for another minute. And when the mate goes running out of the pilothouse screaming that you’re a lunatic, you wait another 30 seconds and then you might consider pulling off the right hand pier.” So all those bridges got their own little idiosyncrasies to them. And sometimes they get sometimes they get tapped.

Dean Klinkenberg 48:54

Did you ever tap any?

Lee Hendrix 48:56

I wouldn’t tell you about that. No, I did. That Clinton bridge up in Clinton, Iowa, I hit it with 15 barges one night and luckily didn’t do a whole lot of damage to the bridge. Broke some wires on the barges didn’t didn’t sink any of the barges. What other ones have I tapped. There’s a couple of those old railroad bridges up on the upper that you used to land in a really you make a controlled landing in it and try to kill your headway and then you could back back out and go around through like the old Hannibal Bridge, in high water used to pretty much count on land and on the sheer fence on that. Um, Pearl Bridge on the Illinois River landed in a few times. But that experience on the Clinton Bridge is probably the worst. I’ve come close, I thought I was going to do it. God was with me.

Dean Klinkenberg 50:12

I imagine if you’re a pilot long enough, those kinds of scrapes are inevitable at some point, you just kind of hope to minimize the damage from it.

Lee Hendrix 50:21

Oh, yeah, yeah, I mean, you know, anybody who’s been out on the river, they haven’t run aground or landed in a bridge or something, they either haven’t done anything or they’re lying. You know, it just happens. Happens to everybody.

Dean Klinkenberg 50:37

Right. So I imagine those of us who have the luxury of watching the boats from the shore, maybe we tend to glamorize a little bit the life of working and living on those boats. But you paint a portrait of kind of these lonely nights and feeling isolated a lot of the time. What is it about working on the river that you think makes it so difficult for folks for especially difficult to maintain relationships?

Lee Hendrix 51:09

Well, I always say it’s, it’s a nexus. it’s a nexus of danger, fatigue, and loneliness. So you’re up there at three o’clock in the morning, taking the boat down the river, a lot of times, you got nobody to talk to. So you become your own psychiatrists, while you’re up there, talking to yourself and thinking about all the mistakes you’ve made in life. And sometimes just think about the good things that you’ve done. And it’s easy to get distracted. A friend of mine told me that piloting is like, long stanzas of boredom punctuated by brief crescendos of utter chaos, that seemed like they can come out of the bushes at you. So you got to really keep your mind on what you’re doing. And sometimes it’s, it’s kind of hard. Because a human being, they can’t keep their mind isolated. Most human beings can’t keep their mind isolated on one thing that are that long of a period of time. So you’ve got the fact that you’re lonely, you’ve got the fact that you’re tired, because remember, pilots not going to get, or towboat pilots, not going to get more than four hours of sleep at a time, because of the shifts that you have to work. Six hours on, six hours off. So if you were very disciplined about going to sleep, right away, after you got off, watch, if you could do that, you might get four and a half hours of sleep. And you do that seven days a week, for a month at a time. So fatigue is a very big problem that you have to deal with. You have to be like I said, it’s exceedingly disciplined about your life. I mean, you could think of a priests as us. Pilots got to be just as disciplined as a priest or a fireman or, or anyone because you can’t, you can’t mess around after you get off watch. you got to at least go to try to get a few hours of sleep. And then there’s always that danger lurking out there. You got 10s to 1000s of tonnes of cargo up from in front of you. I just I can’t do it that like I used to do it. I’m I’m just not I’m half the man I used to be. It’s just human, you know, it’s just a lot of responsibility and very stressful on your body and on your mind. Does that kind of answer your question?

Dean Klinkenberg 53:45

Yeah. So what tricks did you learn for yourself that sort of help get you through all that?

Lee Hendrix 53:51

Never drink coffee. Now a lot of people do but I never drank any caffeine really because if you start on… I guess you could your body could become accustomed to that after a while but I always, toward the end, I very religiously stayed away from caffeine because that would keep me up and deprive me of sleep that I so greatly needed. Don’t eat a big meal and try to go to sleep. Try if you can to go out on the toe or even on the boat and make a couple of laps around you know to get your body moving. You know just basically be diligent about trying to get your rest. You got, you got to get it because you got to try to be on the ball as much as you can.

