Did a 70-foot-long river behemoth really lurk in the river’s channel in the 1870s? Are there monsters in the river’s depths that have eluded us so far? In this episode, we delve deep into the Mississippi’s murky waters and mystical swamps to uncover stories about the terrifying creatures that we have imagined prowl the river.

We also take a deep dive into a much smaller—and deadlier—monster along the river. The mosquito. We dig into stories about the swarms of mosquitoes that plagued early settlers, bugs that brought with them deadly diseases including malaria and yellow fever. We relate the stories of the devastating yellow fever epidemics that swept through cities New Orleans and Memphis, leaving a trail of death and despair.

Are you brave enough to venture into the mystical, monster-filled world of the Mississippi? Don’t forget your lucky charm—you’re going to need it!

NOTE: This episode includes graphic descriptions of the effects of yellow fever on the human body.

Show Notes

Below are photos of three varieties of orchids native to Minnesota: the Showy Lady’s Slipper, the Yellow Lady’s Slipper, and the Dragon’s Mouth.

Support the Show

If you are enjoying the podcast, please consider showing your support by making a one-time contribution or by supporting as a regular contributor through Patreon. Every dollar you contribute makes it possible for me to continue sharing stories about America’s Greatest River.

Don’t want to deal with Patreon? No worries. You can show some love by buying me a coffee (which I drink a lot of!). Just click on the link below.

Transcript

43. Monsters Real and Imagined

Sun, Jun 16, 2024 5:41PM • 45:51

SUMMARY KEYWORDS

yellow fever, mosquitoes, city, mississippi, malaria, memphis, river, monster, disease, day, epidemic, people, creatures, spread, residents, wrote, street, work, north america, piled

