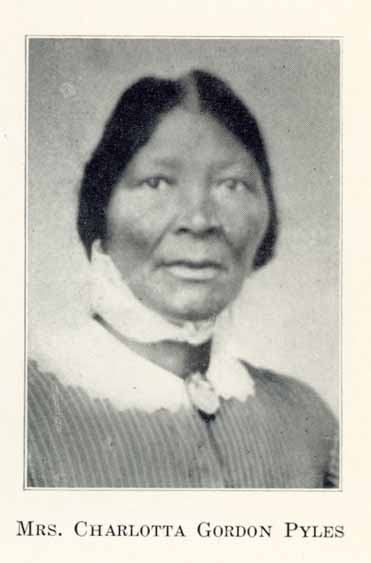

In this week’s episode, we uncover the surprising story of Iowa’s pivotal role in African American civil rights. From the groundbreaking 1839 court case that made Iowa a free territory to the remarkable story of Charlotta Pyles—a formerly enslaved woman who raised $3,000 through East Coast speaking tours to free her family members—we explore how this Midwestern state led the nation in civil rights advances.

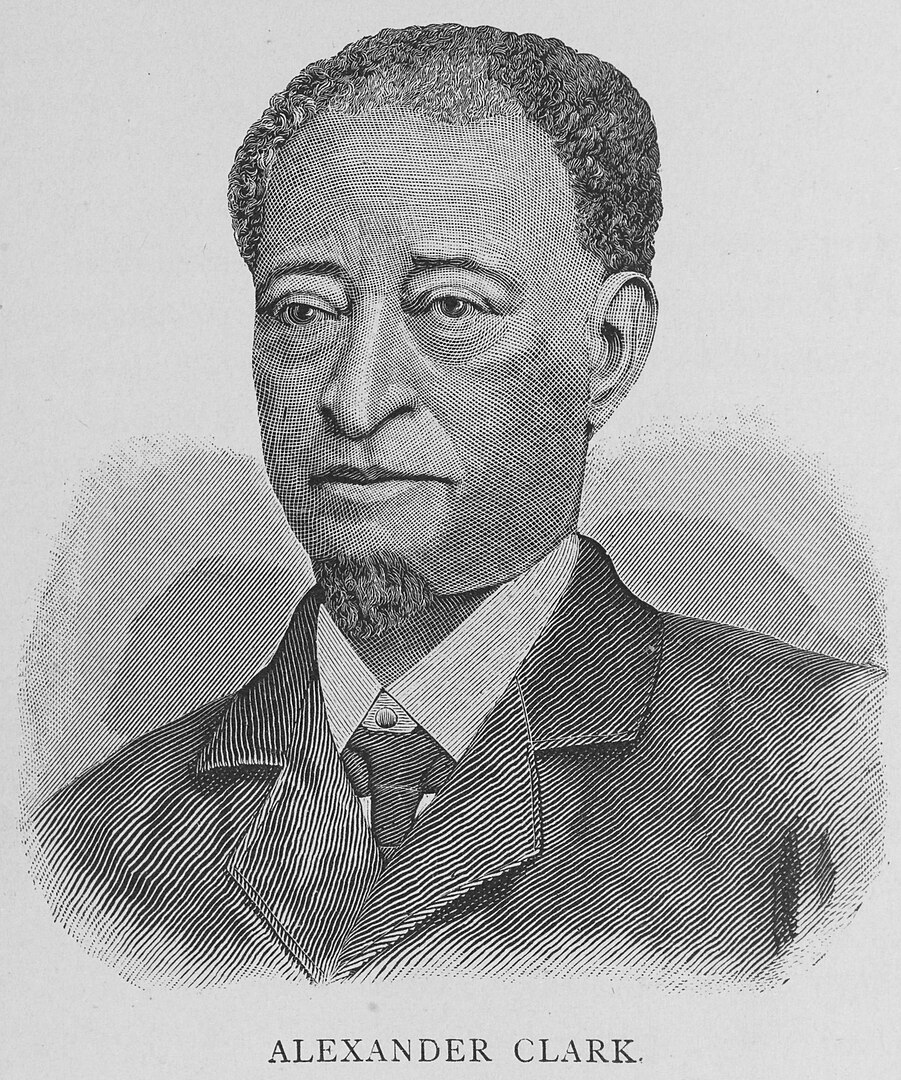

Learn about Alexander Clark, a self-made businessman who successfully fought to desegregate Iowa’s schools nearly 90 years before Brown v. Board of Education, and hear the inspiring tale of the Pyles family’s daring escape from Kentucky to freedom in Keokuk.

