In 1993, the Great Mississippi River Flood upended lives throughout the Midwest, although the greatest damage was in the Mississippi River floodplain from the Quad Cities south to around Cairo, Illinois. Thousands of people were forced into temporary shelters, and 52 people. In the aftermath of the flooding, President Clinton established a commission to review the events of the Great Flood and to make recommend policies that could reduce future damages from big floods. He appointed Gen. Gerry Galloway to head the commission, which, after its release, became known as the Galloway report.

In this episode of the Mississippi Valley Traveler podcast, I have a wide-changing conversation with Gen. Galloway to review how we’ve done in the past 30 years to prepare for floods and reduce damages from those inevitable periods of high water. Our conversation went long, so I’m splitting the interview into two parts. In part one, we talk about how flood policy has evolved since 1993 and get into some of the difficult issues were still facing, such as who is ultimately responsible for flood protection and dealing with the risks of high water, who should pay for it, the challenges of coordinating floodplain policies among federal, state, and local governments and how expectations of federal bailouts can complicate those policies; the newer problems we’re facing with intense rainfall events that flood urban areas like the recent flooding in Burlington, Vermont, and the complications and problems with the federal flood insurance program.

In the Mississippi Minute, I share a couple of my memories from the flooding around St. Louis in 1993, but mostly I want to hear from you. What are your stories from the Great Flood of 1993? Share your stories with me at MississippiValleyTraveler.com/contact, and I’ll choose a few to share on the next podcast.

Show Notes

Support the Show

If you are enjoying the podcast, please consider showing your support by making a one-time contribution or by supporting as a regular contributor through Patreon. Every dollar you contribute makes it possible for me to continue sharing stories about America’s Greatest River.

Don’t want to deal with Patreon? No worries. You can show some love by buying me a coffee (which I drink a lot of!). Just click on the link below.

Transcript

SUMMARY KEYWORDS

levee, flood, flooded, people, river, problem, floodplain, community, flooding, mississippi, risk, area, water, state, mississippi river, insurance, live, land, federal government, wetlands

SPEAKERS

General Gerry Galloway, Dean Klinkenberg

General Gerry Galloway 00:00

The Flood of ’93 I call the CNN flood because up until then we’ve had floods. Floods are part of the nation’s history. And it’s amazing to see people that have gone through them and survived but most of the country didn’t know about it. And in 1993, CNN was just getting started with their around the clock coverage. And people couldn’t believe that week after week, month after month, this area was flooded.

Dean Klinkenberg 01:18

Welcome to the Mississippi Valley Traveler Podcast. I’m Dean Klinkenberg. And I’ve been exploring the deep history and rich culture of the people and places along America’s greatest river, the Mississippi, since 2007. Join me as I go deep into the characters and places along the river and occasionally wander into other stories from the Midwest and other rivers. Read the episode show notes and get more information on the Mississippi at MississippiValleyTraveler.com. Let’s get going.

Dean Klinkenberg 01:18

Welcome to Episode 25 of the Mississippi Valley Traveler Podcast. Well, it’s hard for me to believe this but thirty years ago the Mississippi River put on quite a show and disrupted a lot of lives. It’s hard for me to believe it’s been thirty years. I lived in St. Louis at that time, and I have some very specific and vivid images of what happened during the flooding. During that Great Flood of 1993. And I figured hey, we had to do a couple of episodes reflecting back on thirty years since the big flood. What we’ve learned and then looking ahead a little bit about what maybe we can expect going forward. Let me just give you a quick recap of what happened in 1993. In case you had forgotten, thirty years ago a weather pattern that produced a lot of rain parked itself over the middle part of the country and it didn’t leave for weeks. The resulting steady rains produced damaging flash floods on small creeks and streams and a classic slow moving big river flood. Midwestern soils were saturated after a wet fall in 1992. So when those heavy rains fell again in spring, the rivers came up pretty fast. Ultimately, though, the great flood of 1993 was remarkable, not just for the volume of water that flowed down the Mississippi, and there was a lot of it, but also for the unprecedented amount of time that the river stayed high. People in river communities not only had to fight back that high water they did it for weeks on end. It was exhausting. Grafton, Illinois, for example, was above flood stage for all but eighteen days from early March until mid October. Some rivers flooded in early May and then receded back into their banks and by mid July high water in the Mississippi was bad enough that it had shut down hundreds of miles of the river to barge traffic and several bridges had closed when high water crept across access roads. Levees burst in the Mississippi River Valley, middle and upper Mississippi Valley as the river reclaimed its historic floodplain. Communities rallied to sandbag vulnerable areas. Sometimes successfully, sometimes not. St. Genevieve and Prairie du Rocher, two historic river towns that were founded before the American Revolution had a lot of anxious moments but ultimately fended off what could have been catastrophic damage. Ultimately, records were set along 1800 miles of Midwestern rivers, with another 1300 river miles experiencing levels close to record highs. Overall, almost seventy percent of the levees failed between the Quad Cities in Cairo, Illinois. Seventy percent. Most of the levees that gave way had been built and maintained by local interests to protect agricultural lands. But the Mississippi also reached 40 out of the 226 Federal levees. Nearly seven million acres flooded in 419 counties. Most of that again agricultural land. There was an estimate that about 100,000 homes were damaged from flooding all throughout the Midwest, and tens of thousands of people were forced into temporary shelters, sometimes for months. Total damages ended up being around $18 billion in 1993 dollars. And we know of 52 people who died as a direct result of the flooding. Iowa and Missouri were the hardest hit states but many other states in the Midwest suffered from flooding as well. I go into a lot more detail about this flood in my book, “Mississippi River Mayhem”. There’s a whole chapter on that. So if you’re wanting to know more. If you want to read some firsthand accounts from people who survived the flood, I suggest you pick up a copy of that book today. After the floodwaters had gone down, then President Clinton tapped General Gerry Galloway to lead a committee to review what happened in 1993 and make recommendations about what we can do going forward to prevent such extensive damage. The committee released the report in 1994. And that’s since become known colloquially as “The Galloway Report”. I’m pleased to tell you that the lead author of that report, General Galloway is my guest on the podcast this week. In fact, we had such a lengthy conversation that I feel like I need to split this into two episodes. So I’m going to do a part one today and a part two, in two weeks I’ll release with the rest of the interview. I think it’ll be easier to sort of digest and think about some of the topics that we get into. In this first part, we talk a little bit about how flood policy has evolved since 1993. And we get into some of the difficult issues we’re still facing, like, ‘who is ultimately responsible for flood protection and dealing with the risks of high water?’ ‘Who should pay for flood protection?’ The challenges of coordinating floodplain policies among federal, state and local governments and how expectations of federal bailouts can complicate those policies. The newer problems we’re facing today with intense rainfall events that are flooding urban areas like the recent flooding we saw in Burlington, Vermont, and the complications and problems with the Federal Flood Insurance Program. Let me know what you think. I hope you stick around for both parts of this. There’s a lot of meat to the interview a lot of great detail and reflection on the past thirty years and some thoughts on what we still need to do going forward. As usual, thanks to those of you who show me some love through Patreon. If you want to join that community, go to patreon.com/DeanKlinkenberg where you too can show some love. If Patreon isn’t your thing, hey, you can buy me a coffee. I have a steady caffeine habit, I would appreciate a little support for that, go to MississippiValleyTraveler.com/podcast to find out how you can support my caffeine habit. Now on with the interview. Here is General Gerry Galloway.