SPEAKERS

Dean Klinkenberg

Dean Klinkenberg 00:00

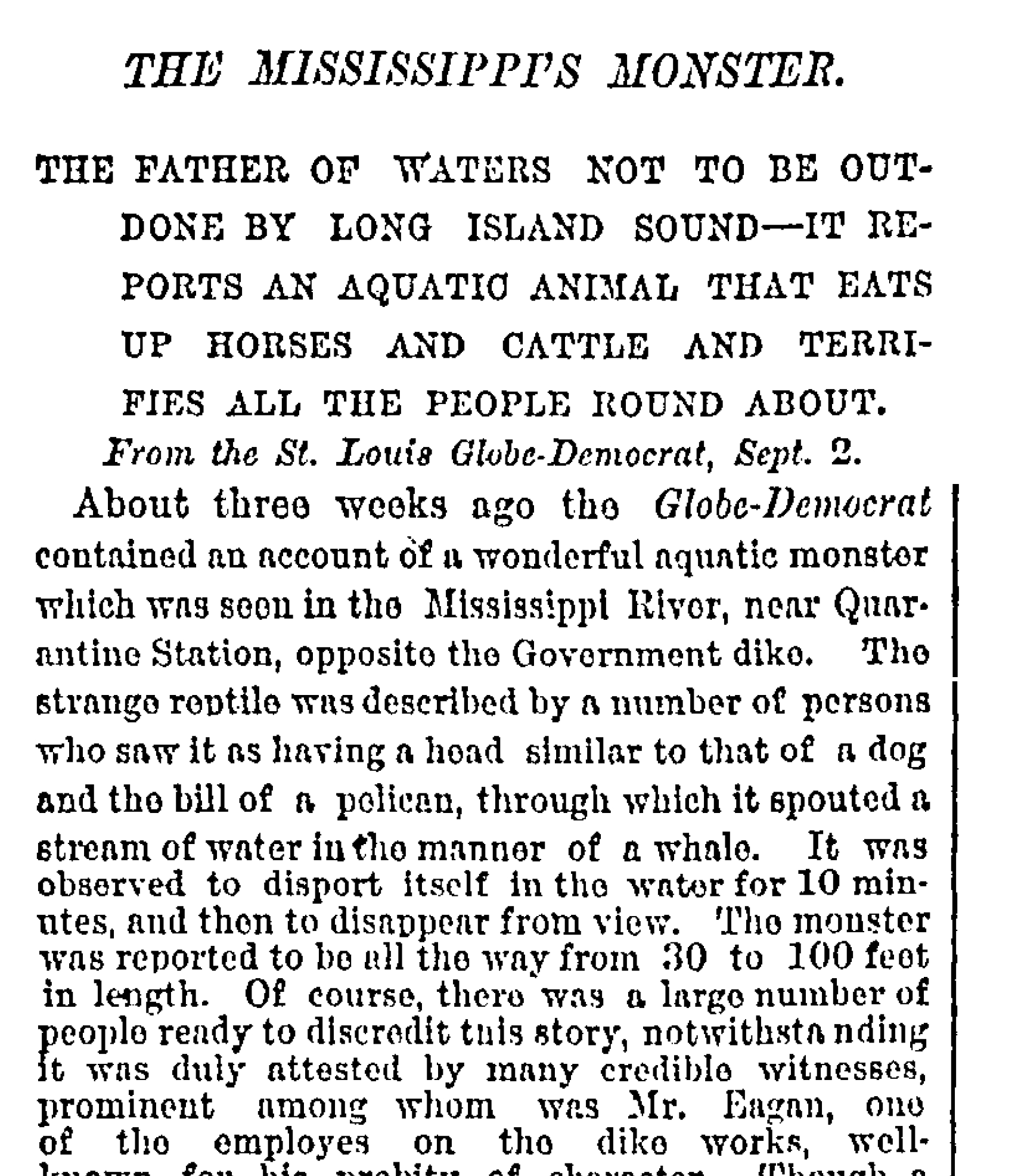

Folks along the Mississippi may fear floods, but at least the high water eventually goes away, If only that were true for the creatures that lurk in the turbid waters, the mystical swamps and the dark forests. What could be hiding in those places? Welcome to the Mississippi Valley Traveler Podcast. I’m Dean Klinkenberg and I’ve been exploring the deep history and rich culture of the people and places along America’s greatest river, the Mississippi, since 2007. Join me as I go deep into the characters and places along the river, and occasionally wander into other stories from the Midwest and other rivers. Read the episode show notes and get more information on the Mississippi at MississippiValleyTraveler.com. Let’s get going. Welcome to Episode 43 of the Mississippi Valley Traveler Podcast. I know it’s not Halloween, but for some reason, I’ve been thinking about monsters lately. So don’t ask me why. It’s not worth going there. So in this episode, I want to tell you a little bit about some old monster stories, and then go deep into the world of a monster we’re all far more familiar with, mosquitoes. Some of this is adapted from my book “Mississippi River Mayhem”. You can find that wherever books are sold. If you want to read the whole book. A couple of quick announcements. I have two events coming up at Left Bank Books in St Louis. If you’re in the area, come on by on Tuesday, June 18, I will be there for Boyce Upholt’s book release party. June 18, 6pm at the Schlafly Public Library in the Central West End, 6pm. Boyce will be talking about his new book, and I’ll be facilitating a Q and A session with him. The week after that, on June 25 I will be talking about my own book, “The Wild Mississippi”, at Left Bank Books in the Central West End. That is also at six o’clock. So if you’re in the St Louis area, I’d love to see you at one or both of those events. As usual, you’ll find the show notes at MississippiValleyTraveler.com/podcast. You can also go there to leave a comment on an episode, if you so wish. And I would love to hear from you as always. Thanks to those of you who show me some love through Patreon. Your support makes me feel good and keeps this podcast going. You can join the community for as little as $1 a month, just $1 a month, and it gets you early access to the podcasts. If that’s not your thing, if you don’t really want to become a subscriber through Patreon, you can buy me a coffee. I have a pretty good caffeine habit, so every penny that goes to help support that, I appreciate as well. For information on how to join Patreon or buy me a coffee, go to MississippiValleyTraveler.com/podcast. And now let’s get on with the episode. Folks along the Mississippi may fear floods, but at least the high water eventually goes away. If only that were true for the creatures that lurk in the turbid waters, the mystical swamps, and the dark forests. What could be hiding in those places? Demons! Well, sure, there might be a gator or a cottonmouth, but it’s the demons you have to watch out for, especially in those swamps, and especially at night, when the moon rises over the Mississippi. Better bring along a lucky charm for protection. Stories of dangerous river creatures have persisted for centuries. In 1673 the Ojibwe warned Father Jacques Marquette and Louis Joliet that the river was full of giant monsters that could devour men and their canoes in a single bite. The only scary creature that Marquette and Joliet encountered firsthand, though, was a large catfish that struck their canoe. A collision that certainly frightened the heck out of everyone, even if the fish didn’t consume the explorers for dinner or take a bite out of their canoe. Marquette and Joliet may not have encountered any actual monsters, but they were the only Europeans to see a cliff painting of a mythical beast that we now call the Piasa bird that was painted on a bluff face near present day, Alton, Illinois. The images actually depicted two monsters, as Marquette described it, “While skirting some rocks which, by their height and length, inspired awe, we saw upon one of them, two painted monsters which at first made us afraid and upon which the boldest savages dare not long rest their eyes. They are as large as a calf. They have horns on their heads like those of a deer, a horrible look, red eyes, a beard like a tiger’s, a face somewhat like a man’s, a body covered with scales and so long a tail that it winds all around the body, passing above the head and going back between the legs, ending in a fish’s tail. Green, red and black are the three colors composing the picture. Moreover, these two monsters are so well painted that we cannot believe that any savage is their author. For good painters in France would find it difficult to reach that place conveniently to paint them.” By the time the next Europeans came to the area the paintings were gone. Contemporary interpretations of the images now decorate the bluffs near the original location. And check the show notes for a photo of the Piasa bird today. Two centuries after the Joliet Marquette expedition, newspapers reported that some folks had spotted a monster nearly as big as an elephant rising out of Lake Pepin. Lake Pepin is a natural widening in the Mississippi’s channel for 22 miles. The river spreads as wide as two and a half feet (edit: miles) and runs about 20 to 30 feet deep. Stories of monsters in Lake Pepin predate the arrival of Europeans. The Dakota who lived in the area preferred travel on the lake in sturdy dugout canoes. They knew of creatures in the lake that had a habit of punching holes in birch bark canoes. While no one has ever captured proof of a big monster, locals have embraced the story, and you can buy a t-shirt today with the image of this creature, which we now call “Pepie”, and it has a