Introduction

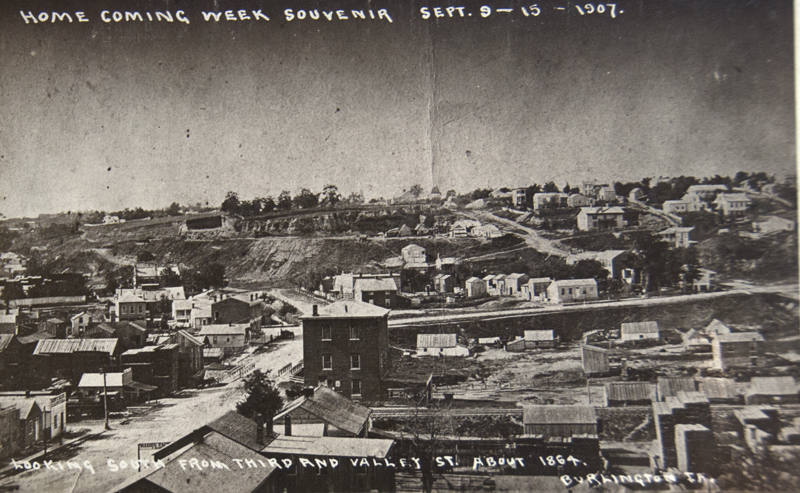

Burlington was built in a bowl-shaped depression at the end of a ravine that opens up at the Mississippi. As the city grew, folks built up, over, and around the hills, expanding into the prairies that spread out from the bluffs. Visitors will find most of the attractions concentrated in the flatlands and hills of the original city center and along the riverfront.

Visitor Information

Visitors can stop at the Port of Burlington Welcome Center (400 N. Front St.; 319.752.8731) on the riverfront to pick up flyers and advice.

History

The area around what we now call Burlington was known to the Sauk and Meskwaki Indians as Shok-ko-kon (Flint Hills). In 1824, when the Sauk and Meskwaki ceded title to lands in Missouri, a special zone was created in part of southeast Iowa. Known as the half-breed tract, 119,000 acres were set aside for people of mixed Indian and European blood. The future cities of Burlington, Fort Madison, and Keokuk were part of this tract. Under the terms of the deal, mixed-race inhabitants could own but not sell the land. Ten years later, the US government granted them all the right to sell their property, which triggered a period of chaos and confusion.

Speculators swarmed in and bought land, sometimes for as little as a barrel of whiskey and a pony; some bought titles from folks who claimed to own land but really didn’t. There were no official land surveys, so boundaries between claims often overlapped. Individual tracts were sometimes sold to multiple people and squatters moved in to claim a piece of the action, too.

The Wisconsin Territorial Legislature tried to sort it out in 1838 but with little success. Hugh T. Reid believed he bought the whole 119,000-acre claim in a sheriff’s sale in 1842 (for $2,884.66), so he sued Joseph Webster in a dispute over 160 acres. The US Supreme Court essentially invalidated Reid’s claim in 1850, which meant all the land reverted to the government. A district court divided the land into 101 parcels and divvied it up by partition decree. People with claims drew lots, literally: the parcel each got was determined by a random drawing. One of the attorneys in the case, by the way, was Francis Scott Key, the author of the Star Spangled Banner.

Before all those disputes over land titles, the American Fur Company established a post at Burlington in 1829, staffed by Amzi Doolittle and Sampson White, both of whom probably commuted across the Mississippi to homes in Illinois. Just two weeks after the Sauk and Meskwaki nations ceded six million acres on the west side of the Mississippi River in 1832, Doolittle and White (along with Morton McCarver) made a premature attempt to claim part of the land, even though they could not legally do so until June 1833. Others tried, as well, but were driven out by the army before winter. A persistent group that included McCarver, White, and Doolittle tried to claim a site for a new village—again too soon—but any claim they had was essentially nullified in 1836 when the US Congress passed an act for the platting of Burlington and other towns.

After the Congressional act passed, Dr. William Ross was hired to complete the first survey. He is sometimes called the Father of Burlington, not just because of that survey but also because he was the first doctor in town, half of the first marriage, established the first church, the first post office, and probably milked the first cow, too.

John Gray purchased the first lot after the survey was completed. Along with his lot he got naming rights for the new city—quite a bargain! He went with Burlington because he had previously lived in Burlington, Vermont. His choice wasn’t universally loved, but attempts to replace it with a different name faded by 1850. Incidentally, Burlington has had its share of nicknames. One of the most common was Catfish Bend, which wasn’t initially meant as a compliment, but which you’ll find today attached to a casino. Presumably, the nickname Orchard City pleased more people.