Dean Klinkenberg 07:10

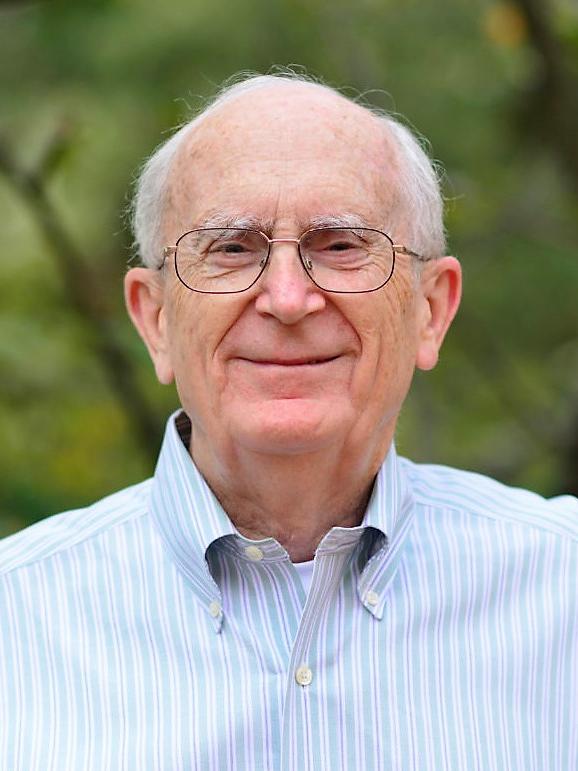

General Gerry Galloway Jr. is an Emeritus Research Professor of Engineering at the University of Maryland where his focus is on disaster resilience and mitigation, sustainable infrastructure development and national security. He joined the faculty of the University of Maryland following a thirty-eight year career in the US Army, retiring as Brigadier General, and served eight additional years in the federal government, most of which was associated with water resources management. He served for three years as District Engineer for the Army Corps in Vicksburg, Mississippi, and later for seven years as a presidential appointee to the Mississippi River Commission. He’s currently a member of the Board of Directors of the Water Institute of the Gulf, the Advisory Board of the Center for Climate and Security, and the CNA Military Advisory Board. In 1993, and ’94, he was assigned to the White House to lead an interagency study of the causes of the Great Mississippi River flood of 1993. And to make recommendations concerning the nation’s Floodplain Management Program, which is the reason we’re here to have this conversation today. So welcome to the podcast, General Galloway.

General Gerry Galloway 08:29

It’s my pleasure to be here and to be talking to somebody that knows where the Mississippi is and knows the challenges that existed in 1993 and 1994.

Dean Klinkenberg 08:40

I was living in St. Louis in ’93. I’ve been here for thirty-eight years or so. And I remember on that on the day that the flood crested at its height, I was downtown for a wedding. And I remember just sort of the general chaos in that moment. We had just had the levee breach in Chesterfield along the Missouri River that flooded the Chesterfield Valley. We’d have the levee breach in Illinois that probably spared us a foot or two in flood height along downtown St. Louis but flooded hundreds of square miles of Illinois. It was…it was a very memorable period of time and I’m also having a hard time accepting the fact that it’s been thirty years since all that happened.

