In this episode, I talk with wildlife biologist Mark Vukovich about the unique area known as Snake Road. Located about 40 miles south of Chester, Illinois, Snake Road passes through the LaRue-Pine Hills and Otter Pond Research Natural Areas. It’s an area full of surprises any time of year, but it’s best known for a few weeks in spring and fall when snakes move between the bluffs and nearby wetlands and the paved road is closed to protect them. In this episode, Mark talks about this unique ecological area and the 22 species of snakes that make it home. He offers tips for when to visit and how to be a respectful visitor and describes a citizen scientist project that he started. Mark also has responsibilities for forest management in the area, so we talk about the forests of that area, past and present, and the birds they attract. He offers a few thoughts to help identify migrating birds in the fall, when they may look and sound different from other times of year.

Show Notes

Support the Show

If you are enjoying the podcast, please consider showing your support by making a one-time contribution or by supporting as a regular contributor through Patreon. Every dollar you contribute makes it possible for me to continue sharing stories about America’s Greatest River.

Don’t want to deal with Patreon? No worries. You can show some love by buying me a coffee (which I drink a lot of!). Just click on the link below.

Transcript

49. Mark Vukovich on Snake Road and Birds

Sun, Sep 22, 2024 3:59PM • 1:13:08

SUMMARY KEYWORDS

snake, species, area, birds, road, good, larue, place, people, forest service, cliffs, biologist, shawnee, mississippi, bird watcher, dean, pine hills, forest, duck hunters, love

SPEAKERS

Mark Vukovich, Dean Klinkenberg

Mark Vukovich 00:00

22 species of snake. Some of those are western species, like the western ribbon snake. And then you got the it’s kind of like the northern extent of northern cottonmouth that goes, they go a little bit further north, and then southern hognose is there.

Dean Klinkenberg 00:43

Welcome to the Mississippi Valley Traveler Podcast. I’m Dean Klinkenberg, and I’ve been exploring the deep history and rich culture of the people and places along America’s greatest river, the Mississippi, since 2007. Join me as I go deep into the characters and places along the river, and occasionally wander into other stories from the Midwest and other rivers. Read the episode show notes and get more information on the Mississippi at MississippiValleyTraveler.com. Let’s get going. Welcome to Episode 49 of the Mississippi Valley Traveler podcast. I love it when random events spark ideas on what to bring you for future podcasts. And I had one of those random events happen this past spring. I was down on Snake Road, walking along the road during their spring closure, and I bumped into Mark Vukovich, who is the biologist for the area. We had a lovely conversation standing out there that spring, and I thought we ought to do this on the podcast. So so we did, and that’s what’s going to be in this episode. Mark Vukovich is the biologist for the US Forest Service, and his domain includes Snake Road and other parcels in that area. They’re technically known as LaRue-Pine Hills and Otter Pond. We get into that during the podcast. So in this episode, we talked about his path into biology. We talk about what makes that area around Snake Road so ecologically interesting. And we get into some tips for visitors, including things like, what’s the proper etiquette? Here’s a quick hint, never try to pet a snake. Also some ideas about when you might want to visit, what to expect different times of the year, and we get into some of the habits of snakes themselves. So it’s a really interesting conversation. I think you’ll find some useful tips from that. Mark also talked about the program he started to help to enlist volunteers to help collect data on the snake population in that area. And so he’ll you’ll hear a little bit about that as well. We had some extra time, so we really got more toward what his his first passion was, and that’s bird and forest. So he’s responsible for some forest management in that area. So he tells us a little bit about how the Forest Service is dealing with the legacy of all the introduced pines in that region of southern Illinois, the birds that one can expect to see in different times of the year, with some specific tips on how to spot birds this fall, since we’re now in the fall migration season. Talks a little bit about the historic forest cover in Southern Illinois and how it’s changed over time. And we have a little conversation about using technology to help help out with forest management and with just learning about the outdoors. Mark is a very passionate man. He loves what he’s doing, and I think that will come across in this conversation. And I think this is a fantastic area, like I go down to Snake Road just to enjoy the wetlands and the bluff communities, just for the beauty of that particular area. So even if I don’t see a snake when I’m down there, it’s always a worthwhile visit, as always. Thanks to those of you who show me some love through Patreon. Your support keeps this podcast going and it makes me smile. For as little as $1 a month, you can join the Patreon community, which includes getting early access to podcasts, something you might enjoy. If you’re not into the Patreon thing, you can buy me a coffee. So if you want to know about either one of those things, just go to MississippiValleyTraveler.com/podcast, and you’ll find links there for Patreon or just to buy me a coffee. And at that same address, you’ll find a list of all the previous episodes, all 48 of the previous episodes, and you can click on the episode you’re interested in and also see the show notes. And now let’s get on with the interview. Mark Vukovich is a wildlife biologist with the US Forest Service, who I just happened to meet walking around Snake Road in Shawnee National Forest a few months ago, and naturally, that led to a podcast invitation. So welcome to the Mississippi Valley traveler podcast, Mark.

Mark Vukovich 05:11

Yes, thank you, Dean, thanks for inviting me.

Dean Klinkenberg 05:14

It’s a pleasure to have you on here, and I just want to kind of spend some time hearing about your experiences and that little that part of Shawnee forest. But before we get into that, tell me a little bit about how you got interested in biology and your path to becoming a wildlife biologist.

Mark Vukovich 05:32

I did my undergraduate degree at University of North Carolina in Asheville, which is in the mountains of North Carolina, and I, I literally just went into ecology class, and it was probably near the end of the end of the semester, and the professor introduced to everyone how biologists survey birds. And it was a, it was a handout that we read and, and I was reading it, and these guys and gals were identifying birds by sound. And I was like, how, you know, that was my first introduction to them. How are they doing that? And I just scratched my head. I’m like, That’s impossible, because I had all at that time in my life, I was doing a lot of different things. I was playing guitar. I was, you know, I can, you know, I was conquered, you know, I was challenging myself to I was running, you know, I was and I, after the class, I went and talked to the professor and asked her where I can get the recordings for for bird sounds. And she’s oh, Malaprop’s downtown Asheville. She just like, nonchalant. I’m like, Well, next day, or maybe it was even the same day I got on my mountain bike and I rode into downtown Asheville. This was back in the 90s when Asheville was not like it is now, and you could ride your bike safely into downtown. And so I bought the CDs, and I don’t even think they sell CDs anymore, and that’s where it began for me. I came back to my my dorm apartment, I was living on campus, and I started listening, and one bird that that sprang out to me was in eastern wood pewee, which is a really simple whistle fly catcher. And I was like, I’ve heard that bird. And from there, I just went absolutely berserk. I became a bird guy, and then I pursued a master’s degree at Eastern Kentucky University with Gary Richardson, who is now retired, and I wanted to work with him. He’s an ornithologist, and that was it. I just birds was it. I didn’t look, I didn’t look to see, like, Well, are there jobs? How much money will I make? I just, I just wanted to do it. I just like, This is what I got. This is what I want to do, even without, without knowing, right? You know, when you’re in your late, mid, mid 20s, you know you you just, you still got a lot to learn, and it’s all worked out for me, though I had a good master’s degree project there, and then I, I followed my wife, who was doing a PhD at Clemson, and I got a job with the Forest Service on the Savannah river side, research, Forest Service Research, and then that culminated into a permanent position there while she was doing her PhD. And then I was there for 14 years, and then I moved up here. Moved up to take a big job on the Shawnee National Forest, and that’s basically the lead wildlife biologist. I would, I would call myself like the Endangered Species biologist for the Shawnee National Forest.