Dean Klinkenberg 54:47

And then I guess in place of caffeine you would just have your choice of music in the pilothouse to keep you going, like a little Metallica maybe or…

Lee Hendrix 54:57

Metallica. Yeah or Stone Temple Pilots or Cody Jinks or The Temptations. I don’t know I listened to I listened to it all. Depending on what mood I’m in. Usually, yeah, now that’s the one nice thing about today, most of the boats do have a Sirius Radio. I’ve worked on some boats where they have Sirius Radio actually, in my, in my cabin. So they realized that it’s important for a pilot to have something to at least keep them awake at night and used to be well, when I was a deckhand, I wanted to go up there and watch the pilot work because at some point in time I wanted to do that. And when I became a pilot, because those guys some of the deckhands knew that I would help train them, they would come up and we would talk and hopefully not talk so much that I was not paying attention to what I was doing. But keep my mind occupied. But now these guys today, they do they want they say they want to be become steersman, but you never see them all night. You’re up there sometimes six hours you don’t see as a solitary person. Like while you’re up there driving the boat, steering the boat.

Dean Klinkenberg 56:19

Well, I yeah, those sound like extraordinarily difficult circumstances to work in. So and you said like the length of your time on the boat has changed some now. So it’s multiples of a week, typically, rather than like, a month or 43 days or whatever you did your first time out. Maybe that’s one way to try. They’ve tried to manage a little bit better as having people off the boat or rotating off a little more quickly.

Lee Hendrix 56:45

Well, there’s still some masochists who like to stay out there longer than that, make make more money, you know. Oh, goodness, I’ve worked with guys who would stay out there five or six months at a time. I know, it’s hard to believe that people would actually abuse themselves that way, but, but they would. I guess they didn’t have any kind of a home to go back to. But yeah, normally I would say that the standard rotation these days is 28 days on and 28 days off. Now there’s some that do that a little bit differently than that, but but if there’s if there is a norm that would be it.

Dean Klinkenberg 57:25

So you kind of wrote early on in the book, like the old river river lore that if you wore out a pair of boots on the river, the river basically has you for life or you’re hooked on the river for life. What do you think it is about the river that keeps us coming back? You know, what is it that kept you going back to the river?

Lee Hendrix 57:47

Well, I mean, the the fact that it is kind of kind of difficult, you feel like you’re doing something that not everybody would maybe be able to do. So you kind of feel like it’s unique. And then there are a lot of very enchanting moments out there. Peaceful moments where you’re steering the boat or like say for instance, you’re on the Ohio River between I don’t know Smithland and JT Myers Lock, but on the Ohio you got a long pool, that deep water, there’s no other boats around the moon’s full. You got Sirius radio to listen to, it’s really magical that you’re you know, you can just kind of sit there and relax and just steer the boat up and down the river in a full moon night like that. It’s you feel like you’re really lucky that a lot of the people are really missing out on those people are back there at home sleeping are really missing out on something. They don’t realize how deprived they are. And the money is good now too. There’s people working, I mean, I have been I’ve got a degree or two, but I could be doing my job. It’d be doing them with a sixth grade education. And I’m not trying to sound arrogant. That way. I hope it doesn’t come across like that. But you don’t need a lot of formal education to do that job and you can make more money out there than a lot of people who do have masters degrees so the money is good. The flip side of being on a boat for 28 days is your off 28 days. So you can go home and you can plan a trip. So it’s a there’s there’s trade offs there. And once you it’s like any other profession, I guess once you reach a certain comfort level and a certain economic level. You don’t want to leave it because where am I going to go now or I can make make that kind of money.

Dean Klinkenberg 59:58

Right. So how did all your years working on the river, impact the way you see the river?

Lee Hendrix 1:00:08

Oh, you know, you’d become familiar with it. This you’d be just like you. I mean, you live you live near Tower Grove Park, right? I do. So you go down Kingshighway and over to what is what is that your Magnolia and go to Magnolia over to Grand and you just you just know that route, you know, something doesn’t look right to you know it and well, yeah, you’d obviously become more familiar with it. Now, having said that, sometimes, when you do go over in a river that you haven’t been for a while, then you’ve got to go back through the files. It’s still in your memory, you have to go back through those files. And it’s kind of a sentimental journey sometimes to go like the Illinois River. I made a trip up there a couple years ago and I was thinking, oh, man, I ran aground right over there. You know, that’s where old Buddy and me went to town and brought back two cases of Pabst Blue Ribbon and that that kind of thing. Or when I got to make a trip, I got to make a trip up the Arkansas River and I was I was, well Austin’s a red eyed terrapin up there. But, you know, I managed to pull through so that really kept me on my on my toes going to go into a different river. So there’s things that will pop up that will become challenging for you.