When Burlington incorporated in 1836, some 500 people called it home. The city’s initial board of trustees was composed mostly of men looking to make money, a typical setup for pioneer towns, men like George W. Kelley who had been a squatter and just wanted to get his claim recognized. The newly formed Iowa Territorial government chose Burlington as its temporary capital in 1838, but the permanent capital was established at Iowa City at the end of 1840.

Many of the early European and American residents had pro-slavery views, partly because of trading relationships along the Mississippi with slave-holding states and partly because some had roots in the South. When news trickled upriver that the abolitionist Elijah Lovejoy had been killed at Alton, Illinois in 1837, a cheer erupted from a crowd on the riverfront.

This might also explain why the state did not welcome black residents with open arms in the early years. Black men couldn’t live in Iowa Territory after April 1, 1839 unless they had papers to prove they were free and could post a bond of $500. In early Iowa, like in many other states, blacks could not vote, could not marry whites, could not serve in a militia, could not attend public schools, and could not testify in court against a white person.

As Burlington grew, many of the founders moved on, including Doolittle and White. The city they left behind expanded into the surrounding hills. Three hills were named after a cardinal direction (North, South, and West). Vinegar Hill acquired its name because of a vinegar factory, but as wealthy people moved there, it became known as Prospect Hill, which sounded like a more pleasant place to live.

Early Burlington was so well known for its pork processing industry that some folks nicknamed it Porkopolis (yet another name for Burlington!). After the railroad bridge was completed in 1868, Burlington lost much of its pork processing industry as live pigs were shipped by rail to slaughterhouses in places like Chicago, St. Louis, and Omaha. The city also had flour mills, lumber mills, wholesalers, carriage manufacturers, shoe makers, a barbed wire manufacturer, and department stores.

While we have many romantic images of river towns, life along the Mississippi River in the early days was far from ideal. The Lower Town section of Burlington was littered with animal feces, broken crates, empty bottles, spoiled and rotting food, discarded animal bones, and other sorts of trash. Butchers threw animal guts wherever they wanted. Hawk-Eye Creek was an open sewer for decades, discharging all that crap into the Mississippi. Passing steamboats dumped their trash on the levee, too. I’ll leave it to you to imagine what you might have smelled walking around the city in those days.

In spite of the foul smells and trash, by 1850 Burlington was a major transit center. In the spring of 1851, a thousand wagons were ferried across the Mississippi to Burlington. Hundreds of steamboats landed, carrying thousands of passengers. The Peoria & Burlington Railroad reached the area in 1855, then merged with the Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy (CB&Q). The railroads brought thousands of immigrants from around the world to Burlington, mostly from Europe, but many from China and Russian, too. Residents of Burlington could go to the train depot to witness the mass migration and enjoy some fascinating people watching.

The railroad was a major employer in the region for decades. The CB&Q built repair yards at Old Leffler’s Station (its name was changed to West Burlington in 1883). At the time of the name change, West Burlington had more orchards than houses (9 to 8). The railroad closed the maintenance shops in 2004.

Burlington was an assembly point for Iowa soldiers during the Civil War, with troops garrisoned at Camps Warren and Lauman. The camps were poorly provisioned, though, and often not sanitary; locals helped supply food and blankets to the soldiers. By 1862, some soldiers had behaved badly often enough that a curfew was imposed for enlisted men; other soldiers patrolled the streets to enforce it. During the Civil War, all goods that moved through the city were subject to inspection. Any contraband (medical supplies, arms, gunpowder) that authorities suspected was intended for the Confederacy or its sympathizers was seized. Inflation drove up the cost of most goods and a lot of farmers were fighting in the war, so many fields were not planted. Times were hard and food scarce.

After the Civil War, Burlington grew rapidly, from 6,700 in 1860 to nearly 15,000 ten years later. The new arrivals came from diverse backgrounds. Germans were the most numerous, but a large number of Swedes also settled in Burlington. Irish immigration peaked between 1860 and 1890, with many Irish immigrants finding work at the Murray Iron Works or at Embalming Burial Case Company. Congregation B’nai Sholem was founded in 1879 to serve the city’s growing Jewish community.

By 1875, Burlington had 300 black residents; the community grew larger between 1880 and 1920 when some coal and railroad companies brought African Americans from the South to work as strikebreakers. While whites contributed money to help build some of the city’s African American churches, the city’s social life was mostly segregated, with separate seating in the movie theater and segregated swimming pools and bowling alleys. Many hotels wouldn’t serve black customers.