Dean Klinkenberg 09:17

Cool. So when you were a kid like, Were you the kind of kind of kid outdoors a lot, playing to the woods or fishing or…

Mark Vukovich 09:23

Yes, yeah, yes. So I grew up in the in the early 80s, late 70s, Jacques Cousteau was on TV. My dad was a scuba diver and a scientist, and we watched, there was only like, you know, back then, there was only a few programs on TV, Jacques Cousteau and Star Trek and and I my brothers. I had two I have two brothers and a sister. I was the youngest. And we, we would do reenactments of Jacques Cousteau, like in the house. And, yeah, I just. Grew up in a kind of a time in Raleigh, North Carolina, where it wasn’t fully developed. And, you know, they were building subdivisions, and basically old farmland that had grown up. And so there’s redhead woodpeckers, um, blue jays, you know, things like that that I didn’t really identify until later on, when I became a bird guy. I remembered him, and I used to go fishing. There was an old there was a golf course, really fancy one, and I would go fishing in the ponds there, and they were excellent for bass. And like, their security would, like chase me off the golf course and stuff. I would hide in the bushes, and then they would drive by, and then I’d go back fishing and so, and I grew up with friends, you know, we would go out and fish all day. So, yeah, that’s basically how I I grew up in kind of, kind of in the suburbs of Raleigh, the early suburbs of Raleigh.

Dean Klinkenberg 10:59

Yeah, I was a suburban kid too, and I wasn’t trespassing on the golf courses or anything to fish, but we had some woods nearby, and I spent a lot of time wandering around the woods and seeing what I could fish out of the creek with my hands. And,

Mark Vukovich 11:13

Oh yeah.

Dean Klinkenberg 11:14

I guess, you know, nowadays we kind of joke about free range kids, and I to me, that was just how we grew up, right?

Mark Vukovich 11:20

Oh yeah. I think our the I’m 50 years old, our generation, yeah, we were, we were kind of like, where’s Mark? You know, my, my mom used to ring a cow bell like it’s dinner time. And hopefully I was within hearing distance to hear that. But, and I had, I had a neighbor that really was implement, influential. She, she had, she was married to an old southern man who was a World War II vet. And they had every animal that you could, every pet that you can imagine. They had a pet gray squirrel that they kind of, they that was orphaned and they raised in their garage. They had bird, they had a bird, they had aquariums, they had snakes. I used to go and play with their son, and we would take magnifying glasses and like, wreak havoc on ants. Yeah. So it was, it was good. It was good upbringing, and a lot of freedom, and, you know, interaction with with good people, right?

Dean Klinkenberg 12:27

And I bumped into you when you were kind of surveying Snake Road. So it sounds like you still get to spend a good chunk of your time outdoors.

Mark Vukovich 12:36

Yeah, yeah, yeah. It’s, it’s challenging, because when you move up in a position, you know, you end, you know, these days, you end up right here behind a computer and doing meetings and and and reports. But so far I I’ve still kind of maintained that 50/50 and I think the key is to kind of demonstrate to leadership and to your to your colleagues that, yeah, I should probably be, you should I should probably be outside, because I can find things and see things that other people can’t.

Dean Klinkenberg 13:12

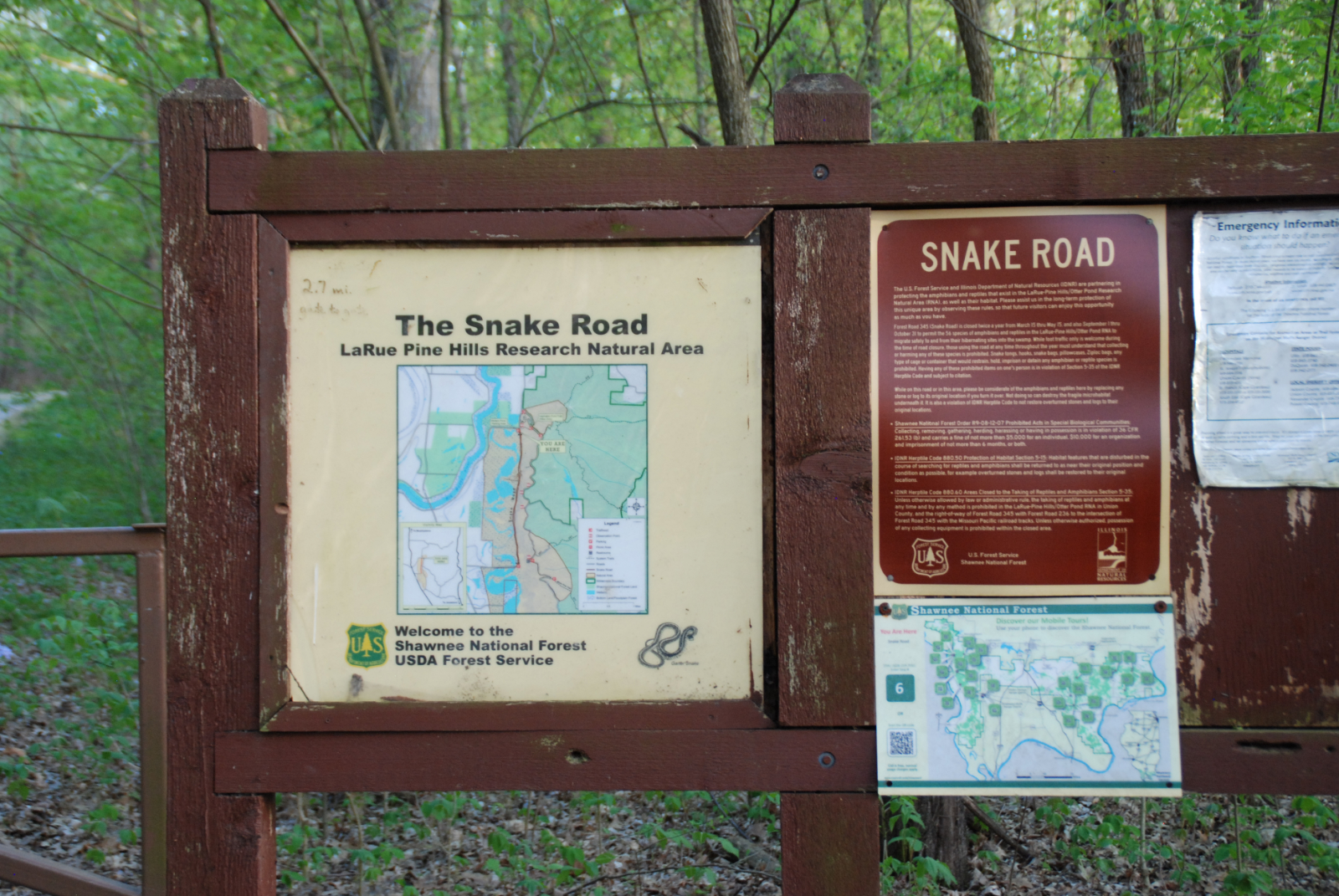

Yeah, well, well, let’s talk a little bit about Snake Road specifically. First, I know we colloquial, know the area as Snake Hills, but it’s technically, it’s what LaRue-Pine Hills, the name of the area.