General Gerry Galloway 09:19

Well, that’s for sure. The flood of ’93 I call the CNN flood because up until then, we’ve had floods floods are part of the nation’s history. And it’s amazing to see people that have gone through them and survived but most of the country didn’t know about it. And in 1993 CNN was just getting started with their around the clock coverage. And people couldn’t believe that week after week, month after month, this area was flooded, and people expect water to go right down. Have a flood a day or two, it’s gone. Here we are there were places in Illinois across the river from you that were underwater still, in October, it all went to the south and was draining solely for the few outlets we had into the Mississippi. So it certainly is something the nation should remember, on this 30th anniversary. And I think we’re learning more because we see more with the TV shows today. But but we also are experiencing more in many more places in the country, partially because we are putting ourselves at risk by building in the floodplain.

Dean Klinkenberg 10:33

Right. And that was one of the things I was hoping that we can have some conversation about today, too, is that I know I remember in that summer of ’93 I was out visiting some relatives in New York City who were very concerned about my well being, with the flooding going on in St. Louis. And it was, I guess, maybe our knowledge of geography isn’t always great, but they didn’t quite understand that it was a really a fairly narrow stretch of the Midwest that was affected directly by the Mississippi River floods. There were other areas that were flooded and upplands from other from heavier rains. But the along the Mississippi, it’s a fairly narrow range of the land that’s really that was underwater, and that was most affected by this. The floodplain – your report, you know, this kind of became known colloquially as “The Galloway Report”. Your your review that came out about a year later and the report focuses quite a bit on the issue of floodplain management. And I’m really curious now, like, with thirty years of hindsight, how have we done in the past thirty years with floodplain management? Are we better off now than we were in ’93?

General Gerry Galloway 11:39

Yes, for sure, we’re better off. More people understand it partly because of the education that takes place. When you have reports like that, and you have people then that carry on extensions of that report and try and solve some of the problems. And so we are better off in that sense. We’re not better off in the, in a manner that we are still struggling with very interesting political challenges. Getting people to control where people live, getting people to, on their own, understand the risk and do something about it. Our report said that the responsibility for the floods ran from the federal government to the state government to the local to the individual, his or her himself or herself, who was responsible for selecting the property. Not taking the right precautions when the floods have started to rise. Not moving out of the way. All of these sorts of things. And we still have those problems today. People are somewhat oblivious. The other thing we’ve discovered is that we can create problems for people that are downstream from us. And we still seem to have that problem. It’s interesting if we could go to Hurricane Harvey, which was really a rainstorm that caused the problem. Most of the problems in Houston itself were from people who had moved into the area to the west of Houston, and taken all of the land and forced all the water that came out of the sky, not to go into the ground and not to go into the storage areas, but to go downstream into the city of Houston. And again, we knew that development was taking place and we sort of “put our head in the sand” to watch it take place. And we see that all around the country. You know, the places in the St. Louis area where we took steps to move people out of the floodplain had been flooded since and nobody was hurt. But we are still building in St. Charles area where Chesterfield is packed tight. You don’t know how big this storm is going to be. And we learned that when you get fifty-six inches of rain in Beaumont, or you get the heavy rains I had yesterday in upstate New York and now is in Vermont, where in a few hours you have inches of rain that just cause the system not to be able to cope with it. So we’ve got a lot to remember and a lot to learn.

Dean Klinkenberg 14:07

What are the issues as you see it that are getting in the way of wise floodplain development?

General Gerry Galloway 14:18

Well, I think getting in the way of not slowing that floodplain development is the inability of local officials to stand up and say, “this is not a good idea”. I mean, it is in honesty, there are some that do that. The real estate lobby, bless them, is trying to get you a good house and me a good house. But on the other hand, they don’t want to have signs in front of the houses or the neighborhood that says this area flooded in 1993 or this area flooded two years ago. And our studies have shown that it doesn’t take more than a few years or even some cases a few months for people to want to move back into an area that was flooded and the politicians are not willing to step in and stop that. I want to say is one thing that came out of the Hurricane Harvey issue, we weren’t able to get out of the Mississippi Flood of ’93, was the state, in this case Texas, stood up and said, “we are going to make sure people know and understand that they’re at risk”. And they’re putting together a database that will allow you to look at your property, and it’s going to tell you everything that’s wrong with it, and that you’re at risk of flooding. And so you can’t say I didn’t know. And it would tell you that, if I’m going to buy it, you still may want to buy it but it’ll tell you that you better take some precautions in doing it. Don’t put your treasures on the first floor or worse than that in the basement.

Dean Klinkenberg 15:49

Right. And I guess that’s one of the things that I think about too, like some of these areas have been developed for a while some of the floodplains, and some places in some cases after ’93, like for Valmeyer, they moved most of the town out and up into into the bluffs to higher ground. And then we still have places that are looking at, as you alluded to new development in undeveloped floodplains, particularly around the Missouri River here in the St. Louis region. In the suburbs, suburban communities along the Missouri River. What are the incentives for local officials to pursue development in those areas?

General Gerry Galloway 16:24

Well, the incentive for them to proceed with development is their constituents want it. And I’m a lover of water. I’m a lover of rivers. And I’ve met river rats in across Wisconsin and in Iowa, who live along the river and don’t want to move out of the way. They’re willing to take a chance that one year out of thirty I may get flooded. But I want to have that. So I can sit on my front porch and see the river go by. And the fascinating part, the wonderful part of living on the Mississippi and Missouri to a degree is watching the vessels go by. Seeing all of this transportation taking place. Looking at recreation. Having recreation. All of these things make water a wonderful thing. You just have to appreciate that it can come and get you. And and, there are people that can afford to be flooded. There are people that can’t afford to be flooded. And we have to figure out what are we going to do about the difference in those two groups. And that’s an issue of the National Flood Insurance Program.