rather cuddly appearance, not unlike Dino from the Flintstones. A few years later, another monster in the Mississippi made national news as newspapers across the US reported sightings of it. In 1877 eyewitnesses reported spotting this monster at St Louis near Quarantine Island. At first, the stories were dismissed as pure fancy, but then three men near St. Genevieve reported finding a big monster sunning itself on a beach near their farms. The snake like beast, spanned 70 feet long. Its body covered with shiny brown scales, with the head of a dog or maybe a sea lion, but with a five foot long beak, possibly made of ivory, a rough mane around the neck, six legs and a pair of fins. It was apparently equipped for life on land or in the water. The men fired shotgun blasts at the creature, which groaned then slipped into the river, shooting water 10 feet high as it slipped under the surface. After the story of their encounter circulated, another man in the area claimed he watched as a horse swimming across the river suddenly went under and did not resurface. Another farmer said one of his horses, one that loved to drink from the river, had recently disappeared. And yet, another farmer said he had recently found the head and horns of a cow that had washed ashore. He was certain he had seen that same cow drinking near the river just an hour earlier. A few days later, folks crossing the river on a ferry near New Madrid spotted the monster again. The boat shook suddenly, dumping one man into the river. He pulled himself back in safely, but another sudden movement shot the boat straight up in the air as the boat landed back safely on the water, the folks on the ferry saw the monsters swimming away from them, shooting water 10 feet high and leaving whirlpools in its wake. The New York Times article reassured readers that the eyewitnesses were “People well known here for their veracity.” No doubt, reassured by the trustworthiness of these eyewitnesses, PT Barnum offered $100,000 to anyone who captured the monster and brought it to him. A few weeks later, the monster made another appearance, this time on the Lower Mississippi near Island 95. Once again, it nearly submerged a boat and created whirlpools as it swam away. Folks at Natchez were reportedly scared off the river for a few days after that, A few weeks later, fisherman John Edwards announced he had captured the monster near Memphis and offered public tours of his catch. It seems folks were unimpressed, though, as few showed up to get a look. Especially those who peeked at the calendar and wondered if it was merely a coincidence that his story ran for April 1st. Near New Boston, Illinois, John Maddox had a fine day interrupted 1936. After swimming a few laps back and forth across the river, his shoreline rest was abruptly interrupted when a 120 foot snake like critter popped out of the river and roared, “Like a dozen locomotives blowing off steam.” Its head rose some 20 feet above the water. Its scales clanked like chain mail. Blue smoke flowed from its nostrils and its eyes burned red. Maddox passed out in fright, and when he came to, maybe sobered up, the snake was gone. Our fears about monsters in the river aren’t entirely unfounded. American eels slime their way from the Sargasso Sea up and down the Mississippi. Leeches inhabit the waters of northern Minnesota. In 1937 commercial fishermen Dudge Collins and Herbert Cope caught an 84 pound bull shark in the Mississippi River near Alton, Illinois. Bull sharks can survive quite a while in fresh water it turns out. Paddlefish, blue catfish and the alligator snapping turtle, can easily weigh 100 pounds or more. Just ask Davy Crockett, he wrote about, “A monstracious, great catfish better known by the name of a Mississippi lawyer”, that he fought an epic battle with on the river. Lawyers can be scary enough, of course, but this one was a feisty 12 footer, probably a blue catfish with sharp scales, and a seemed intent on making lunch out of Crockett. Spoiler alert, Crockett won. Other fish in the Mississippi can be even bigger and scarier. In 2011, Kenny Williams of Vicksburg, Mississippi caught an eight and a half foot, 327 pound alligator gar in the Mississippi. A primordial creature that looks more dangerous than it really is. Something that’s easy to forget when it’s swimming right at you. Creatures don’t have to be big to be scary, just hungry and abundant. Boll weevils, just six millimeters long apiece, ate their way up the Mississippi Valley in the 1920s, destroying 1000s of acres of cotton plants. And the bowfin, also known as a dogfish, or sometimes as John Grindle is a fish with old roots. It swam with the dinosaurs. Well, okay, I don’t know that it was literally in the water at the same time, but bowfin and dinosaurs shared the planet for a while. Generally weighing around 10 pounds, the bowfin is an aggressive predator, willing to attack just about anything, no matter how much bigger it is. One of its more adaptive features is it has an air bladder that can function like a lung. You could pluck a bowfin out of the water and drop it on land, and it will survive for nearly a full day. If the sight of a fish with lots of sharp teeth flopping around on the ground for hours doesn’t scare you away from the Mississippi, then I suspect not much will. During a hike a few years ago, I made an impulsive stop to check out an overlook at Savannah Portage State Park in northern Minnesota. Overlooks are rare in this glacier flattened landscape, so I was pretty excited to get to it and see what the view was like. Within a few steps after hitting the trail, I was engulfed in a cloud of mosquitoes so thick that I swear I could have killed hundreds just by snapping my fingers. There are parts of the world like that one, where mosquitoes are so abundant that I’m surprised a mosquito eating equivalent of a whale shark hasn’t evolved. A creature