Mark Vukovich 13:24

Yeah, there. There’s basically two research natural areas that are right, like, right together. It’s a LaRue-Pine Hills research natural area and Otter Pond, research natural area, which is the southern end of Snake Road, and I think it’s around 2000 acres, when you put it all together, 2300 acres, or something like that. And it’s a, it’s a designation that the Forest Service created years and years ago, and it’s a special designation, and it was meant, it’s mostly meant for research, to promote research and education, and because they had this grand vision of, like, all these researchers coming there and and and working there, and they have, and there has, there is a good history of research at LaRue, but it is definitely dwindled down in the last 10 to 15, years. I mean, I still get requests to do research there, but it’s not, it’s not much, and a lot of that has to do with funding overall in universities and things like that. And we don’t have the Shawnee doesn’t have a research station department add on. They are located in Missouri, and they have a tendency to work on Mark Twain more, but they’re starting to expand, and they do some other things, not on at LaRue, but one of our management areas in Hardin and Pope County. So they just don’t focus on LaRue. So a lot of the a lot of the vision to create these designated areas, they’re good, and we do get some pretty good research, but it has, it has dwindled, and I personally like to see more. It’s just, it’s all dependent on on funds.

Dean Klinkenberg 15:20

Yeah, absolutely, it’s interesting. So I guess I didn’t realize that that was kind of the genesis of that area and that designation, because it seems like it’s kind of become more of, I wouldn’t necessarily say, recreation, but it draws a lot of a lot of people from the public who just like to go down there and walk around and check the place out. So it almost seems like that public access has kind of become more prominent than the research.

Mark Vukovich 15:47

Yes, Dean, you’re absolutely right. And another thing about LaRue is it borders a wilderness area, so it’s but what I don’t one of the things I don’t like about is right to the west of it’s all private land. So it’s right on that, right on the peripheral of a lot of private land. And, yeah, it’s in the old days. If you look at some of the historical documents of the place, the duck hunters own that place because it was a, it’s an old oxbow from the Big Muddy that, you know, they brought the they they made that levee road, so that kind of stopped a lot of the flooding that naturally occurred there. And luckily, it’s spring fed from the limestone cliffs, still, but I would like to seen it before the levee road. They put the levee road there, but it has been there for so long that the ducks, you know, for 1000s of years have always viewed it as a stopover point, and so it’s always been really good for ducks. And in the early days of the Forest Service, you know, before NEPA and environmental laws, yeah, the duck hunters are like, Hey, we love this place, you know, the St Louis duck hunting club. Can we build some dams out here and, like, you know, and and make some better duck holes for us to shoot ducks? And you know, they’ve it’s pretty interesting to read some of the old historical documents there about that. And then over time, it’s evolved. It’s pretty interesting. There’s still a good contingent of duck hunters that go there, but over time, now it’s become more non game focus and enthusiasts with snakes and the the the genie is out of the bottle there, in terms of Snake Road, with publications and and YouTube. I mean, go on YouTube, there’s so many videos now, people go out there and do their own thing, and they publish it, we, you know, and they have all the right to do that. It’s First Amendment. And so, yeah, now, now we try to kind of manage that, because the purpose of the research natural areas was education and like, kind of like limit rec activities, but they didn’t put it in that document. How to do that? How to how do you limit? You know, because it’s open, it’s public,

Dean Klinkenberg 18:18

Right. There’s no way to control access, except for even restrict cars, but that’s about it,

Mark Vukovich 18:24

Yeah. And even if we did that, people would still go.

Dean Klinkenberg 18:29

Right. They’d still find a way.

Mark Vukovich 18:30

Yeah.

Dean Klinkenberg 18:32

Tell us a little bit about sort of the ecological communities there, though, like, I think it’s really a beautiful area, and we’ll talk about the snakes in a minute, but I’ve probably been there a dozen times, and then maybe half those times I’ve never seen a snake when I was there, but I still had a great time, because it’s such a beautiful, interesting ecological area. So tell us a little bit about what, what the community, ecological communities are like there.

Mark Vukovich 18:56

Well, the easiest thing I like to say for the public, because not everybody’s biologist, or an ecologists, it’s basically that areas where north, south, east and west all come together and and it’s an old oxbow swamp with those cliffs, and it’s just a unique situation. So you have all these and it one of the most diverse places on the forest for plants, if you’re a botanist, it’s a great place wild flowers in in the spring, there’s a lot of diversity. And I’m not going to get into it, because I am not a botanist. It is an excellent place for if you’re a botanist, because it has cliffs and so there’s cliff dwelling species growing on the on the rocks there, and then it it goes right down into a swamp, and you have swamp species. It’s just a really interesting, unique place because of that oxbow and those cliffs.

Dean Klinkenberg 20:00

And I imagine, because of that, it it has also it supports a pretty wide range of wildlife as well, not just flowers, but animals as well.

Mark Vukovich 20:08

Yeah, So 22 species of snake. Some of those are western species, like the western ribbon snake. And then you got the, it’s kind of like the northern extent of northern cottonmouth that goes, they go a little bit further north. Yeah. I mean, it’s and then southern hognose is there. Mississippi green water snake, which, that’s a species where I’ve met a gentleman that flew from Colorado Springs to St Louis, rented a car and was staying three nights at Cape Girardeau. Just to photograph of Mississippi green watersnake. He was like a bird watcher.

Dean Klinkenberg 20:49

Wow.

Mark Vukovich 20:49

He’s just like a bird watcher. He just, and he had a huge camera, and it was really funny conversation, because we were talking about it, and I’m like, there’s one right there. He’s like, Oh, you know, he starts taking pictures, and I totally forgot I was there. I just kind of like, Alright, have a nice day. I walked away. So, yeah, it’s really, it’s really a fun and easy access spot, if you’re a snake watcher. And it’s been, it’s been fun, it’s been interesting. You know, I see 99% of the people there are doing what we want. They are walking and photographing plants and animals. And it’s just been really, it’s been fun seeing it. I had heard about the road before I took the job. My wife had taken some of her students there to to go walking during the prime time. Yeah, and it’s just a really popular place, like you said, it’s just as much about people than it is the snakes and and the wildlife there.

Dean Klinkenberg 21:55

Yeah. So what is it? So I’m going to guess that all of those. You said 22 different species of snakes live in that area. Yes, they can’t all be eating exactly the same thing either then, like, there must be a pretty good diversity of other kinds of reptiles or amphibians, or frogs or whatever that all the snakes are feeding on.

Mark Vukovich 22:21

Yeah, that’s right, you know, you have king snakes that are eating other snakes, and then you have cottonmouths that are eating fish. Then you have rat snakes that are eating mammals, and maybe other small snakes. And then you have rough, green snakes that are eating, you know, small amphibians and insects. Yeah, it’s, it’s, it’s a really interesting place where all these species intermingle right there.