Dean Klinkenberg 17:32

And I do want to get to that in a couple of minutes too. One of the things I’ve always been curious about is sort of that balance between what people perceive as the benefits of living in in the floodplain versus the potential risks. And it seems like there’s still a fairly common attitude that if there’s a levee, that there’s really no risk. How do we…What’s happened in the past thirty years to sort of help people understand the actual risks that exist in floodplains, even when there are flood protection measures in place or structures?

General Gerry Galloway 18:05

Well, we that’s a very difficult question. And it’s one that, again, is mired in politics. We did not in the ’93 report make a big case for risk and that risk ought to be identified. We said everybody ought to have insurance. People that are living near the floodplain even behind levees needed to be cautious. And we made that point after Katrina in 2005. The nation, because in ’96 and ’87, ’93, around the world, we had big floods, we said what we ought to make the assumption that if you have a levee there is no guarantee that it’s not going to get over top. You can have a 100 year levee, a 500 year levee? Well, first of all, we know now that the whole concept of computing, the return interval for a flood is bogus. It does not work. The climate change has caused the hydrology to be suspect. So we can’t tell you exactly what it’s going to be. And so we’re saying that there’s no such thing as absolute protection and you better be prepared for the levee to fail or overtop, and all of the focus within major organizations, especially the Core and the Bureau and, and others is on how fragile is the system? What is the fragility index for the levee? Are you liable to find a car in the middle of the levee? Are you likely to find when they initially built it that they made some really bad mistakes or that they’re not maintaining it. And that’s the one and that happens a lot on the Missouri, where you have communities that can’t afford to have a very vigorous flood levee maintenance program. But out of Katrina came the idea that we’re gonna go to risk, and that everybody has a risk. It’s just how great that risk is. And you have to determine that and there are many things you can do to determine that. You can look at the levee, you can understand where it is, you can see how close you are to, to a source of water. Who’s upstream from you? As we’ve seen in many places, because the river doesn’t overtop the levee doesn’t mean the people living behind you on the little streams that at the time you thought were little streams suddenly become gully washers and fill the area behind the levee, and the pumps inside the levee don’t get the water out. We had that again, after Katrina in New Orleans, they were repairing a number of the pump stations. And the pumps were out and it poured down rain in an area that should have been protected, we spent $15 billion on protecting it, was flooded, because internally, they hadn’t taken care of the problem. And so that risk is there. And people need to understand that it’s very hard to get people to deal with that. The states are now really concerned about the other part of that is I live upstream, we’ll say from you, and you live in a levee near a big river. But I live on a smaller stream or a river upstream. And I’m solving my problem of heavy rainfall. So I’m going to get a system that really gets rid of all my water. And where does it go? It goes to you and and how do we prevent me flooding you? The state of Louisiana has looked very hard at this and has discovered that in a community, when you’re looking at it, there can be ten, fifteen, twenty agencies that have the right to dump water off their property into a river and cause harm downstream. The “cause no harm” concept is one people ought to understand and look to.

Dean Klinkenberg 21:43

Can you say a little bit more about that? “Cause no harm” concept? Like, how, how do they actually implement something like that?

General Gerry Galloway 21:50

Well, that that’s a fairly interesting one. And it goes back to, I can stop the water from leaving my property or leaving my neighborhood or my community by building retention ponds. And I’m going to jump for a second into something that is so far away from us. That seems to be something you might not want to consider. But we have to consider the Chinese in about 2012 or so they had a major flood in Beijing and the President Xi Jinping said, “I don’t like this idea of a whole bunch of people being killed. Millions, billions in damages in my city. I want you to get rid of the water and hold it here in the city in places not send it downstream and flood other people not let it flood you inside”. And so they’ve launched a program that they hope to be completed in mega cities, and a mega city for them is thirty million people. So you can see they’re dealing with big issues, where seventy percent of the water that falls on that community is retained in the community either in underground storage, in wetlands. I’ve been to four of the cities like that. And the people love it because there are parks or recreation areas, they’ve had to take down some buildings in order to do it. But it’s a lot easier for them to do that. I mean, they don’t have much choice in that. But they did that. The concept has been tried in some of our cities on a smaller basis. And so you can have retaining ponds, you can have retaining ponds for a golf course you can have retaining ponds for an area that has a lot of parking lots or has a lot of concrete on the ground, that’s going to cause the water to run off. You got to find a place to store it and so you can gradually let it out into the river and not cause harm downstream.

Dean Klinkenberg 23:49

Dean Klinkenberg here interrupting myself. Just wanted to remind you that if you’d like to know more about the Mississippi River, check out my books. I write the Mississippi Valley Traveler Guide Books for people who want to get to know the river better. I also write the Frank Dodge Mystery Series set in places along the Mississippi. Read those books to find out how many different ways my protagonist Frank Dodge can get into trouble. My newest book “Mississippi River Mayhem” details some of the disasters and tragedies that happened along old man river. Find any of them wherever books are sold.