that could glide through the air with its long, thin mouth wide open, vacuuming up the little suckers for food. We love complaining about mosquitoes. I sure do. When I lived in Minnesota, we joked that the mosquito was the state bird. I imagine in Florida or Louisiana, maybe there are similar jokes. Old timers, stoic men and women with Scandinavian sensibilities, insisted they had seen mosquitoes large enough to carry off a cat or a small child. It’s all part of a long tradition. French traders, including Henri de Tonti, founded Arkansas Post in 1686, to trade with neighboring Quapaw Osage and Caddo people. They built near the confluence of the Arkansas and Mississippi Rivers, a swampy area that proved challenging for Europeans, especially because of the abundant mosquito population. In 1727, the post priest Father Paul de Poisson, wrote, “The Egyptian plague was not more cruel. This little creature, the mosquito, has caused more swearing since the French came to Mississippi than had been done before that time and all the rest of the world.” In 1826, Reverend Timothy Flint wrote, “The mosquitoes swarm above the water in countless millions. I traveled 40 miles along this river swamp. I was enveloped for the whole distance with a cloud of mosquitoes. Nothing interrupted the deathlike silence, but the hum of mosquitoes.” These thick clouds of mosquitoes inspired some creative coping techniques. Flint wrote, “The inhabitants while jesting upon the subject, used to urge this incessant torment as an excuse for deep drinking a sufficient quantity of wine or spirits to produce a happy reverie or a dozing insensibility. Had a cant but very significant name, ‘a mosquito dose’.” I could probably record an entire episode’s worth of hate filled quotes about mosquitoes, but you get the idea. Let’s move on. Mosquitoes have been buzzing around this planet for some 50 million years. There are now 1000s of species of mosquitoes, and while they all share an attraction to carbon dioxide and that universally irritating buzz, they are a remarkably diverse group of creatures. Some species love the night life, while others prefer the bright a day. Some can’t live without blood, while others are essentially vegan. While most species are no more annoying than screaming children in a coffee shop, a very few are very deadly. These outliers may be responsible for more human deaths than any other creature except perhaps humans ourselves. Mosquitoes in the genus Anopheles are among the most notorious. Females in 30 to 40 of the 430 Anopheles species carry the plasmodium parasites that cause malaria, a disease that some scientists estimate has been responsible for half of all human deaths since the Stone Age. Malaria was unknown in North America before European colonization. The first cases probably came to the continent with Hernando de Soto in the 16th century. Malaria and other diseases carried by the conquistadors spread throughout the southeast, killing 1000s more people than the conquistadors killed directly, wiping out whole communities in the ensuing years. Malaria eventually ran its course and disappeared from North America for a while, only to reappear when the next round of Europeans returned. In 2013 nearly 200 million people around the world contracted malaria, with nearly half a million dying from it, most of them children. People whose ancestors lived in malaria prone areas in North America that was primarily enslaved Africans, inherited a genetic adaptation, the sickle cell gene, that developed over millennia and hundreds of generations to reduce the mortality of malaria. Individuals who have a single copy of the sickle cell gene are 90% less likely to die from malaria than those without the gene. Unfortunately inheriting two copies of the sickle cell gene nearly guarantees the development of sickle cell anemia, a disease that few survived beyond childhood. The Anopheles mosquito thrives in agricultural areas. As forests were cleared for farming in the Mississippi Delta, the population of Anopheles mosquitoes spread with cotton. All those acres of cotton fields provided fertile habitat for Anopheles mosquitoes, the 1000s of puddles and wheel ruts and furrows which the mosquitoes used for breeding. With a favorable habitat in a growing human population, malaria spread quickly. Wealthy folks typically traveled away from malaria prone regions in summer. So the disease took an especially heavy toll on the poor who didn’t have the luxury of packing their steamer cases and heading north. In North America, residents of Arkansas suffered more than most. Cases were widespread well into the 20th century. Surveys in the 1930s found the parasite present in nearly a quarter of the population in some communities. The disease had been a fact of life for so long that many people self medicated with quinine and only went to a doctor if the quinine didn’t work. Infection rates were eventually reduced with an ambitious public health program, which culminated with the National Malaria Eradication Program in 1947. The primary tool was DDT, which was blasted around in areas where malaria was endemic. Other measures included draining swamps, introducing gambusia minnows to bodies of water where mosquitoes bred. Those fish feast on mosquito larvae, and putting screens on windows and doors. All those efforts worked. In 1945 Arkansas reported over 2000 cases of malaria, but just six years later, there were none. Of course, all that DDT had some unforeseen negative consequences. Hey, Dean klinkenberg here, interrupting myself, just wanted to remind you that if you’d like to know more about the Mississippi River, check out my books. I write the Mississippi Valley Traveler guide books for people who want to get to know the Mississippi better. I also write the Frank Dodge mystery series that is set in places along the Mississippi. My newest book, “The Wild Mississippi” goes