Dean Klinkenberg 22:50

So we’re in the middle of the closure now, like twice a year, the road is closed on car traffic for two months at a time, and right now, but September one through the end of October is the fall closure.

Mark Vukovich 23:03

Yeah, and I’m, I’m kind of, I’m going to extend it right up until the duck season, I think from here on out, because it’s getting warmer. So we’re adaptive, and it’s called adaptive management. So last spring, we had the earliest closure there ever? I think we closed it in February, like three weeks before the regular closure, because it was so warm. And then we have such enthusiastic locals that basically live there. I joke they live there in a one lives in a cave up there somewhere, and they, they informed me that snakes are coming out, and I reacted quickly. And we, we closed the gates, and we saw a really big push of of snakes, a really, really early in the season. And I started a volunteer program. There a citizen science or it’s now called community science program, along with an app that you you can get on your phone to collect data for us to to to put in the coordinates of of the snake that you see, take a picture of the snake, and then upload it to our server, and I can analyze the data and kind of inject weather data and temperature data and things like that. And they also kind of get give us an idea of public visitation. They count cars and people to give us an idea like so we’ve learned, like, the weekends are obviously the busiest time, and the weekends are typically people, the public’s first visit to Snake Road, like, oh, you know, yeah, we traveled here. We’ve heard about this place. We wanted to check it out. It’s always on the weekends. So a lot of the locals hate the weekends, and they’ll they’ll be out. During the week, and it’s interesting. And even when the people that are new to it and they walk the road, they’re very similar to you, like, they might see one or two snakes or no snakes, and they’ll still say, like, this is a pretty interesting place, these cliffs and swamp and the gentle road, that’s one thing I like about it, that road is not difficult to walk. There’s a couple gentle hills there, but it’s not bad, right? Um, and, and then just the friendly nature of a lot of the people there, because you’ll, you’ll walk, and they’re like, Hey, how’s it going? And you know, if there’s a snake on the road, there’ll be a whole bunch of people, you know, taking pictures and video, and like, Hey, what’s this? And like, Oh, look at this. It’s, you know, it’s a king snake or a rattlesnake. And, you know, a sense of community and and enjoyment of nature. It’s, it’s been really great for us because, you know, with this volunteer program, because we are engaging people in our national forests and we’re educating them, you know, through the app. You know, we every year, when I get all the data, I try to at the at the end of the season or the next season, I kind of do the results of the last season. You know the show, this shows the volunteers that, yes, we’re using this data to inform management and to learn about this population of snakes here.

Dean Klinkenberg 26:30

So where would that be available? Where do you post that or share that to?

Mark Vukovich 26:34

Well, that’s the thing, Dean, I don’t we don’t share it yet. It is free. I mean, if somebody requests it, I I’ll give it to you, um, but, like, locations of the snakes, things like that, I kind of don’t want to give that up, right? Um, because some of them are, are state protected, right? And I can’t give them up. I believe I’m pretty sure about that. And one of the reasons why I started the volunteer program is the illegal pet trade. I’m worried about that we we have seen, we’ve had incidents with that, with and law enforcement acted quickly. And so that’s one of the reasons why I started the volunteer program, and then the other one was snake fungal disease, which is attacking some of the snakes and causing population declines in several species. And it is there. We suspect that it is there at snake road. It’s in Johnson County. So if it’s in Johnson County, it’s it’s it’s more likely in Jackson County, it’s everywhere it it’s kind of like white nose syndrome with bats. It’s a fungus that is attacking snakes. So these were two, two things, two issues that, really, you know, cemented me. I need more eyes on the ground. And I have, you know, all these great locals that are there all the time. Why not help me? I can’t, you know, I can’t be everywhere all the time. And it’s working out really great. I It’s been fun, and I want to keep it going. And it’s getting better every season. We we get more data every season, and more volunteers, typically, every season.

Dean Klinkenberg 28:21

Well, let’s talk about basically what’s going on here, too. So I always forget this like snakes, are they true hibernators?

Mark Vukovich 28:29

Oh, that’s good question. No, they’re cold blooded, so they’re not. They’ve pretty much just shut down and the they’ll, their system will act kind of like antifreeze and just, you know, but a lot of times they do freeze up, but they just, they can just come right back to life. And so, yeah, so each year, the snakes come out of the cliffs, go into LaRue swamp and elsewhere. And then when the weather starts getting cold, they go back into the cliffs. And it’s a really interesting phenomenon that’s been going on for 1000s of you know, whenever those cliffs were were created, right? I would, you know, I always tell people I would love to get Doc Brown and DeLorean with the flux capacitor, and go back 300 years and see what that what it was really like. I bet it was kind of like, you know, Indiana Jones kind of thing, where the whole fourth floor was pretty much covered up in snakes, because from from those cliffs to the river to the Mississippi River was probably all bottomland, hardwood forest, and it was probably a phenomenal event of snakes.

Dean Klinkenberg 29:50

With those mixed in ponds and wetlands and old oxbows.

Mark Vukovich 29:55

It was probably a remarkable phenomenon to behold. Yeah, of course. Would probably die just getting there, because I’m sure the swamp was pretty impenetrable or very difficult to maneuver in to get to that point. And that road was, you know, not there. You know, they were going to mine those cliffs, if you read some of the old documents. The road was put in before the Forest Service. It was designated forest service land, and there was proposals to mine those limestone cliffs that never went forward. And I can’t imagine, you know, them destroying that place, right? I’m happy that they didn’t and and we got, we get, we get to see these, these cliffs in this place. It’s a great place. I mean, I there’s owls. Owls use those cliffs. A lot of, a lot of stuff uses those cliffs. Vultures use it.

Dean Klinkenberg 30:59

So, so the road is closed because it’s this barrier between the cliffs and the wetlands. So the snakes will winter in the protected area, maybe find a nice little niche somewhere in the cliffs where they can survive the winters, but then they have to go back to those wetlands to to feed on the other side of the road. So that’s why the road gets closed a couple times a year, to protect that migration. I don’t know that we think about snake migration as a thing, but they’re not going real far, but they are moving from one place to another.

Mark Vukovich 31:32

Yeah, I don’t, I don’t think it’s a migration. It should, the proper term should be movement, yeah, not really migration. And nobody’s done rated telemetry on some of these snakes. I mean, obviously some of these snakes are too small to put a transmitter in, but some of the bigger ones you could, and you could figure this out, like, how far do they go? But once again, that’s, that’s on my bucket list. I’d love to have a researcher come up with that proposal and and get the funding to do it, I would all, I would be all for it on a few species to figure out how far they really, truly moved from that area.

Dean Klinkenberg 32:12

That would be fascinating.

Mark Vukovich 32:16

And hibernation, and hibernation, you know, like, there’s warm winter days and snakes will come out. And so that’s, that’s why it’s not really true hibernation for them. And they just kind of just shut down and, you know, you just get the right temperature. And they’re, they’re up in February. They’re like, okay, it’s, it’s time to go.

Dean Klinkenberg 32:37

So if we have a warm day in December, will some of them come back out too?

Mark Vukovich 32:40

Oh yeah, yeah. Some locals are out there all the all year round, and they’ll see them. They’ll be moving in there. They won’t be very far from the cliffs. I mean, they’ll maybe poking their head out, but they’ll be, they’ll be awake in some of those circumstances.