Dean Klinkenberg 24:26

Seems like that’s a, pardon the pun, but like a sea change in our, in the way we think about managing the Mississippi, too. Wasn’t the idea for a couple of generations – we want to move the water down the channel as fast as possible to mitigate floods.

General Gerry Galloway 24:43

Yes, yes. And that was the way up until 1927. When the flood occurred then. And then is after ’27 that the Corps of Engineers went to the multipurpose way of dealing with things. They came up with a major reservoirs downstream of you. There are some in the hinterlands of Missouri and Illinois and Iowa that retain water above the big cities. And that’s useful. But again, in 2011, on the upper Missouri, we had a massive rainfall and snowmelt at the same time. And all of these, six of the largest dams in our country were filled with water and there was nowhere for the water that was still coming to go, other than to get out of the banks and flood the people that in places in North Dakota and Iowa and many other places in the area. And you saw the same thing in a more recent flood where the people around Omaha were flooded by the Platte backing up. So it is not easy to figure out how you can store all the water. Another thing that’s been done and the Dutch are getting a great deal of credit for something called “Room For The Rivers”. They are taking people away from the edge of the river and using that to store water when the water is very high. But the Dutch Ambassador explained to me that they learned that from us on our 1927 flood control, because as you go down the river south of Cape Girardeau, you will see that a lot of the land there is set aside for storage, and that there are areas where the lower Yazoo, the lower White, are when you have a big flood on the Mississippi, they expect to be flooded. They know that but it’d be not very often, but it’s going to happen. Now, how do we make? How do we give recompense to people who get flooded by that? They tried that north of Sacramento when Sacramento, California was flooding. They said, “let’s buy up farmer’s land and flood it but get an agreement.” The problem is that land isn’t very valuable now or is only valuable for agriculture, which does have a return. But most everybody has in their mind, someday I’m going to develop that into 500 homes, I’m going to make a billion gazillion dollars. And so people are reluctant to give up their land. So how do you balance all of this, the desire to let people own their land very important in our country, and do what they want with it, and not have it taken away from them. And the idea to protect somebody else downstream by using that land. And that’s the whole issue of wetlands. We’ve talked a lot about preserving wetlands, because they are great storage. But we said in the ’93 report that even if the wetlands that had been destroyed over the years in the Mississippi Basin had been there, they wouldn’t have prevented the flood of that nature, because it was so much water. It’s like the sponge. At a certain point, a sponge can no longer hold water. It’s going to overflow, anything you pour on that sponge is going to run off. And so we have to and that’s what we’re struggling with right now, with our concepts of design with nature and wetland retention is how much can you do with that? And how much are you willing as a citizen to accept as that level of protection from something that will work some of the time, but won’t work all the time?

Dean Klinkenberg 28:06

Right? Because we kind of have an expectation that things should work all the time, right? It’s hard to address that attitude. These are very difficult issues. They’re part of this is they’re all these issues with local control over what local communities do with their own land. But we also know that those decisions they make locally can impact other communities. So who…what are the levers we should be, or what are the different levels of government that should be involved in making these decisions? Who’s doing who should do what who is doing what?

General Gerry Galloway 28:45

We said is it’s everybody’s responsibility. The locals, the people who live in the floodplain, the state and the federal government. We are doing a terrible job of working that particular problem. We don’t have anybody in charge at the federal level. We abolished the…we didn’t abolish, in 1981 when President Reagan took over, he did away with the Water Resource Council. In funding, he zeroed out the funding. So it hasn’t operated other than for a couple of hours since 1981. So there is nobody that’s coordinating the efforts of the federal agencies in water resources, and that you have to have that because you’re dealing with all the agencies have a role in that. Where HUD builds its homes, where EPA wants to have wetlands, where FEMA thinks the floodplain really is. All of these things need to be addressed. And we don’t have anybody in charge we have every once in a while we’ll bring together the assistant secretaries of the departments and they’ll all get together and say Kumbaya, we all are going to hug each other and then six weeks later, they’re not talking knew each other. And it’s it is a real problem. I will say, In defense of President Biden, he has really worked hard to have them and have his people make them work together, which is an important aspect of that. Second, we don’t do a good job of coordinating among, and with the states at the federal level. Too often, when you realize the National Flood Insurance Program is almost me living in Washington DC, going directly to you in Cape Girardeau. With that, that was very little action at the state level, to tell you what to do, how to do it, inspecting you, having you use my standards, using the things that I’ve prepared. And the states that reasonably in some cases have said, “Alright, Mr. Federal government, you want to do that, Mr. Federal Government, you run the show and I’ll sit back and you come support us with dollars when the time comes”. We also are overly generous without realizing it. We built lots of things in terms of flood control. For the at the federal level, it was initially started off to deal with the big disasters, the Mississippi Flood of ’27, and national floods in ’36. And then afterwards, you started getting into smaller communities, because the law does say, when the benefits exceed the costs, the federal government can take a responsibility. It didn’t say it has to, it doesn’t say what level, but it’s been assumed to be that case. And so that becomes a challenge. What are we going to pay for and then at the same time, my good friend who has a farm in Iowa, it gets out with his, he’s near the shoreline, he wants to keep a crop going. So he gets his grader out there and grades it and builds a small wind row levee, and he gets an extra crop one year and at not having it underwater. And then it’s built up a little bit more. And pretty soon, there are fifty houses behind that. And then the local government says, “well, we ought to take charge of that it will form a levee district or utility district”. And the state sort of either closes its eyes or decides that’s okay, that’s tax revenue. And you go on from there. And so we are not dealing well in a coordinated fashion with how we’re gonna protect against flooding.