deep into the world of Old Man River. Learn about the varied and complex ecosystem supported by the Mississippi, the plant and animal life that depends on them. And where you can go to experience it all. Find any of these wherever books are sold. Malaria wasn’t the only mosquito borne disease that residents of the Mississippi Valley feared. While malaria became a fact of life along the Lower Mississippi, yellow fever terrorized whole communities with sporadic outbreaks that sent city residents fleeing for the country. Like malaria, yellow fever wasn’t native to North America. The yellow fever virus probably traveled to the Americas on slave ships from Africa. Female mosquitoes in the species Aedes aegypti, pick up the virus from infected people and spread it around. In North America, the disease proliferated during the warmer months of the year, typically July to October, although it didn’t disappear completely until the first frost that killed the mosquitoes. There was a common belief at the time that yellow fever was a manageable disease if you took care of yourself, especially if you didn’t drink alcohol, ate properly and lived a moral life. Some newspaper accounts even extolled the benefits of yellow fever infection as, “invigorating”, claiming that, “It reconstitutes and reorganizes the system and makes a man almost proof thereafter against the disease.” People who survived yellow fever did indeed acquire lifetime immunity, although exactly what that meant wasn’t well understood at the time. There was a belief, for example, that blacks had natural immunity to yellow fever. Many whites saw this as another justification for slavery. Some Christians believed that God had given blacks immunity to yellow fever so they could work the cotton fields instead of whites, who were believed to be far more likely to die if infected. The idea that blacks had a natural immunity to yellow fever just wasn’t true, though, and some people at the time obviously knew that. White enslavers, for example, were willing to pay more for blacks who had survived yellow fever. Immunity was only acquired when a person was exposed to yellow fever and survived, and that immunity, or what people at the time called ‘becoming acclimated’, carried considerable currency, especially in New Orleans. One newspaper noted that the acclimated resident “Walks along the street with a tremendously bold swagger.” It was hard to get a decent job or marriage partner if you hadn’t yet been exposed to yellow fever. For that reason, some people chose to stick around so they too could become acclimated. It was a risky decision, about 15% of those infected got very sick, usually after the third day. If you were in that unlucky group, your odds of surviving were as good as picking heads on the coin flip. Death from yellow fever was an unpleasant way to exit the earthly plane, and the time from the first onset of symptoms to severe illness could be shockingly brief. Theodore Clapp recalled, “Often I have met and shook hands with some blooming, handsome young man today, and in a few hours afterwards, I have been called to see him in the black vomit with profuse hemorrhages from his mouth, nose, ears, eyes and even the toes. The eyes prominent glistening yellow and staring, the face discolored with orange color and dusky red.” After the initial bout of fever and general discomfort, a couple of days of muted recovery fooled many into believing that they had survived the worst. When symptoms returned, though they were much more severe, one of the most terrifying sites was when victims in late stages of the illness vomited black, colored blobs, partially digested blood, which is why the Spanish name for disease translates as the black vomit. As the disease ran its course, the virus damaged the liver, which caused jaundice that turned its victim’s skin the color that gave the disease its English name. Yellow fever, in its final insult, molded a tormented expression on the face of the dead. Theodore Clapp in 1858 wrote, “The physiognomy of the yellow fever corpse is usually sad, sullen and perturbed. The countenance dark, mottled, livid, swollen and stained with blood and black vomit. The veins of the face and whole body become distended and look as if they were going to burst, and though the heart has ceased to beat, the circulation of the blood sometimes continues for hours, quite as active as in life.” Aedes aegypti mosquitoes thrived in North America’s urban environments, and daylight did not deter them. The earliest yellow fever outbreaks raged through the major cities of the Northeast, starting at the end of the 17th century. Philadelphia and New York routinely lost up to 10% of their residents during these sporadic epidemics over the next century. Yellow fever eventually faded away for reasons that aren’t entirely clear, but improved sanitation practices and regular use of quarantines probably helped. The northern climate also made it nearly impossible for the aedes mosquitoes to survive long. So an epidemic could only begin when both the mosquito and the disease arrived, usually via ships from the Caribbean. In the south, though Aedes mosquitoes were already abundant when ships from the Caribbean or South America arrived with passengers infected with the disease. Yellow fever found a welcoming home in the American South. No city suffered the effects of yellow fever more than New Orleans. From 1804 to 1860 New Orleanians endured 22 major outbreaks of yellow fever, one of the worst epidemics swept through the city in 1853, a year that had started with great optimism. The city’s economy was thriving thanks to record cotton yields and expanding railroads had funneled new commerce into the city. The first cases were identified in May, but it spread slowly through June, the time of year when upper class residents took their summer leave of the city anyway. June was also a great month