Show Notes

Support the Show

If you are enjoying the podcast, please consider showing your support by making a one-time contribution or by supporting as a regular contributor through Patreon. Every dollar you contribute makes it possible for me to continue sharing stories about America’s Greatest River.

Don’t want to deal with Patreon? No worries. You can show some love by buying me a coffee (which I drink a lot of!). Just click on the link below.

Transcript

Fri, Feb 07, 2025 9:43AM • 25:22

SUMMARY KEYWORDS

Civil rights, Iowa, Mississippi River, Alexander Clark, Charlotta Pyles, Underground Railroad, African Americans, Muscatine, Burlington, Keokuk, Slavery, Iowa Supreme Court, Segregation, Education, Civil War.

SPEAKERS

Dean Klinkenberg

Dean Klinkenberg 00:00

In July 1839, the territorial Supreme Court ruled that Ralph did indeed owe Montgomery the money specified in their contract. But that “no man in this territory can be reduced to slavery.” Welcome to the Mississippi Valley Traveler Podcast. I’m Dean Klinkenberg, and I’ve been exploring the deep history and rich culture of the people and places along America’s greatest river, the Mississippi, since 2007. Join me as I go deep into the characters and places along the river, and occasionally wander into other stories from the Midwest and other rivers. Read the episode show notes and get more information on the Mississippi at MississippiValleyTraveler.com. Let’s get going. Welcome to Episode 56 of the Mississippi Valley Traveler podcast. Well, as we slide into February 2025 I was thinking about the stories of a few civil rights pioneers who most people probably have never heard of. So in this episode, we’re going to take a look at Iowa. We’re going to visit Iowa in the early 19th century, and I’m going to tell you stories about a few of the people who helped pave the way for major civil rights victories that really reshaped the lives of African Americans in the state. We don’t really think of Iowa when we think about civil rights landmarks, but maybe after this episode, you will. So I’ve got stories from the major cities in southeast Iowa, from Muscatine, Burlington and Keokuk, and a few of the people who left a lasting impact. You’ll hear about Alexander Clark and Charlotta Pyles in particular, as well as a couple of other folks in the show notes. I’ll post a couple of links for further reading, and I may have a picture or two that I’ll post there as well. That’s at Mississippi ValleyTraveler.com/podcast. Thanks to those of you who continue to show me some love through Patreon. I appreciate your ongoing support. You really make this podcast viable. If you want to join the Patreon community for as little as $1 a month, you can join that community and get early access to these episodes. Go to patreon.com/DeanKlinkenberg, and you can join the community there. Don’t feel like joining Patreon, well, you can buy me a coffee. I’m a regular coffee drinker, and I appreciate every help supporting that habit. Want to know how to do that? Go to MississippiValleyTraveler.com/podcast, and there you’ll find instructions on how to buy me a coffee. And now let’s get on with the episode. When we think about places that have marked important civil rights milestones, most of us probably don’t think about Iowa. We should. Iowa may have a relatively small African American population today, about 4% of the state’s 3 million residents, but at one time, the state has been ahead of the curve for guaranteeing equal rights to all citizens. It hasn’t come easy, though. The US Congress created the Iowa territory in 1838, after the Black Hawk War that forced the Meskwawki and Sauk people to cede their land. The Territorial legislature passed a law forbidding black men from living in the state unless they showed papers proving they were free and they could post a bond of $500. Still, the new territory proved more hospitable in other ways. The very first case decided by the Iowa Supreme Court, then the Territorial Supreme Court involved the status of an enslaved man named Ralph. He and his enslaver, a man from Missouri, known as Montgomery, had signed a written contract giving Ralph permission to move to Iowa and earn wages to buy his freedom. If Ralph could earn enough money to pay Montgomery 550 bucks plus interest, Ralph would be a free man. Ralph moved to Dubuque and found work in the lead mines. Five years passed though, and Ralph hadn’t sent any money back to his enslaver in Missouri, so Montgomery hired bounty hunters to bring Ralph back to Missouri in slavery. The bounty hunters found Ralph and took him to district court to secure legal permission to return him. The district court transferred the case to the Supreme Court. In July 1839, the Territorial Supreme Court ruled that Ralph did indeed owe Montgomery the money specified in their contract. But that, “no man in this territory can be reduced to slavery.” The Court declared that when Montgomery allowed Ralph to move and live in free territory. Montgomery lost all rights to control him. Slavery was therefore illegal in the territory, and formerly enslaved blacks living in the territory were also free when Iowa entered the United States on December 28, 1846. It did so as a free state. More African Americans followed the same path as Ralph and moved to Dubuque to work in the lead mines. Others settled in river towns, Muscatine, Burlington, Keokuk, especially where they found work as roustabouts and deckhands. Still, while white Iowans generally opposed