Dean Klinkenberg 32:26

Right? Those seem like very difficult problems to address. So like you’re the farmer, you you mentioned that, on the one hand, it’s his private land. So he probably thinks why shouldn’t I be able to build a little bit of an extra berm to keep water out so I can grow more crops? What are the checks and balances at that level to prevent individuals from doing things that might have bigger repercussions throughout the whole system?

General Gerry Galloway 32:51

Well, you’re absolutely right. And how do you do that? It’s fine to build your levee. And it’s fine to let people move behind it. But they all ought to know that if something goes wrong, it’s their problem. But what do they do? They look to the federal government to bail them out. What does your local congressman do? Bless them. They’ll say, well, what can we do that certainly we have emergency restoration. We have restoring, actually rebuilding the levees something called PLl 84-99. Which allows the federal government to come in if the levee has been kept up to speed and do the repairs for you. Well, all of these things are okay, we’ve got a few levees. But when you got levees all over the country, or worse than that, you don’t know where all the levees are in the country. Because states don’t have accurate counts. They don’t worry about it. Some states are oblivious to it deliberately. And other states like California are very, very close to what’s going on and see what’s what they’re looking at and what they have to worry about. So there are interesting challenges. And let me toss into this on top of that we didn’t consider in ’93 and didn’t really consider in ’95, other than the fact that the levees were involved is what about these massive rainfall events that we’re having, where we have these cloudburst storms, where you get and Harvey really is one of those where you get fifty-six inches of rain or as just occurred in the Northeast United States or as occurred across the country in Iowa, Missouri, where you have an intense rainstorm. And the the flood protection is built for the river. And nobody really has thought about what happens when you can’t handle that with your city flood stormwater system. And so you get flooding downtown. It floods basements and floods, stops the roads in other places that keeps people from going to work and shuts down restaurants. It puts the poor at a disadvantage. They can’t get to work. They don’t get paid if they’re not there, yada yada and so So, we have this new, interesting challenge throughout the nation of these intense rainfall events that are affecting the urban areas. And again, it’s the poor people that are dealing with this the most. And, and so, again, but we have to be able to deal with it as a system. And nobody’s really figured out that, oh, I’m in charge of that. No, that must be somebody else. It’s your problem, not mine.

Dean Klinkenberg 35:26

Right. And those are like, these issues have kind of different dynamics with them too like the intense rain events you’re talking about. We’ve had a few of those here in St. Louis. In 2016, at the end of the year, we had a freak storm system that came in and dumped several inches of rain over a wide area and the Mississippi river rose very fast. I think, in one twenty-four hour period, it went up ten feet in December. And by January 1st it had crested at the third or fourth highest level on the St. Louis gauge. We’re not supposed to have rain like that in the middle of winter. But here we have this very intense rain event. And since then, we’ve had a couple of other very intense storms that have flooded city streets around me and caused a leak in my own roof last year. But that’s a little different than people who live in the floodplain where there’s a reasonable expectation that, you know, at some point, the river is going to try to stretch itself out and and fill some of that land again. That’s a little bit more of a predictable risk it seems to me. Is that a fair way of thinking about it?

General Gerry Galloway 36:31

Unfortunately it’s not, and all around the world we are having a problem with this. I’ve been working with the Swiss. They have somewhat the same problem we have in mountainous areas. When they have a rainfall and big rainfall event, it can come in and swamp the cities. And so they’re putting out maps that show everybody in not at the gradient of a foot or half a foot, you’re in an area that is high risk. There’s there’s a probability that if there’s a huge rainfall event, we can’t tell you when it’s going to occur, but you’re gonna get wet. And we’ve had people drown in their homes in the basements. Know that you need to get out of there. Know that you need to take the things that are important to you out of there. Maybe you don’t want to store your shoes in your house underground. You want to have it with somebody else. Take care of yourself, think these things through and recognize that it’s getting worse. You talked about to your friends in New York before. When we had Sandy, there are places in New York City that it looks like measles where they flooded because the land had settled over the many years. The sewage system had broken. The whole area was not capable of moving the water that they needed out of the area. And we still have places in New York City where people are suffering from the results of Sandy because we don’t have the money to go through and do all of these repairs. That are as you said they seemingly are predictable. And but again, they’re costable too. And that’s the problem. It’s not easy to say, take care of all these problems, and mayor’s would probably love to do it.

Dean Klinkenberg 38:15

Well, and that’s part of the bigger problem here too, is you know, we don’t have the money to fix all of this everywhere. We have to make some decisions. And sometimes it’s the federal government, or oftentimes we look to the federal government to pay for those kinds of repairs or infrastructure. How are we making decisions about when and where to spend money? You know, there’s limited resources.