to be a breeding mosquito. On June 28 the Daily Picayune reported that, “A barbarous horde of great, ugly, long billed, long legged, fly away creatures has invaded our streets and houses and taken possession of our domestic goods.” By early July, the outbreak had picked up steam and fear spread with the virus. By the end of the month, nearly 100 people were dying every day, “The morning train of funerals, as was this evening’s crowded the road to the cemeteries. It was an unbroken line of carriages and omnibuses for two miles and a half.” Charity Hospital filled beyond capacity, forcing staff to lay some patients on the floor. Some of the sick were treated with quinine. Others were treated with cupping or blood letting. Some physicians even advised the afflicted to drink their own urine or to eat spiders. There just wasn’t a lot of uniformity and treatment options. As the disease raged through the city, bodies piled up at burial grounds. One resident, “saw coffins piled up beside the gate and in the walks and laborers at work digging trenches in preparation for the ‘morrows dead. A fog which hung over the moss enveloped oaks, prevented the egress of the dense and putrid exhalations. The atmosphere was nauseating to breathe that I have never noticed in a sick room.” As the deaths accumulated, the stench of rotting corpses filled the air. Residents covered their noses with rags soaked in camphor or spices to mute the smell. Grave diggers were in short supply, so family members sometimes had to bury their own. Funeral parties often arrived at the same time, which resulted in so much conflict that police had to be stationed at cemeteries to keep the peace. The City eventually hired more people to dig graves. They were paid as much as $5 an hour and given free liquor and sped up the process by burying the dead in trenches instead of individual graves. As the death toll increased to 200 a day, City officials grew desperate. Some public health officials recommended purifying the air, so cannons were fired 50 times a day, but the only effect was that New Orleanians became more agitated. The City discontinued the cannon fire after a couple of days. City officials also set barrels of tar afire, which draped the city in a suffocating, oily fog. River traffic was down, but the City didn’t close the port. So ships continued to dock. Some of those ships brought in new groups of immigrants who moved into the city then contracted yellow fever. In some cases, the disease wiped out entire immigrant families. On August 20, nearly 300 people died. The epidemic had peaked. By the time it was over some 40% of the city’s residents had been infected, and upwards of 11,000 had died, most of them newly arrived immigrants. People who left the city as the epidemic raged in New Orleans carried yellow fever up the Mississippi River, contributing to major outbreaks in Baton Rouge, Natchez and Vicksburg. On October 13, the City’s health commission declared the epidemic over. People returned to the city and businesses opened back up. The rhythms of life returned normal, and the newly acclimated walked the streets with a swagger. 25 years later, a virulent yellow fever epidemic nearly wiped out Memphis. Founded in 1819 by a group of investors that included future President Andrew Jackson, Memphis built up in the homelands of Chickasaw Indians, and in the heart of the area where pre-European Mississippi cultures had thrived. After the Civil War, Memphis grew rapidly thanks in part to the migration of blacks from the rural south. That rapid population growth overwhelmed the city’s built environment. Poor sanitation practices, open sewers were common, gave Memphis a reputation as the most foul smelling city in the country, and contributed to the rapid spread of disease. There was no sanitation system for human and animal waste, so most of it flowed down streets and gutters and into a bayou in the middle of town that served as the city’s sewer. Garbage and animal carcasses piled up in city streets, pools of water collected around bridge piers and basements and on city streets, which provided fertile breeding grounds for the aedes mosquitoes that spread yellow fever. Memphis had its first brush with yellow fever in 1855. An outbreak that killed 150 people. Memphians lived through another minor yellow fever outbreak in 1867 although it wasn’t trivial for Mary Jones, that epidemic took the lives of her husband and all four of her young children. She moved away from Memphis after that, and later gained fame as an activist for working people. She was better known by her nickname “Mother Jones”. When yellow fever killed 2000 people in 1873, Memphians had to shed their belief that their more northerly location protected them from significant yellow fever outbreaks. Just five years later, any remaining doubts were shattered. In early August 1878, word reached Memphis that yellow fever was spreading in Grenada, Mississippi, a town just south of town. A few days later, Memphian Kate Bionda took ill and died from the disease. Bionda and her husband ran a food stand on the riverfront. City officials responded quickly. J M Keating wrote about this in his account of the epidemic, “Immediately, Health Officer Erskine took charge of the building and vicinity, the rooms, house and premises were thoroughly fumigated and disinfected with carbolic acid, copperus, etc. The sidewalk and street for half a square on Front Street and the same distance back on Adams were also disinfected. An obstruction or railing was placed across Adams Street at Center Alley, and the locality number 212 was fenced in around Front Street to the intersecting alley running east and west. Not only was the building in which Mrs Bionda died disinfected and isolated, but all adjacent buildings in the block were likewise disinfected, and policemen were stationed to prevent people from visiting that particular