slavery, and some helped enslave blacks to their freedom through the Underground Railroad, most white Iowans, like most white Americans at the time, did not view African Americans as their equals. In 1851 for example, the state legislature barred blacks from voting or holding seats in the legislature in early Iowa, like in many states, blacks could not marry whites, could not serve in the militia and could not testify in court against a white person. Black Iowans would again have to take to the courts to live as free people with the same rights and responsibilities as white Iowans. That early case wasn’t the only one where an Iowa court equalized the rights of black citizens in the state. Alexander Clark moved to Muscatine at age 16. He was born a free man in Pennsylvania to parents who had been freed from enslavement. When he was 13, he moved to Cincinnati, where he lived with an uncle who taught him how to be a barber. He later found work on a steamboat, and at age 16, put down roots in Muscatine, which was then known as Bloomington. Clark had an entrepreneurial spirit. He set up a business as a barber, sold cord wood to passing steamboats, and also sold real estate. In 1848 he married Katherine Griffin, who was born enslaved, but had been freed at age three. They had five children, but two of them died as infants. Muscatine black population grew steadily before the Civil War, as formerly enslaved people and free blacks from the east made the city home. Jim White was one of the new black residents. His enslaver had moved from St Louis to a farm north of Muscatine, and Jim wasn’t crazy about farm life, so he left the farm and got a job working at a hotel in Muscatine. His enslaver wasn’t too keen on this, so he sent an officer from St Louis to take him back south. When the officer tried to arrest Jim at the hotel where Jim worked, the proprietor intervened, Alexander Clark, gave Jim shelter as his case went before the justice of the peace to determine if the officer had the legal right, the legal standing to apprehend him. After a boisterous three day hearing where the courtroom resounded with quotes from the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, the judge sided with Jim. This event triggered some pro slavery advocates to call Muscatine an abolitionist hell. Jim, by the way, survived a couple more attempts to kidnap him and take him back to St Louis. Ultimately, the Iowa Supreme Court ruled in his favor, although just on a legal technicality, Jim lived out the rest of his life as a free man in Muscatine. Alexander Clark continued his consequential life in Muscatine. He was a founding member of the Muscatine African Methodist Episcopal Church, and during the Civil War, helped recruit black soldiers in Iowa to join the Union Army. After the Civil War, Muscatine still enforced segregation in its schools in 1867 he tried to enroll his 12 year old daughter in the white secondary school. There was no secondary school for blacks, but she was turned away. So he sued the Muscatine Board of Education and won. In 1868, the same year black men won the right to vote in Iowa. The Iowa Supreme Court justices asserted that nothing in the Iowa constitution permitted racially segregating public schools. Within a few years, all of Iowa schools were desegregated nearly 90 years before Brown versus Board of Education did the same thing for the rest of the country. Clark’s story didn’t end there. His son Alexander Jr, graduated from the University of Iowa Law School in 1879. The first African American to do so. Alexander senior himself became the second black graduate of the Law School five years later. In 1890 President Benjamin Harrison appointed Alexander Clark senior ambassador to Liberia. He didn’t get to enjoy the post long however. The following year, he died in Liberia. He’s buried in Muscatine Greenwood Cemetery. Many of the early white residents of southeast Iowa embraced pro slave reviews, partly because of trading relationships along the Mississippi with slave holding states, and partly because many had roots in the South. For example, when news trickled up river that a mob had killed abolitionist Elijah Lovejoy at Alton, Illinois in 1837 a cheer erupted from a crowd on the Burlington riverfront. Meanwhile, Burlington Congregational Church used a vaulted brick room to shelter escaped enslaved blacks working their way along the under underground railroad. The church’s pastor, William Salter, also hid people in his barn who were escaping enslavement. While Burlington had black residents nearly from the city’s founding, black migration to the city jumped after the Civil War. By 1875, 300 African Americans called the city home. The community grew larger between 1880 and 1920 when some coal and railroad companies brought African Americans from the South to work during strikes. Most black residents, though, worked in low status jobs and in industrial areas. The black population peaked in Burlington around 1920 then declined during the depression before picking up again after World War II. The city’s social life remained mostly segregated. However, while white residents contributed money to help build some of the city’s African American churches, black and white movie patrons sat in separate sections, and swimming pools and bowling alleys were also segregated. Many hotels wouldn’t serve black customers. Still, black residents of Burlington have left their mark in many ways. Bessie Viola Johnson sang and wrote songs, including the acclaimed “Heart