General Gerry Galloway 38:38

Well, you put your finger on the big word called “priority”. Who has the priority? How do you decide where to go? And it’s not just who do you help with a levee, it’s we’ve got to worry about hospitals, we have to worry about roads. Every time I go down a road and I see these large sound barrier walls going up and clearing of huge areas, I wonder is that priority higher than the person that lives in Hamburg, Iowa that needs to have the levee repaired? Because we don’t have the money that Congress has said, we’ve got a $50 billion deficit in terms of our levee and dam repairs, and we’ve got to be doing something about it. And, and so we wait till there’s a crises or we wait till there’s been a flood, we go back in and try and repair it. So how do you decide that? Again, isn’t that in part a state and local responsibility? And that goes back to what you asked some time ago is, is how do we balance out after you have a flood? What should you do and what should people do? They ought to be paying for their insurance based on the risk they face. People don’t like that. Because there are those who would say everybody has the same risk. No, they don’t. That’s for sure. You’re right at the bottom of the levee. The levee is not maintained well. You can see the the boils that are at the base of the levee. You can see animals crawling around on the levee. In some cases, we’ve had big fights over trees that people built. I was in a place in New Orleans where they had a jacuzzi built into the side of the levee. Well, you know, give me a break. So how do you how do you do this, you have to figure out a way to get people instructed, and in the federal and local officials to support these sorts of programs.

Dean Klinkenberg 38:38

So let’s talk about the Flood Insurance Program a little bit then too, because that was a big component of the report as well, in ’93. I know we we’ve had a few changes that have happened since then. For one thing, it’s a lot harder to make claims after repetitive losses now than it used to be. Did we change the waiting period? Before, I remember, I had friends in the floodplain in Illinois, who were able to buy insurance, and in five days they had coverage.

General Gerry Galloway 41:00

That we changed that and that was a good. There have been a number of changes. The problem with insurance is FEMA is run by a board of directors of 535 people. Each one of them has an interest in not causing any pain to his or her constituents. And in 2010, we began to look at risk based flood insurance. And in 2012, the Congress went along with this and passed a law that said we’re gonna make risk based and in 2014 they repealed that because everybody said, “Oh, I’d have to pay an awful lot”. And it would be in Lafourche Parish, Louisiana. Most of the people would not be able to sell their homes because the insurance would be so much for the person that was buying it, they wouldn’t want to buy it. And the same thing happened in the coast of Massachusetts, and along the eastern shore of Maryland, and mostly in coastal areas. But again, the idea that if you lived in a risky area, you’d pay more became unacceptable. Again, there were people that couldn’t pay. FEMA did a study, and they came up with this study that said we need to supplement. We need to have some way to subsidize the insurance for people below a certain level. We have lots of housing programs. And why don’t we just do that? You know, that’s 2015 that the study came out or ’14, we haven’t done anything with it. We were just talking about it. So it’s who can afford insurance. If they can’t afford it, what do you do about it? Unfortunately, the people that are most at risk are the people that can’t afford it. And so if somebody lives on the eastern shore of Maryland, where I go to the beach, and they have a $500,000 house, and they insure it, and they already get $250,000 from FEMA if it gets wiped out, they still have the land, and the land was worth in the market today, half a million dollars itself. So they weren’t worried about it. But the kid or the young family or the farmer down in North Carolina that lives near the coast and gets wiped out and his farm is no longer there and he doesn’t have insurance, he’s toast. And so we have a problem. We haven’t been able to figure out what’s going on, we’re willing to put out a lot of money to the people that have got a lot of money, but we’re not willing to put out money to the people that need it. And we’re still struggling with where do you need flood insurance in? And how do you deal with this issue of you say I’m flooded, because I’m at 101.3 feet above sea level, and I should be at 102? And so you give me a hard time. We don’t know that. It’s plus or minus something. Ridiculous. But Congress wants a number. And that’s and so they’re much more happier when they can say, well, we have this very interesting algorithm developed by FEMA and the insurance agencies say this is what it is. So that’s what you have to do. Other countries have taken to saying everybody should have insurance. It ought to be part of when you buy a house, you have to buy insurance. The federal government supports it, but it’s not for everything. You have to make wise decisions, but we’re not up to making people make wise decisions.

Dean Klinkenberg 44:29

Right? Well, and the National Flood Insurance Program, if I remember this correctly, anyway, the reason we have it is because private insurers wouldn’t insure houses and some of these markets, right? Because it was they knew they were going to lose money, insuring these properties so nobody can buy private insurance. So we have a federal flood insurance program for those areas. But we don’t really have a mechanism. Correct me if I’m wrong, there’s not really a mechanism to force people to buy flood insurance in areas that we know have some risk of flooding.

General Gerry Galloway 45:06

We do. The mechanism is mandatory insurance if you live in a 100 year floodplain. All right. But again, the question I ask is, “what’s magic about the 100 year floodplain?” We had 154,000 homes flooded in the Houston area during Harvey. Sixty-six percent of those were outside the 100 year floodplain. In other words, if you’d, if you had been a good person and bought it if you were in the 100 year floodplain, then you got it. But if you didn’t get it, because you’re outside the 100 year floodplain, you got flooded. Nevertheless, it was we don’t, we don’t know what’s going to flood that well. And so that’s that’s a problem. Mandatory; people have talked about make it mandatory for 500 year, but we don’t know what the 500 year is. What you really have to deal with is, what is the risk that you’re willing to take? The community has to sit down? Why not. People have suggested why not have the community buy insurance for everybody. And because then everybody is paying for that you have a logic to say, “I’m not going to let you move into an area that is at risk because you’re going to cost all your neighbors money because our insurance as a community is going to go higher”. We’re getting to be very precise. Some of the recent calculations with computers tell us “Oh, you’re at 103.3.” Nonsense. But that’s what we sell, that you can figure out, well, I’m really not that much at risk. No, you don’t know that. And that’s the problem. We also have on top of that all these FEMA maps deal with the non urban flooding, they deal with the riverine flooding that comes up. They deal with the coastal flooding that comes up and these gully washer events are causing as much damage as the big river floods.