Dean Klinkenberg 32:59

So let’s go through a few practical tips for folks who are thinking about going down there. Like, I know there’s a small parking area at the north end of Snake Road that there’s also access from the south end, but I don’t remember a lot of parking there.

Mark Vukovich 33:14

Yeah, that’s, that’s, we don’t have a real good parking area. You just park on the side of the road. Get out of the way so vehicles can drive in and then turn around at the gate, and then there’s a little road that takes you to otter pond that duck hunters and kayakers like to use to put in. And so you could theoretically park down there, but it’s a really narrow road, and there just isn’t space for a parking area there.

Dean Klinkenberg 33:45

So in terms of when to visit, like, have you noticed much of a difference between the time of day? Like, if you want to, if you’re specifically interested in spotting snakes, is it better to go earlier in that movement season or later or morning versus evening? Or have you noticed? Or is it just better to go when it’s warm?

Mark Vukovich 34:05

Okay, so there’s two seasons, and they’re each really different. Um, in the fall, typically October, you know, especially like mid to late October, that’s when there’s a final push to get into the cliffs. But it’s variable with the temperature. You know, we could have a really cold October. And so I tell people to watch the weather. You know, weather and weather and animals are really especially cold blooded animals is really important. Most people come in the afternoon. They’ll, you know, there’s like us, you know, like regular people, they want to have coffee, and then by the time you get there, and that’s the nice thing about this place. It’s pretty easy to access off the highway there, but yeah, typically it’s like 11 to 2 to 3 is a really busy time, but you can still see some. And early in the morning, I know some of the micro snakes, like the dekay’s brownsnake and and ring-neck snakes, you know, you can see them early in the morning moving. You gotta, you gotta watch the road. You gotta because they’re so small. And we’ve learned that with the app, you know, because we’ve had some volunteers go early in the morning. They see these micro snakes more often. So that’s the really usefulness of having a volunteer program. You got more eyes that are going at different times of the day that can kind of shed light on these patterns of of times of when, when is a good time to see certain species and where, because we are getting coordinates of of their observations, maybe some of these species. There’s like, one section of the road that’s really good. And so, and in the spring, it’s the opposite, like April. So we close, we close in March, mid March. And it’s typically April, but this past year, it was late February, March was the time to go. But there’s, you know, some species take a while to come out, like timber rattlesnakes, late April, mid April, um, and so you just have to, you just have to, kind of read up on these species. And that’s yet another reason why I wanted to do an app, because I kind of view it as our responsibility. Like, okay, this is when you see it, and we have the data right here to show you, um, but I need a lot of data, and we just started doing this. This will be our second fall season using an app. We started with data sheets, um, but now we’ve got an app, and it’s been going well. I think, I think in about five years, we should have a pretty good idea, as long as we have continued effort, which I think we will

Dean Klinkenberg 37:06

Can anybody participate in that then? How can people become, that want to contribute to that?

Mark Vukovich 37:11

Yeah, so this good question. Dean, thanks for asking. We started a hybrid, like, meeting or so we we do a workshop. So we’ll take volunteers, and we advertise for volunteers on our social media site. And we have been trying to figure out, because, in the past, we’ll have a workshop at the Forest Service office in Jonesboro. But you know, we have restrictions there with fire marshal. If you can’t have 50 people in this little building, right, right? And so we’ve we did a hybrid this year, virtual and and in person and to in hopes of expanding and getting people just to come to the workshop virtually. So we would bypass having a bunch of people in one place, and then go over species identification, the objective of the program and introductions. A lot of the our, lot of our volunteers are retirees, and they come with that generation where they like to meet people. They like a sense of community. They want to see people and come, come in and and have a drink, you know, and talk and tell stories. But at the same time, we have a lot of young people starting to come, and they are like this. All their interactions are on screens. And so it’s, it’s really, it’s been fun. It’s, it’s interesting. So we try to hybrid this year, and that’s why I think it’s, it’s going to work as as long as we keep it, you know, keep it going and and maintaining the app, and improving the app, but also reporting the results of their work. I think that’s really important, and a lot of that responsibility is on me and the other biologists to to report that work, maybe even publish it, and maybe get a researcher to take the data and run with it and do some statistics and quality well, you need quality control, because with all citizen science or community science, there’s going to be errors. Which is, okay, that’s expected, but, yeah, I think it’ll I think it’d be really interesting and help define certain times, maybe, if you’re interested in seeing certain species. But overall, I think it’s really good for the snakes, because I get to, as a wildlife biologist, monitor that population over time, make sure that it’s healthy and doing well, and how it’s changing with, say, like climate change, maybe, maybe they’re coming out earlier now than they did 10 years ago. You know, things like that.

Dean Klinkenberg 40:00

Hey, Dean Klinkenberg here, interrupting myself, just wanted to remind you that if you’d like to know more about the Mississippi River, check out my books. I write the Mississippi Valley Traveler guide books for people who want to get to know the Mississippi better. I also write the Frank Dodge mystery series that is set in places along the Mississippi. My newest book, “The Wild Mississippi,” goes deep into the world of Old Man River. Learn about the varied and complex ecosystem supported by the Mississippi, the plant and animal life that depends on them, and where you can go to experience it all. Find any of these wherever books are sold. I think it’s a great model. So I wish you the best with that. I’m sure you will be able to find funding at some point to ramp it up to it just seems like it’s such a great solution to, you know, having limited resources for one thing, for a lot of things involving citizens, but also for the folks who are involved, that probably provides a deeper sense of connection to the natural world for them and a greater sense of ownership, overlooking or looking, or what’s the word I’m looking for, stewardship for that particular area. So it’s, it’s great idea.

Mark Vukovich 41:15

Yeah, I you know Dean, I really modeled it. I don’t know if you know this. I modeled it after hawk watches. So there’s these prominent geographical places out there, and the most famous one is in Pennsylvania. It’s called Hawk Mountain, and I was an intern there. And it’s, it’s, it’s about hawks, though, and 1000s of visitors come there to watch the hawk migration over that, that that ridge, they fly right over your head at certain times of the year, and then eagles come later in the year. And that’s the model I it’s very it’s, it’s kind of similar to that, except it’s snakes, and it’s 2.6 miles, you know? It’s right, it’s a good it’s a little bit more of a workout versus a hawk watch where you’re, it’s basically a spot you’re, you’re just standing there and watching,

Dean Klinkenberg 42:11

Right. I guess that’s the other thing I forgot to mention. It’s two and a half miles one way, right? So if you walk, be prepared for a five mile round trip.

Mark Vukovich 42:21

Yeah, you’ll get your steps in. Yeah, that’d be good. You’ll get a little exercise, and it’s good. You know, people like that.

Dean Klinkenberg 42:27

You know, every, almost every time I’ve gone, I’ve stuck to the road itself, to the blacktop, but I noticed there are some trails kind of back through those areas. Could you just speak a little bit to the like the etiquette and what the expectations are for visitors, what’s what’s good stewardship and etiquette for visiting the area?