of the Middle West.” A formerly enslaved couple, Aunt kitty and Uncle Ben Sandridge paid for a bell to celebrate their journey to freedom. While they were enslaved in Kentucky, they asked a Burlington man, Mr. Wallace, to buy their freedom and take them to a free state, promising to pay him back. He agreed, remarkably, then took them to Burlington. Within three years, they had paid him back in full. When Aunt Kitty died in 1863 she left a bequest to purchase a bell, which he called her liberty bell. The bell was installed in 1865 and now rests in a cloister at Parkside First Baptist Church. Hey, Dean Klinkenberg here, interrupting myself. Just wanted to remind you that if you’d like to know more about the Mississippi River, check out my books. I write the Mississippi Valley Traveler guide books for people who want to get to know the Mississippi better. I also write the Frank Dodge mystery series that is set in places along the Mississippi. My newest book, The Wild Mississippi, goes deep into the world of Old Man River. Learn about the varied and complex ecosystem supported by the Mississippi, the plant and animal life that depends on them. And where you can go to experience it all. Find any of these wherever books are sold. In 1873 Emma Coger, a biracial resident of Quincy, Illinois, was traveling back home after boarding a steamboat in Keokuk. She’d bought a ticket that gave her a seat at the first class dining table, but the captain had her removed because the North Western Union Packet Company had a policy that banned blacks from the first class dining. She sued and won. The Iowa Supreme Court determined that she was entitled to the same rights and privileges as white passengers. It would be another 90 years before the US Supreme Court determined that black Americans were entitled to the same rights and privileges in public accommodations as white Americans. Keokuk was built about 90 miles north of Hannibal, Missouri, a place where the Mississippi floodplain is bisected by a five mile wide valley carved by the Des Moines River. Missouri is south of the river. Iowa is north. It’s a scenic area, but not especially remarkable. The Missouri side today has a fireworks super store, while the Iowa side has well, mostly fields of corn. Before the Civil War, though, crossing the river was a big deal, especially if you were black, because the Des Moines River marked the boundary between freedom and slavery at the confluence of the two rivers on the free side of the border. The city of Keokuk was built on high bluff above the rivers, perhaps because of its location as the first free city on the west bank of the Mississippi. Keokuk attracted a significant number of black residents before the Civil War, a community that grew through the 19th century after the Civil War, many blacks, mostly formerly enslaved folks, were on the move, looking for new opportunities away from their former enslavers. Some traveled up the Mississippi River and settled in river towns, at least for a while, for the most part, though, those early black migrants were making a pit stop on the way further west. Not in Keokuk, though, where a significant number stayed and built a community. Charlotta Gordon Pyles was among the first African Americans to settle in Keokuk. Charlotta and her 12 children were enslaved by Hugh and Sarah Gordon of Bardstown, Kentucky. When Hugh died in 1834 he left Charlotta and some of her children to his only daughter, Frances, with the expectation that she would give them their freedom. Charlotta was married to Harry Pyles as much as any enslaved person could be married anyway. Harry was a free man, but had no power to prevent his wife and children from being sold to another enslaver under the laws of the day. The children’s legal status was the same as the mothers. So Charlotta’s children were also enslaved, in spite of the unambiguous wishes of their father, Frances Gordon. Siblings were not of the same mind about freeing the Pyles family. In 1853 Frances’ brothers, William and the Reverend Joel Gordon, a Baptist minister, kidnapped one of Charlotta’s sons, Benjamin, and took him to Mississippi, where they sold him to William P Moore, who then took Benjamin to Missouri to work in his hemp fields. Her brother’s actions convinced Frances that she would have to leave Kentucky and head north in order to free Charlotta and her children. When the brothers learned of her plans, Joel sued Frances, claiming that she was no longer competent to manage her own affairs. Frances stood firm, though, and argued into Kentucky court that as a slave owner, she was allowed to move her slaves wherever she pleased. She won the case. A month after losing their suit, brothers Joe and William and a few other relatives sued Frances again. This time, the sheriff arrested the Pyles family and hauled them to jail on a rainy fall night. Frances followed them, but it took her two days to get them all released. The sheriff also handed her a bill for $51.35 for the cost of jailing them. The case against Frances was thrown out in March 1854, but she and the Pyles family were long gone by then. They left Kentucky shortly after the Pyles family was released from jail. Frances was afraid her brothers might try to kidnap other members of the Pyles family, so she loaded all of them, Harry, Charlotta and 11 of her 12 kids and five grandchildren and all of their supplies, into a prairie schooner. Frances was 80 years old at the time they began to their escape. They traveled to Louisville, across