Dean Klinkenberg 46:57

Right? So the example that you just mentioned about the community pooling their resources together to buy insurance for the whole community, is that happening anywhere?

General Gerry Galloway 47:06

No, not that I know of. I mean, we keep talking about it. Every meeting I go to. The Association of State Floodplain Managers are working hard to get people to consider these alternatives. To get insurance mitigated, if you will do this. If you’ll raise your house. There are ways now when you are flooded and you’re going to repair it, you’ll get a chip to raise your house. And so the next time it won’t flood. And obviously, relocation is the federal government’s willing to support. But again, it’s very difficult to get people to buy in because if you get too much relocation, the community says they begin to suffer by loss of the tax base.

Dean Klinkenberg 47:50

Right. And they aren’t paying the price so much of the flooding if the federal government is coming in to repair things. You have the money being used to repair the community is coming from federal funds, the risk to the local community is less anyway,

General Gerry Galloway 48:07

Many, many communities are around the world, not here. But in the US, although there are some cases of this, the word retreat is being used. That’s it. That’s a four letter word, I’m sure in Missouri. The idea that you live in an area that is periodically in flood, why don’t you move back somewhere that’s not going to flood. Then you know that you’re not going to flood. However, we just had, again, we have these floods, intense rainfall events that are now putting that to shame, the idea that you can completely avoid the risk of water.

Dean Klinkenberg 48:48

Given the problems that we’ve had with the National Flood Insurance Program, has it outlived its usefulness?

General Gerry Galloway 48:53

Yeah, I would like to tell you that I have an answer for that. But the problem is I don’t have a solution if we were to move it out of the way. Because we’re not about to tell everybody to go to the insurance companies because they’re gonna really charge you a pretty hefty fee. We were talking about 15 to $20,000 a year for insurance for people in Louisiana that could hardly afford to pay their rent. And the private insurance is not going to be “oh, well, we’ll be nice. Well, we’ll give them a discount.” We know that they’re going to flood. That’s why they stopped insuring because when you have a flood, it all happens in one area. And their losses are tremendous. Insurance companies are backing out of Florida. Florida had to go to several aspects of their insurance to a Florida supported insurance program. Because it’s just not feasible for the insurance company to deal with this risk. Insurance people recognize risk, we don’t.

Dean Klinkenberg 49:03

Right. Well and it It seems like it’s partly the political leadership isn’t willing to tackle that risk head on either and manage that in response to what’s actually happening on the ground.

General Gerry Galloway 50:11

Yeah, you’re right. It’s, but I’m going to say that this is hard to say for the people that are flooded. It just doesn’t come up on the radar screen. There are so many other problems you have in a community that, okay, we might flood, okay, that neighborhood down there is gonna get really wet. But I can handle that. I’ll still get elected. And, and it’ll still be okay, that community won’t fail. It’s when you get a Houston, or you get a New Orleans that the federal government has to step in with billion dollar replacements.

Dean Klinkenberg 50:47

Right. And in fairness to some of the communities like you know, Louisiana, in particular, there are people that have been there for a long time and the risks have increased with the loss of coastal wetlands that have increased their exposure to big storms. It’s not all that people are just moving into those high risk areas now. There are in some communities people who have been there a long time.

General Gerry Galloway 51:09

And if you want to go down to coastal Louisiana, and I’ve gone up and down the coast. We have oil rigs out there that are keeping us warm in the winter. We have fishing out there that is terribly important to the economy in the US, plus also our stomachs as you get this good food. And the people that do those sorts of jobs have to live reasonably close in. We have oil refineries on the coast of the gulf all the way from Texas over into Alabama. And, again, those are part of our economy. And so the people that work there, have to have some sort of protection, and we’ve got to figure out what to do for them.

Dean Klinkenberg 52:03

And now it’s time for the Mississippi minute. Well, in this episode, I want to do something a little different. We are marking thirty years since the Great Flood of 1993. I have some very specific memories from that. I remember I was in downtown St. Louis at a wedding, right at the time the Mississippi River crested at St. Louis at just under fity feet. There were a lot of people downtown at the Arch. The water had crept up as I recall about two thirds of the way up the steps. Maybe it was a third, my memory might not be great about that. But it was certainly higher than anybody had ever seen the water in front of the Arch. There was chaos further west. The Monarch Levee had been breached out in Chesterfield, and Highway 40, the main thoroughfares, and the region was underwater. I was wondering what memories you have in the great flood of 1993. If you have a story you’d like to share, I’d love to hear it and maybe even write it on the podcast in the next episode. In two weeks I’ll have part two of the interview with Gerry Galloway and I would like to be able to include some personal stories about your experiences with the flood. If you have something you want to share, get in touch with me at MississippiValleyTraveler.com/contact. Or you can just send me an email direct to [email protected]

Dean Klinkenberg 53:30

Thanks for listening. I offer the podcast for free but when you support the show with a few bucks through patreon you helped keep the program going. Just go to patreon.com/DeanKlinkenberg. I’d be grateful if you’d leave a review on iTunes or your preferred podcast app. Each review makes a difference and helps other fans of the Mississippi River and the Midwest find this show. The Mississippi Valley Traveler Podcast is written and produced by me, Dean Klinkenberg. Original Music by No Offense. See you next time.