locality.” Those efforts weren’t nearly enough, though, cases spread across the city, and when the Board of Health declared a yellow fever epidemic on August 23rd, Memphians fled. Some people sold their prized possessions, silver watches, jewelry to raise the money to leave. Others emptied their bank accounts. People left town any way they could, “By hacks, by carriages, buggies, wagons, furniture vans and street drays away, by bateau, by anything that could float on the river, and by the railroads, the trains on which, especially on the Louisville Road, were so packed as to make the trip to that city or to Cincinnati, a positive torture to many delicate women every mile of the way. The aisles of the cars were filled and the platforms packed. The stream of passengers seemed to be endless, and they seemed to be as mad as they were, many.” More than half of the city’s 50,000 residents got out. Some went to the country. 5000 people lived in temporary camps in Shelby County. Other people escaped to cities presumed to be far enough north to be out of the reach of yellow fever. St Louis, Cincinnati, Detroit, Chicago. Many communities, though, especially the smaller ones around Memphis, imposed quarantines to keep those Memphians out. Quarantines weren’t an unreasonable response, as fleeing Memphians carried yellow fever to some of the places where they sought sanctuary. Within days, the city’s bustling city streets turned desolate and business ground to a halt. The disease spread swiftly among the 20,000 who were left behind. “The king of terrors continues to snatch victims with fearful rapidity, the newspaper, The Avalanche, reported. The mood turned desperate. Officials spread lime and carbolic acid on streets and sidewalks to douse the smells. Keating, wrote, “An appalling gloom hung over the doomed city. At night, it was silent as the grave. By day, it seemed desolate as the desert. The solemn oppressions of universal death bore upon the human mind, as if the Day of Judgment were about to dawn. The energies of all who remain were enlisted in the struggle with death.” As the casualties accumulated, signs of loss were impossible to hide, The small burnt piles of bedding that are seen on every street, but tells the passerby ‘a death has occurred here.’ These blackened spots are growing in number daily. Help poured in from across the country. Trains dropped off carloads of food, clothing and coffins. People collapsed and died on the street. Many died at home alone, only to discover later in advanced states of decomposition. A man named Rivier was found in his home naked and alone with flies swarming around him. The entire Gregg family, both parents and six children, died in a matter of days. The Memphis Appeal wrote, “One of the remarkable features of the disease as it prevails now, is that whole families have been swept out of existence, father, mother and children have followed each other in rapid succession to the grave, and in some instances, several members of a family are lying dead at the same time, having died almost within the same hour.” One of the casualties was Jefferson Davis Jr, the son of the former Confederate President. The disease also took prominent merchant Nathan Menken, one of the city’s wealthiest and most generous men. After he died, his body had been dumped on a pile with other victims. The family asked the undertaker, Louis Daltroff, to sort through the stack of corpses and find Menken’s body so they could bury him according to the traditions of his Jewish faith. Daltroff did just that. No funerals were held while the epidemic raged. It’s unlikely they would have been well attended anyway. Keating wrote “The luxuries of woe were disposed with.” Burials continued, though, of course, and the work was nonstop. The Memphis Avalanche reported, “The county undertaker has four furniture wagons busy all day. Upon each, the coffins were piled as high as safety from falling would permit. These four great vehicles doing the wholesale bearing business failed to take to the potter’s field, all of the indigent dead. Empty streets and stores, the stench of rotting corpses, the constant parade of wagons carrying bodies to be buried. It was too much for people to bear.” Father Dennis Quinn later recalled the chilling sense that, “The most dreadful sense of horror was the fact that in a short time, these ghastly sights would fail to inspire terror.” By mid September, fatalities peaked at 200 people a day. The end of the epidemic came, as it typically did with the season’s first frost. Reverend Quinn recalled, “A heavy black frost was the pleasing spectacle that gladdened the sight of the many who were on the lookout for it. This harbinger of returning health to Memphis caused unalloyed joy.” A few days later, the Memphis Board of Health declared the epidemic over and invited people to return. With the crisis over the city took stock of its losses. Of the 19,000 who stayed behind, mostly people who couldn’t afford to leave, 17,000 had contracted yellow fever, and over 5000 died. The toll included half of the city’s physicians, a quarter of the police force, and two dozen firefighters. Not everything about the epidemic turned out to be bad news, though, John Thomas and Beatrice Johnson met while helping people afflicted with yellow fever. They fell for each other and got married after the epidemic ended. In spite of the reassurances from health officials, 1000s of people never returned to Memphis, starved of revenue because of the sudden, dramatic loss of population, the City government was no longer able to pay its bills. In 1879 City government dissolved, and the state of Tennessee assigned municipal governance to a special taxing district. That summer, Memphis had another yellow fever scare. 