In late 1800s, the most common crime leading to arrest–by far–was drunkenness, but there were other ways to get in trouble, too. In 1872, youthful skinny-dipping and speeding drivers accounted for more arrests than prostitution and gambling.

Other than drinking and skinny dipping, entertainment options in the 19th century included attending lectures (phrenologists, doctors, travel lectures), going to the circus (it must have been quite a sight to see elephants drinking from the Mississippi!), minstrel shows, magicians, panoramas, masquerades and costume balls, organ grinders, street preachers, fishing, and hunting.

For adults or precocious teens, another option was heading out to a gunboat. From the Civil War until around 1880, gunboats—floating brothels—would tie up for long periods of time at places like Burlington. They served cheap liquor at inflated prices; prostitutes charged whatever customers would pay. They really answered to no one. If they ran into trouble, they would simply lift anchor and float away to a new location. Gunboats often undermined land-based brothels, many of which had worked out good deals with local law enforcement.

Well into the 20th century, Burlington had a stable manufacturing sector, with factories that made sparkplugs, backhoes, and batteries. The Iowa Ordnance Plant (later the Iowa Army Ammunition Plant) opened in 1941 on 20,000 acres west of Burlington. At its peak in 1941, the plant employed 12,000 people. It manufactured mortar shells, artillery rounds, and bombs. During its first two years of operation, the plant had two major explosions, the first killing 11 people and the second killing 21. The plant is still operating today, building large caliber munitions for the Army, but with fewer fatal explosions, at least at the plant.

Beginning in the 1930s, residents could take the Chicago, Burlington, & Quincy Railroad’s four-car Mark Twain Zephyr along the Mississippi south to St. Louis, a trip that took about 5 ½ hours. Each car had a name: the Injun Joe carried the mail and the engine; the Becky Thatcher carried the luggage; the Huckleberry Finn was the dining car; and the Tom Sawyer housed the passengers. Service ended around 1960.

Burlington produced a number of people who had an impact on your life, even if you didn’t know it until now. Wallace Hume Carothers (1896-1937) invented the polymer we now call nylon. William Frawley (1893-1966) was an actor whose most famous role was Fred Mertz on I Love Lucy. Robert Noyce (1927-1990) was the co-inventor of the semi-conductor chip and founder of Intel. Legendary guitar player Bo Ramsey was born and raised in Burlington. Those are just the famous ones. Burlington produced quite a nerdlet of scientists.

Burlington native Aldo Leopold (1886-1948) wrote a widely influential book (A Sand County Almanac) that revolutionized conservation politics and policies. One of his more memorable quotes:

We abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.

–from A Sand County Almanac, 1949).

In the 1970s, Burlington was home to a variety of manufacturing plants: Chittenden & Eastman Company (mattresses), Winegard Compay (antennas), Case Construction (tractors and backhoes), Drake Hardware (wholesaler), Burlington Basket Company, Lehigh-Leopold Company (office furniture), Trane Company/Murray Boiler Division, Champion Spark Plugs, Bonewitz Chemical Services, General Electric, the Burlington Paper Company, and more.

Forty years later, manufacturing remains a key part of Burlington’s economy—Case Construction is still turning out backhoes and other heavy equipment and Winegard still makes antennae and satellite dishes—but companies are smaller, the jobs fewer, and most of the remaining manufacturing jobs require more than a high school diploma. Riverboat gambling began in Burlington in 1991, but it has since relocated in to a land-based casino. The largest employer in the region, however, is now Great River Medical Center.

Exploring the Area

The Des Moines County Heritage Museum (501 N. 4th St.; 319.752.7449), in the ornate former public library, showcases the county’s history in nine rooms spread across three floors. Expect exhibits on agriculture, the military, and Native American art.

The Garrett-Phelps House Museum (521 Columbia; 319.752.7449), built in the mid-19th century for William Garrett, has many original furnishings and also hosts a display of medical treatment artifacts (the house was converted to a hospital at one time) and the occasional rotating exhibit.

At the end of the 1800s, three German immigrants (Charles Starker, George Kriechbaum, and William Stehy) planned a street they hoped would provide an easy way to navigate the steep slope from Lower Town to Upper Town. Snake Alley—the “Crookedest Street in the World” according to Ripley’s Believe It or Not—opened in 1894. It twists and turns its way down 275 feet from Columbia Street to Washington Street with five half-curves and two quarter-curves. It turned out to be less practical than hoped, so the city scrapped plans to build more like it, but this one is still around. It’s a one-way street. Enter from Columbia Street and descend slowly.