Mark Vukovich 42:47

Great question, Dean, thanks for asking. Yeah. I tell everybody, stick to the road, because that the place is unique. We want it there for future generations. A lot of those old trails were put in a long time ago, before the designation, some of them, and then just locals, just like, go off the road, and there’s no law against going off the road. But obviously during the snake season, it’s probably safe to stick to the road. And so the volunteer program, the community science program. We have, we, the we do have a role is that you, you’re standing on the road counting the snakes. Now you can see a snake off the road and use binoculars even and count it, count it, and put the coordinates in in the observation in the app. But yeah, we asked our volunteers, don’t, don’t leave the road, because it’s more of a realistic, you know, realistic observation of the road itself. There’s, there’s some old studies on Snake Road, and it’s unclear whether the observers were on the road or off the road along the cliffs, and, you know, they got, like, 1000s of snakes, you know, back in the day or whatever. And they’re more likely going off the road to get a lot that many snakes. Most of the public, especially the first time people that come out there, they expect to see the snakes on the road, and so they walk the road, and they stay the road. And it’s a really great place to get over your fear of snakes, because the number one snake there is the cottonmouth, and when you walk up to it, it opens up that mouth, and you’re, oh, so it’s, it’s, it’s a really great place to get over your fear of venomous snakes. And we have three there. We have the northern cottonmouth, the copperhead and the timber rattlesnake.

Dean Klinkenberg 44:54

Yeah, I guess it goes without saying. I feel like we shouldn’t even have to say these things out loud. But don’t try. To pet the snakes, right? Like, people still try to pet bison in Yellowstone, but so apparently we oh, yeah, all these things, keep your distance, yeah, and they are. They’re not aggressive, right? Like, if you get too close and push their boundaries, then they’re going to get they may get aggressive, but if you keep your distance and a respectful distance, they’re not coming for you.

Mark Vukovich 45:21

No, but some of them, I would say, can be aggressive if you you get too close. And yeah, just it’s, it’s remarkable. We haven’t had many issues there at all with the public interaction there. So, yeah, it, it’s interesting. It’s just a unique place to have, you know, public with some venomous snakes around. In the old days, you know, they, you know, they would bring snake hooks, and they would poke at the snakes. And it’s, it’s fun. It’s, it’s fun watching the evolution of of us, because we went from that to cameras, right, cell phones. And so, you know now, it’s about posting to social media like, oh, look at this snake, and getting 1000 likes. In the old days, it was about picking it up and maybe even killing the snake. You know, we’ve we’ve come a long way. So snakes used to be heavily persecuted, and now people are actually flying from Colorado Springs to see them and photograph them, spending 1000s of dollars.

Dean Klinkenberg 46:39

Fantastic. It wasn’t that long ago there was a bounty on rattlesnakes in our area.

Mark Vukovich 46:45

Oh yeah, oh yeah. And see, that’s why it’s very similar to Hawk Mountain, because in Pennsylvania there was a bounty on Cooper’s hawks. And believe it or not, bald eagles. They used to shoot bald eagles all the time. You know, if you, if you go back and tell them Alaska, Alaska was the only state that was exempt from the at that time, it was called the bald, bald eagle act. They added the golden eagle later. But Alaska was exempt because, you know, when they, you know, they bald eagles were eating all the fish, right.

Dean Klinkenberg 47:21

Right. Well, you mentioned earlier that birds are really your your first love, your passion, and I know you’re involved in some forest management programs within the Forest Service there at Shawnee, probably much of that is aimed at maintaining bird habitat then, or tell me a little bit about the forest management that you management that you’re involved with.

Mark Vukovich 47:22

Great, great question. So basically, all our forest management is tied to wildlife management. We’re we’re doing forest manage, management for wildlife and to improve the habitat for wildlife. And that is another really. So my number one task here is federally endangered species, and that’s mostly bats, and we could talk about that later or not. But I’m also there to track our management and see the benefits of our management and and how to improve the management if it’s not benefiting. And so and birds are the easiest, easiest animal to do that, because they’re highly visible. They’re songsters and and they react quickly to habitat changes and and it’s cheap. I go in, I do bird surveys. I just have data sheets and a pencil and some gas for my my vehicle, and I get out there and I I do the survey 10 minute point counts, and then I enter all the data in a computer. And then you can see the the wildlife trends and and you can see. So what I typically do Dean is before we do a harvest of trees, and when we do harvest trees, we’re not taking all the trees, we’re leaving trees behind, a lot of trees behind. And we actually have, we actually measure that, and have trees per acre before, and trees per acre after, and other measurements like basal area, and things like that. So and what I do is I do bird surveys before the harvest and then after the harvest, and you can see some species are immediately showing up after our harvest, like redhead woodpecker in our pine areas are showing up immediately, because they like those park like conditions where the trees are a little bit more spread out and they’re all over it, and they react immediately. Mourning doves, which is a game species, show up immediately as well. And one of our goals with thinning the pines. I call it thinning, and that’s when we just kind of take some of the pines out, is to get to convert the area back to what it should be, because a lot of our pines are planted that we have 1000s of acres of planted pines here that should not be there. Now, LaRue-Pine Hills was one of the only areas that had native short leaf pine. But that’s about it. All these other counties, like Pope County, especially, pines weren’t really known to be there at all, and so they’re we call them planted pines. And when we thin this out, we want the hardwoods to come back, and those seeds are in the in the soil. Oak and hickory are. They’re in the soil waiting to come back, like we want to come back. And when they start to come back, then we get blue-winged warblers. And I’ve seen that blue-winged warblers are, they like that early successional stage of oak and hickory and and trees like a shrubland, and there are another species that react pretty quickly, yellow breasted chat and prairie warblers are others. So it’s fun seeing that. Then we have, we have some really interesting, unique birds that kind of react to the pines, and that’s red crossbills. We just learned that last couple years, like we had the first red crosbill nest in Illinois in one of these areas of harvested pines. So it I love my job. I’m learning. I’m always learning things, and it’s also my job to communicate this to the public. And that’s why I was I was happy to join you today.

Dean Klinkenberg 48:57

Yeah, it’s fascinating to me too. I wrote a natural history guide for the Mississippi Valley that just came out in May. And one of the things I loved about doing that is it really opened my eyes to how many, how diverse these ecosystems can be, like we think of for and I’ll speak for myself, you know, I thought of forests as fairly homogenous, but they’re not like there’s so many different kinds of forest communities, different kinds of trees. So can you just kind of give us an overview of historically, like, what kinds of forest communities would have been down on that part of Illinois where the Shawnee Forest is today?