587 people died, and the taxing district announced plans for an ambitious program to aid in improving public sanitation, which included construction of a state of the art sewer system. It took a while, but Memphis bounced back. The city did not suffer through another yellow fever epidemic, and people began moving to the city again. After seeing its population drop from around 50,000 in 1878 to 33,000 just two years later, the population grew to 64,000 over the next decade. Yellow fever is no longer a threaten in North America. The last significant outbreak in New Orleans was 1905. Aggressive efforts to control the mosquito population successfully tamped down the disease. There’s still no treatment for yellow fever, but the risk of a new epidemic is very low today, thanks to the development of a highly effective vaccine, a single shot provides lifetime protection for 99% of the people who are innoculated. While we may love complaining about mosquitoes in North America, we’re lucky that mosquito bites are merely annoying. For many people around the world, preventing mosquito bites remains a matter of life and death. But what are the best ways to keep mosquitoes at bay? There are many folk remedies that are believed to keep the bugs away, but only a handful of repellents are proven to work. As Timothy Flint described in his work, “Burning something stinky that creates a thick smoke, a smudge, as it was sometimes known, was a common deterrent well into the 20th century.” It was a pretty effective way to keep the bugs away, except for the fact that you had to be immersed in the smudge yourself for it to work. Maybe that’s where the mosquito dose came in. Not that it kept the mosquitoes away, it didn’t, but maybe it just made you care less about the buzzing, the bites and that nasty smoke. When it comes to repellents, the only chemicals that are proven to work are picardin, lemon eucalyptus oil, deet and citronella. The amount of time they work varies depending upon the chemical and its concentration. For example, a repellent with a 5% concentration of deet will keep the mosquitoes away for 90 minutes, but repellents with a 10% concentration of citronella only work for about 20 minutes. There’s a new weapon in our battle with mosquitoes, though. Genetic engineering. Researchers have developed a fungus to infect mosquitoes that shaves a couple days off their eight to nine day lifespan, which is enough to keep the malaria causing plasmodium parasite from developing to maturity. A company in Brazil inserted a gene into male mosquitoes that they pass on to their larvae. After they hatch, the gene causes explosive growth of a protein that kills them all. When it was tested in Mandacaru, Brazil, an area with a growing epidemic of mosquito borne Dengue fever, the mosquito population dropped by 96% in six months. We may have the means in a few years to completely wipe out the world’s population of mosquitoes, but should we? Would we miss them? Even though mosquitoes have been around for about 50 million years, far longer than us, biologists have been hard pressed to figure out if mosquitoes matter. They aren’t a critical food source for any creatures anywhere. They don’t seem to play a linchpin role in any ecosystems that we can identify. One person, writer David Quammen asserted that mosquitoes have kept us humans from populating and destroying tropical rainforests. Even if that was a deterrent in the past, it seems much less so today. So would we really miss mosquitoes? Personally, I’ve reached my own detente with mosquitoes. I won’t let them stop me from taking the hikes I want to take, and I don’t feel the need to continually swat and swing my arms as long as they stay off my face. I rarely cover my skin with bug spray. Instead, I wear a long sleeve shirt, pants and a hat. It’s not very sexy but it works. And if that fails, I might opt to take a mosquito dose after my hike. It may not keep the mosquitoes away from me, but it sure does mute the sting. I’m one of those lucky people who find mosquitoes merely annoying, so I don’t feel enough animosity to wish them out of existence, but I would probably feel very differently if I lived in a place where many of my friends and family were dying from diseases transmitted by those little monsters. And now it’s time for the Mississippi Minute. Well, this was a different episode than I normally produce for this podcast, so I would love to know what you thought about it. I’d also love to know what you think about mosquitoes and how you’ve come to learn to live with them. All of us have to deal with them at some point if we’re going to be outside, so maybe we all have slightly different ways of handling that. Do you take a mosquito dose? Do you cover yourself with a spray like OFF!? Do you just not go out? You know what? What is your what is your view on that? Do you think we should wipe out mosquitoes if we have the technology to do so? And if you have some really fun or harrowing mosquito stories, please, please feel free to share those as well. I would. I want to hear it all. So don’t, don’t hold back on me. So go ahead and head to MississippiValleyTraveler.com/podcast. You can contact me there. You can leave a comment on the episode, or you can drop me an email at dean@travelpassages.com. Thanks for listening. If you enjoyed this episode, subscribe to the series on your favorite podcast app so you don’t miss out on future episodes. I offer the podcast for free, but when you support the show with a few bucks through Patreon to help keep the program going, just go to patreon.com/deanklinkenberg, if you want to know more about the Mississippi River, check out my books. I write the Mississippi Valley Traveler guidebooks for people who want to get to know the Mississippi better. I also write the Frank Dodge mystery series that’s set in places along the river. Find them wherever books are sold. The Mississippi Valley Traveler Podcast is written and produced by me, Dean klinkenberg. Original Music by Noah Fence. See you next time you.