the hills of Central Kentucky, then boarded a steamboat and traveled up the Ohio River to Cincinnati to meet the Reverend Claycomb, a friend who had agreed to accompany the group and route to Minnesota at Cincinnati. Then they returned down river, then back up the Mississippi to St Louis. The route through Missouri, a slave state, was fraught and unfamiliar, so for a $100 fee, nearly $3,000 today, they hired Nat Stone a St Louis to guide them across the terrain after they were well on their way. Stone decided that his services were worth more than his initial quote, so he asked for another $50 in return. For the extra money, he promised he wouldn’t turn the family over to slave traders in Missouri. What a guy. By the time they crossed the Des Moines River into Iowa, winter was settling in, making travel even more difficult. They settled in Keokuk, which in 1853 had transitioned from a lawless frontier town to a growing Mississippi river port of 3000 residents. Two years after the Pyles family arrived, Orion Clemens and his brother, Samuel, sent a print shop in downtown Keokuk. Frances continued to live with the Pyles family and worship at the same church, the First Baptist Church, and the whole group struggled mightily as they tried to settle into their new home. Charlotta came up with a big plan to give the family a boost. Two sons in law were still enslaved in the South. If they could somehow find a way to reunite with them, they could work, and the family just might make it. Charlotta contacted their enslavers and learned that she could purchase their freedom for $1,500 each, an enormous amount of money at that time, and equivalent to roughly $60,000 today. Charlotta’s kidnapped son, Benjamin had somehow heard of his mother’s plan and wrote to her, asking that she purchase his freedom instead of one of the brothers in law. Charlotta faced a terrible choice. She would never have the money to free them all. Ultimately, she rode back to her son and turned him down. She needed the two sons in law out of slavery to help support their families as soon as possible, Benjamin was still single, and she thought he might have a chance to run away. Benjamin, understandably, was not pleased with the answer. Charlotta soon lost touch with him, and the family never heard from him again. Charlotta still had the daunting task of raising that $3,000 so she embarked on a speaking tour around the East Coast in churches, private homes and public halls like Independence Hall in Philadelphia. She preached about the evils of slavery. Along the way, she befriended Susan B. Anthony and Frederick Douglass, who delivered a speech in Keokuk at the Chatham Square Church, a few years later. Charlotta succeeded. In six months, she raised the $3,000 and bought freedom for her two sons in law, not bad for a woman with a limited education. Charlotta and Harry Pyles were finally legally married on April 2, 1857 in Keokuk, and with most of the family back together and their finances more stable, Charlotta offered her home as a shelter to enslave people escaping to Canada along the underground railroad. Although the family made a home in Keokuk, racial segregation was still the norm in the 19th century, and Keokuk was no exception. It was especially hard to find a good school for a black child. The first school for blacks in Keokuk was built in 1869 at 11th and Maine, but it was meant mostly for primary school aged children. When Charlotta’s daughter,Charlotta Smith, tried to enroll her son Geroid in the all white public high school, school officials refused to admit him. Charlotta and other black families filed a lawsuit against the school. In 1875 the Iowa Supreme Court reaffirmed their 1868 decision on school integration. School officials in Keokuk didn’t fight the decision and began enrolling black students in 1876. Geroid Smith, the son and grandson of formerly enslaved people was one of the first black students to graduate from the integrated high school when he was awarded his diploma in 1880. As important as these victories of the 19th century were they didn’t end race based discrimination and prejudice In Iowa, of course Dorms at state universities remained segregated until after World War II. No black teachers worked in Iowa public schools until 1947 when the Des Moines schools hired Harriet Curley. Black residents of Des Moines had to sue a local drug store for the right to eat that store’s ice cream. Nevertheless, 19th century black residents of Iowa worked hard and risked a lot in the fight for equal treatment under the law. Without their efforts, Iowa would not have been the first state in the US to integrate its public schools, and black residents would have continued to be treated as second class citizens in everyday life. Thanks for listening. If you enjoyed this episode, subscribe to the series on your favorite podcast app so you don’t miss out on future episodes. I offer the podcast for free, but when you support the show with a few bucks through Patreon to help keep the program going, just go to patreon.com/deanklinkenberg, If you want to know more about the Mississippi River, check out my books. I write the Mississippi Valley Traveler guide books for people who want to get to know the Mississippi better. I also write the Frank Dodge mystery series that’s set in places along the river. Find them wherever books are sold. The Mississippi Valley Traveler podcast is written and produced by me, Dean Klinkenberg. Original Music by Noah Fence. See you next time you.