Dean Klinkenberg 1:01:43

Absolutely, yes. Oh, and we have a fair number of paddlers who listen to this podcast, I’m sure they would love to hear from somebody who’s worked in the pilot house of a tow or from one of the passenger ships. If you had any tips for how to share the river with the paddlers from the paddlers. You know, from your perspective, what can they do to help share the river and do so responsibly?

Lee Hendrix 1:02:09

Well, I’ve been a paddler myself, you know, my friend Tom Bell, I used to take people on the river and we had some 26 foot fiberglass canoes, we took people out so I can share it with paddlers on the river. I certainly enjoy sharing the river with them. Maybe not everybody piloting a boat out there would feel the same way about that. But even if they don’t like you being out there, they still don’t want to run over you. So they’re there, they’re there to try to keep keep you safe. You have to realize, like, say, for instance, you’re coming down through St. Louis harbor, and you’ve got a pretty big tow, 15 barges. And if you’re in a canoe out there or kayak, you have to realize that it takes that tow boat pilot a long time to stop that tow, and even to maneuver out around you. So it’s probably in your best interest to try to stay out of their way. The best way to do that is well, and you might not realize this if you’re a paddler, but they’ve got a certain span on those bridges, they’ve got to run and they’ve got to shape up properly for those spans of those bridges, particularly like Eads Bridge. Or they can take the whole top of their pilot house off. So it’s a good idea to know a little bit about like the lay of the lay of the river, the lay of the land, knowing where that person is likely to go. If you can get hold of a chart, see where the sailing line is called the sailing line. And that’ll show you where the majority of the time the bigger boats will go. Now, there’s some nuances to that though, too. You come down into a bend like Four Charters Bend which is done around St. Genevieve. When they come around that, they’re taking that whole bend because they got to stick one end out on the green buoys. If they don’t like bust up on the revetment on the Illinois shore. So if you’re going to be in that area with them, you probably need to be completely out of the channel. And often, you know, with shallow draft vessel like a canoe or kayak, you could do that. But you know, sometimes maybe you you couldn’t do that either. So you’re you’re playing a dangerous game out there, really and that’s not say you shouldn’t do it. But you should try to find out as much as you possibly can about what those towboats how they have to shape up for a bridge or a lock or, or even just going going down the river. Now, they will almost invariably pass along to each other when we see kayaks or canoes out on the river. So we know where they’re going to be. And I don’t know if anybody wants to invest in this, but a radio is not a bad thing to have.

Dean Klinkenberg 1:05:37

I was going to ask about that. Like, if you prefer it, or didn’t mind if somebody’s in a canoe or kayak, just use their marine radio to say, “Hey, I’m out here in such and such location.” Like, what would you like them to tell you, let’s say if they contacted you over the radio?

Lee Hendrix 1:05:54

Well, let me know where they are. Like you said, I can figure out about how fast they’re going. That’s, that’s not hard to do, they’re not going to be going real fast. Obviously want to know which way which way they’re going. Mainly, it’s up to me to let them know how much room I need, and where’s the safest place for them to go. Because they don’t realize how much that tow can slide from one side of the river to the other. So even though it looks like they’re going to be in one place, if you wait a few minutes, they might be completely over on to the other side of the river. So yeah, and don’t be afraid of talking to the guys. I mean, most of them would like to communicate with you so that they know, to tell you where the safest place for you for you to go is. Now you might not understand the language, right. So it’d be a little bit of a learning curve there. But different and the river has its own parlance. I remember when we were doing the Mississippi River Youth Expedition back in the 1980s, they had me on there with the, and they had me talk to the to the towboats because I understood the language so I could figure out how we were going to go about keeping from getting getting killed out there on the river.

Dean Klinkenberg 1:07:37

Well, Lee, we’re probably running a little close to the end here. So before we finish, you’ve got a book coming out. Why don’t you tell us a little bit about your book?