Mark Vukovich 52:32

Yeah, excellent question. So yeah, in the past, it was mostly, is this region is called the central hardwoods. It was mostly hardwood species with very few areas of of native pines, Larue-Pine Hills, maybe a few other areas. But overall, the composition was like over 90% hardwood. And then obviously, this is the northern extent of cypress, bald cypress as well, just to the south, though not, not so far north. And a lot of that was cut over, especially after the big Chicago Fire. And so that was the composition. And then swamps you had, you had bottom land, swamp, swampy areas, and then you have dry-mesic hill, hillsides and uplands with different species as well, and then riparian areas with different species. And that’s typically the model here. And then a lot of that was converted and cut over and bulldozed into farmland, and with severe erosion issues, they brought in loblolly pine and short leaf quickly to stabilize the soil. And so a lot of what we see now is not really the historical forest that it was, and we’re trying to convert it back very slowly. We’re only managing like our pines is less less than 1%. We have managed pines, it’s less than 1%, so we’re barely making a footprint with our management, but we’re seeing amazing results in those areas, and we’re just getting started, because we had a 17 year injunction on us, and our our server culture shop is just getting started back up, and we have, we have hopeful plans for the future to get things going, because I’m of the management side, and I see a lot of benefits with it. And when we have an aging forest like we do now, and it’s over overstocked, and the basal area and stem density of the trees is too close together. Um. It’s, it’s not, it’s not beneficial for all species. It’s beneficial to a one community species and the forest service we’re managing for biodiversity here and having different habitats like you said. Even though some of the habitats shouldn’t really be here, like the planted pines, a lot of bird watchers still like it. You know, they’ll, they, they enjoy it, and hunters, they’ll still use it. But it’s really not supposed to be here. And we’re going to slow. They’re going to be here forever, because we, we can’t manage everything very quickly here. And so it’s going to be a situation that we’re going to be we’re going to have for for decades and decades, the pines, the planted pines, will always be here.

Dean Klinkenberg 55:46

Right. There’s so many of them, they’re not going away anytime, right? So when you walk into a forest community, can you kind of…can you get a pretty good idea of what birds might be around based on the kinds of trees you see?

Mark Vukovich 56:00

Oh yeah, absolutely. Now, you know, I’ve been here five years, and that was one of the first things I did as I, you know, I wanted to get a command of what we had here, because I haven’t lived here in the Midwest. And, yeah, now I’m really confident, basically looking at a map, really, and if you if the Forest Service survey that area, I’ll know what tree species are there, and I’ll have a good idea what’s there. The one species of bird that is really interesting and unique here is the cerulean warbler. And we, we have surveyed for those, I’ve surveyed with a really excellent IDNR (editor note: Illinois Department of Natural Resources) biologist, probably the best bird guy they have here in Southern Illinois. And we surveyed and looked for these really beautiful blue warblers, and we have mapped them out for the most part, some of the biggest areas, and those are in Jackson County, and they’re really confined to specific areas, and it’s, it’s really interesting. I don’t, we don’t really understand why, but it has to do with floodplain in riparian areas. And so it’s probably very much linked to tree species and insects for the most part. But no research has been done here, but it’s one more thing that we’ve done recently that I think is is been beneficial for us as biologists and and to the birding community and the ornithological community, because nobody has really mapped out this population yet fully.

Dean Klinkenberg 57:48

So now that we’re kind of heading toward fall, even if it doesn’t feel like it, today is recording, it still feels like summer around here. What can people expect to see for bird populations down in that area around LaRue-Pine Hills, as we get into the fall.

Mark Vukovich 58:06

Okay. Well, it’s fall migration, that’s for sure. And we get a lot of bird watchers that come to Snake Road they’re looking up and not down. It’s kind of, can be kind of a dangerous situation, if you think about it. But this time of year we get the confusing fall warblers where they’re malting, and a lot of them do not they’re not in their breeding plumage. And you better get a good field guide to kind of show you what species look like in their fall plumage, because you can get pretty confused quickly. But you get here, one of the reasons why I moved up here is we’re in the flyway. We’re, you know, right along the Mississippi River is an excellent place. And so you’ll get golden-winged warblers, blue-winged warblers migrating, if you’re really lucky, a black-throated blue warbler, which is rare. Black-throated greens are very common in the fall here, scarlet tanagers, which isn’t warbler, but it’s a great time. The bird migration here is just absolutely fantastic. But if you talk to a lot of birders and beginners, fall is pretty tough because of the confusing plumages that the warblers have. Spring is probably, I like the spring better because the males are coming back in their in their bright breeding plumage. They’re singing, you know, this time of year, in the fall, they don’t they don’t sing unless the weather is just right. They might blurt out half a song. They just typically do some calls. So it’s a little bit more difficult in the fall, but it’s, it’s still really good, and it’s challenging. And if you you like a challenge like me, you’ll still you’ll still do it, you’ll still go at you’ll still watch and try to get as many as you can.

Dean Klinkenberg 1:00:00

Yeah, yeah. So probably waterfowl would be easier to spot, and you probably, does that area…you mentioned duck hunters, that was a historical area for duck hunting. So what kinds of waterfowl will be coming through this fall in that particular area around Larue-Pine Hills?

Mark Vukovich 1:00:17

Oh, yeah, right now wood ducks and blue wing teal are coming through. Those are the big ones later on, the bigger ducks, like mallards. Yeah, it’s, it’s a pretty popular duck hole, but a lot of lot of the private land now have kind of figured it out, and they’ll, you know, farmers will lease out their land and and and leave some corn, and then flood these areas that have corn, and they’ll lease it out to duck hunters and duck hunters who use that as well. So you see a lot of competition on private land and but you still have these, the local contingent that love LaRue for duck hunting.

Dean Klinkenberg 1:01:05

So do you do you have your own, like, favorite spot somewhere in Shawnee Forest? That’s part of your routine. You don’t have to share the exact location, but, like, if you don’t want to, but is there? Do you have maybe one or two favorite spots that you really enjoy?

Mark Vukovich 1:01:21

Well, if you go to so I put some, I put a lot of my observations in eBird, which is a citizen science app. If you were you could spy on me and go to eBird and look me up, I guess, and see where I go. But I do hang out at LaRue a lot during during the snake closure, if I can. But I really like our management, our areas that are completed, that that we’ve that we’ve finished harvesting trees, because all these species have come in that aren’t typically in our unmanaged areas, like redhead woodpeckers, red crossbills, blue-winged warblers, those, those are my favorite areas. Is where management has occurred, and that’s in Pope County. Unfortunately, this is, this is the unfortunate part of it. It’s in Pope County and Hardin County out in middle of nowhere. So after that, I would say LaRue and Oakwood Bottoms is a very popular bird place, because, you know, once again, it’s right along the Mississippi River. We flood it and we get wading birds there. And ahingas have been seen there. Mississippi kites nest there in the summer. It’s an excellent spot, but LaRue is really LaRue has, like, everything it has. It’s really good bird migration and, oh, don’t watch where you’re stepping, because you’re going to trip over snake. And then if you’re bored with that, then just look at all the plants. And it really just has, has everything you need. And if you really want a nice scenery shot, get on Pine Hills Road up on top and take a, you know, on a pull off and take a shot of of the whole little valley there, flood plain valley from on top of the rocks up there. Go to Inspiration Point.

Dean Klinkenberg 1:03:20

Inspiration Point’s got a great view from up there.

Mark Vukovich 1:03:22

Yeah, yeah. That place isn’t for everybody, though it’s yeah, we it can be dangerous. You got to be careful there.

Dean Klinkenberg 1:03:31

And it’s always windier up there.

Mark Vukovich 1:03:34

Yeah, yeah. But it’s very popular.

Dean Klinkenberg 1:03:38

Fantastic, yeah. Let me ask you this quick question, like a practical thing. I am a big fan of birds, too, but I’m partially colorblind. I don’t think I would ever be very good at visually identifying different species, especially if they’re distinguished mostly by colors, but I’ve been using Merlin by songs like, what’s your take on Merlin? Is it reasonably accurate?