Lee Hendrix 1:07:47

My book is called “Peep Light”. So my original title was going to be “Where the Peep Light Leads”, because it was a metaphor for life. The peep light is out on the head of the tow, it’s a little blue light. At night, you use it to judge the swing of the tow. So the metaphor was – I’m following my peep light physically and spiritually up and down the river. And I proposed that to the University Press in Mississippi. And they said, well, that’s kind of cool, but nobody isn’t going to know what the hell a peep light is, so we’re going to expand the title a little bit. We’ll call it “Peep Light: Stories of a Mississippi River Boat Captain.” And it actually, I, they told me it was going to be published in the middle of February, but some of my friends in St. Louis have already got their copies. So you can go to University Press of Mississippi. It’s got a pretty cover with an American flag and a boat in the Mississippi on the front. And or you can go to Amazon, or Ingram Books or Barnes and Noble any of those places.

Dean Klinkenberg 1:09:01

So it’s a it’s a collection of essays about your experiences on the river, just a bunch of stories about the things that happened to you during your career working on the river.

Lee Hendrix 1:09:12

Longest story is probably about 23 pages, there’s a couple of short ones that are maybe about a page.

Dean Klinkenberg 1:09:19

Well, if people are interested in following your work, or what you up to, do you have a website, or do you have any social media forums where you like to post things? How can people follow what you’re doing?

Lee Hendrix 1:09:32

So you can go to University Press of Mississippi homepage and just look for my book and they’ll they’ll tell you about it. Really soon. But the only thing I got going on other than that is walking the dog.

Dean Klinkenberg 1:09:46

Well, thank you so much for taking the time to talk with me today. I really appreciate it. Like I said the book is really enjoyable. There’s some really great stories in there. You tell them well, it’s a fairly fast read. I thought I was able you know I was able to read it in maybe two or three days and just just really enjoyed it. So thank you for sharing those experiences for the book and through this podcast.

Lee Hendrix 1:10:09

Thank you Dean. Appreciate it. Smooth sailing.

Dean Klinkenberg 1:10:22

And now it’s time for them Mississippi Minute. Lee and I had a little conversation during the interview about his perspective for how paddlers can safely operate around barges on the Mississippi and any advice he had for paddlers who are approaching or near barges. I just want to expand on his advice a little bit. First of all, I want to emphasize that it’s perfectly fine to paddle on the Mississippi. You need mid range to expert level skills, and you really need to be aware of what’s going on around you. You need to be watching for commercial and recreational traffic when you’re out there. It’s your responsibility to stay out of the way of barges and it’s a smart thing to also give recreational boaters a wide berth. If you’ve been paddling in the main channel and you see a barge coming then get out of the channel and move out of the way until the barge passes and be prepared for a few waves in the barges wake. But just don’t get too close to shore because the waves ricochet off the shore and you may quickly destabilize your boat if you’re getting hit from two different directions with waves. The waves really aren’t too bad if you if you’ve dealt with waves before and water you know how to deal with this. Barges aren’t so bad. Sometimes recreational boaters kick up more of a wake to be honest, especially if they don’t slow down when they’re passing paddlers so I tend to be more concerned about the recreational boaters but I’m curious what your experience has been. If you’re gonna be out on the paddling for a little while, you can use an app like FindShip that will show you where the commercial boats are. Very handy app with electronic readings and names for the ships that are anywhere nearby. If you’re just gonna be out for some day trips, though, it’s just fine to pay attention to what’s going on around you, you don’t really need an app like that. Don’t forget to regularly turn around and look behind you. Down river barges are surprisingly quiet and fast and they can sneak up on you before you know it. So always make sure to turn your head periodically to see what’s coming up behind you. Now if you want to communicate with the pilots of a commercial boat to let them know that you’re in the area you’ll need a marine radio and when you contact them, don’t get chatty, you know they’re busy people. Just tell them where you are and where you’re going. And you really just want to assure them that you’re going to stay out of their way. The Mississippi River Water Trail has a website with some safety tips for paddlers on the Mississippi. I will post a link to that in the show notes. And if you have any questions, just feel free to contact me at MississippiValleyTraveler.com/contact. Thanks for listening. If you enjoyed this episode, subscribe to the series on your favorite podcast app so you don’t miss out on future episodes. I offer the podcast for free but when you support the show with a few bucks through Patreon you help keep the program going. Just go to patreon.com/DeanKlinkenberg. If you want to know more about the Mississippi River, check out my books. I write the Mississippi Valley Traveler guide books for people who want to get to know the Mississippi better. I also write the Frank Dodge mystery series set at certain places along the river. Find them wherever books are sold. The Mississippi Valley Traveler Podcast is written and produced by me, Dean Klinkenberg. Original Music by Noah Fence. See you next time.