Mark Vukovich 1:04:03

Well, no, it’s not 100% accurate. I think it’s been, I think it’s been a positive thing, because it can get people interested in in birds. And my my other biologist, she uses it to help her point her in the right direction, and it engages. This is what is really good about it. It engages people and figuring out what it is. So when I first started, Dean, back in the 90s, at Asheville UNCA, all we had were those CDs. You know, this was like, you know, before cell phones for the most part. And so I had to figure out, you know, I joke around with some of these young kids, this young biologist, I’m like, you guys have it easy here with all these gadgets. You know, back in the old days, we had to go back to the CDs, and then on the rare bird reports, you had to call, and it went to an answering machine, and you had to listen to the whole anwering machine and write it all down. Then you have to call back, because you didn’t get it all. Now, with eBird, you get the coordinates of that rare bird and the time of the sighting and a photograph so you it’s verified, and you can go right to it. You just navigate right to it. So it’s, it’s a it is a great time to be alive with all this technology like Merlin to help you navigate the natural world and learn about it and interact with it. Merlin isn’t the only thing. Like there’s other apps by naturalists that will basically take a picture and kind of tell you what it is, more times than not, you know it’s it could be wrong depending on what it is, but it’s right. I mean, I’ve used it and it’s, it’s, it’s right a lot too.

Dean Klinkenberg 1:05:48

I appreciate the apps. I think mostly just it helped me appreciate the diversity of species. In particular, I usually have my cell phone with me when I can’t, but one of my favorite things to do when I wake up in the morning is to open the Merlin app. Birds are more active in the morning, typically. And I’ll open up Merlin and let it listen, just to get a sense of how many different birds or species might be around me. And there have been mornings been it’s identified 10 or 12 different species. And I’m sure there’s, you know, there’s some error in what it’s picking up, but even if it’s only eight different species or whatever, I find that fascinating, that there’s that much variety going on around me.

Mark Vukovich 1:06:32

Yeah, and I’m old time biologist. I’m 50, I worry about being replaced by machine. Really do, because I came up in the field before the machines, you know, I, I’ve, I’ve deployed some of these ARUs,automatic recording units, up in trees to record birds, and it and it stores the data, and then you put it in a computer, and it’ll analyze and tell you what what you have. But some of that is wrong, because you have to train the computer how to identify the sounds. But, yeah, I really worry about that being replaced. And I like to pride. I pride myself in trying to be better than the machine, you know, but I’m as I get older, it’s it’s getting harder. I lose my hearing. I can’t imagine losing my hearing. As for color blindness, Dean, I have been out with bird watchers that have that, and they can still ID the bird by the silhouette of the bird, just by the what it looks like the silhouette. They can pretty much narrow it down. I’ve been out some some really interesting people all walks of life. You know firefighters. I met firefighters that are phenomenal birders. You don’t have to be a biologist to be an excellent bird watcher. I’ve, I’ve seen it. I know some that are just, they just do it as a hobby. And they’re, they’re better. They’re better than some wildlife biologists, I know that don’t even do birds like, yeah, I’m not, you know, they’re a wildlife biologist, but they’re doing deer and big game species. They don’t, they don’t really care about the birds so much, or they care about they just don’t know how to do it.

Dean Klinkenberg 1:08:16

Right. I don’t think the apps are going to replace you anytime soon. I think you’re any danger there. I think probably, if anything, it helps to amplify what you’re what you’re already doing, like as you’ve said. You can’t be everywhere at once, as it is. Yes, so if those apps help, it’s a good tool, yeah. And if it helps people connect to and understand more about the world around them, that’s a good thing in the bigger picture. I think.

Mark Vukovich 1:08:40

Oh, yeah, I totally agree.

Dean Klinkenberg 1:08:43

Well, I promised you, you know, half hour, 45 minutes, and we’ve blown past that, as I always seem to do. So let’s kind of wrap this up. If people are interested in finding out more about let’s start with Snake Road and maybe Shawnee Forest in general. What are the great places, or the best places that people could go to learn more?

Mark Vukovich 1:09:03

Well, the Shawnee National Forest website. And then we have a really excellent like front desk, people at at Vienna, Hidden Springs Ranger district in Vienna. And then our office here in Jonesboro, the Mississippi Bluffs are our front person. Our front office persons are really informative. And if they don’t know, they ask us, the specialists, wildlifeologists and others, where to go. But our website’s good. And then Illinois Extension, you know, U of I Extension. They have a lot of really good and they’re a partner of ours. They have a lot of good information on their websites. You can Google them and and Google the subject that you’re interested in and, and obviously, we have a lot of different areas that you and I didn’t discuss. We. Kind of we’re focusing on LaRue, but Garden of the Gods is probably our most popular site. So we get a lot of visitation there, and then a lot of our wilderness areas. We have seven wilderness areas. Lush Creek, I think, is probably one of our more popular ones, but Clear Creek and Bald Knob are right next to LaRue, and that’s fairly it’s kind of kind of long arduous hiking in there because of how steep it is, but it’s, it’s really good area. And then the Little Grand Canyon, which is a little bit further north, that’s a really good area to visit as well, but it’s arduous as well, heights up and down a giant hill.

Dean Klinkenberg 1:10:47

There’s just so many beautiful, spectacular sites in Southern Illinois, and I’m still trying to get familiar with a lot of that, and I feel like I’ve been spending a lot of the last three or four years going down there and visiting new places. But there’s, there’s a lot to see and do down there. And I really think that, you know, the area around LaRue-Pine Hills, like, even if you don’t see a snake, even if you don’t go, you know, during the closure, the road closures, I just think that’s a beautiful spot in general that people would probably enjoy spending some time in.

Mark Vukovich 1:11:18

Yeah, I think, personally, I think it’s our second most visited place, but we have some really popular campgrounds, and so I can’t really say that, but yeah, I think it’s up there. It’s definitely in the top five. And you’re absolutely right about Southern Illinois. The bird migration here is great. Duck hunting is great if you’re a wildlife enthusiast or a biologist or even a botanist. This is the place to be. You get northern species, southern species, eastern and western. I’m a deer hunter. The deer hunting here is fantastic. I love it. Yeah, it’s got everything I need. It’s a fun place. There’s plenty to do.

Dean Klinkenberg 1:11:59

Well, Mark, thank you so much for your time. I really appreciate this. This was fantastic.

Mark Vukovich 1:12:04

Alright, yeah, thank you, Dean. I enjoyed it.

Dean Klinkenberg 1:12:08

Thanks for listening. If you enjoyed this episode, subscribe to the series on your favorite podcast app so you don’t miss out on future episodes. I offer the podcast for free, but when you support the show with a few bucks through Patreon to help keep the program going. Just go to patreon.com/deanklinkenberg. If you want to know more about the Mississippi River, check out my books. I write the Mississippi Valley Traveler guide books for people who want to get to know the Mississippi better. I also write the Frank Dodge mystery series that’s set in places along the river. Find them wherever books are sold. The Mississippi Valley Traveler podcast is written and produced by me, Dean Klinkenberg. Original Music by Noah Fence. See you next time you