For something a little different, go find Burlington’s two historic bells. In 1839, Father Samuel Mazzuchelli, the frontier priest/architect/future saint founded St. Paul the Apostle Church, building a church for the new parish the following year. In 1842, he bought a bell for the church. Two buildings and 170 years later, that bell is still calling out to parishioners at Saints John and Paul Church (508 N. 4th St.).

The other bell is at Parkside First Baptist Church (300 Potter Dr.) in a cloister behind the building. The bell was purchased by two former slaves, “Aunt Kitty” and “Uncle Ben” Sandridge. While enslaved in Kentucky, the two asked a Burlington man, a Mr. Wallis, to buy their freedom and take them to a free state, promising to pay him back. He agreed and took them to Burlington; within three years they had paid him back in full. When Aunt Kitty died in 1863, she left a bequest to purchase a bell for her church, calling it her Liberty Bell. The bell was installed in 1865 and later moved to its current location.

Our Lady of Grace Grotto at Saints Mary and Patrick Catholic Church in West Burlington (420 W. Mount Pleasant St.) was the Depression-era brainchild of two Benedictine priests, The Reverend M.J. Kaufman and the Reverend Damian Lavery. Using rocks donated by people from around the world and volunteer labor, they built an impressive grotto dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Parks Along the Mississippi River

Take a stroll along the Mississippi at Riverside Park (Front St.).

Crapo and Dankwardt Parks (2900 S. Main) are a couple of wonderful city parks atop the bluffs at the south end of town. Among their 150 acres, you’ll find an arboretum, the Hawkeye Log Cabin, a band shell, hiking trails, a swimming pool, and more.

Mosquito Park (North 3rd and Franklin Streets) is a small patch of grass atop a bluff at the north end of town that has a pretty darn good view of the Mississippi.

South Hill Park (Elm St. at S. 6th) has a good view of downtown and the river.

Sports & Recreation

Take in a game of the Burlington Bees, the city’s professional baseball team that plays in the Prospect League (Community Field: Mt. Pleasant St. just east of US Highway 61; 319.754.5705).

Starr’s Cave Park and Preserve (11627 Starr’s Cave Rd.; 319.753.5808) is a peaceful wooded area along scenic Flint Creek just north of town with a nature center and a couple of miles of hiking trails. Rock formations along the creek are rich with fossils and with a form of flint that is unique to the area that was once widely traded among North American Indians. The namesake cave is now closed to protect the habitat of its resident bat population.

The Flint River Trail is a multi-use trail that connects downtown Burlington to Big Hollow Recreation Area 20 miles to the northwest; some portions of the trail currently run along highways.

Culture & Arts

The Art Center of Burlington (301 Jefferson St.; 319.754.8069) features rotating exhibits that highlight the work of local and regional artists.

There’s truth in advertising at Weird Harold’s (411 Jefferson; 319.753.5353), which is a heck of a lot of fun to explore. Inside you’ll find costumes to rent, artwork, CDs, creative greeting cards, cassette tapes, 50,000+ vinyl LPs. They have a good selection of music made by local and regional artists. You aren’t likely to leave empty-handed.

Burlington by the Book (301 Jefferson St.; 319.753.9981) can set you up with a good read, including books by local and regional authors.

Getting on the River

There are some great areas for paddling close to Burlington (see the Toolesboro entry for more detail). If you didn’t bring a boat with you, River Basin Canoe & Kayak (13038 US Highway 61; 319.752.1857) can help you out.

Entertainment and Events

The Washington (306 Washington St.; 319.758.9553) is a fine venue to catch regional and national touring acts in an intimate setting; cash only.

The Art déco Burlington Capitol Theater (211 N. 3rd St.; 319.237.1099) hosts performing arts events, movies, and concerts. Hang out at the Night Cap Listening Lounge at the Capitol for a chill evening enjoying good music with your favorite drink.

Catfish Bend Casino (3001 Winegard Dr.; 866.792.9948) moved from a riverboat to a strip mall on Highway 61 a few years ago. Aside from the usual gambling options, the complex has an auditorium for concerts, a spa, and an amusement park called FunCity.

Farmers Market

A seasonal farmers market (319.752.6365) sets up along Jefferson Street downtown (between 3rd and 5th Streets) on Thursdays from 4:30 to 7pm from May through October.

Festivals

Burlington hosts a number of fun festivals, most of which take place downtown during the summer.

Over Memorial Day weekend, bicyclists race up, down, and around Burlington, including up the crooked street that lends its name to the event, the Snake Alley Criterium.

The Snake Alley Festival of Film showcases short films from around the world (Capitol Theater; June).

Artists’ booths wind their way up and down the crooked street for the annual Snake Alley Art Fair (mid-June).

The Des Moines County Fair kicks off in late July (West Burlington: 1500 Agency Rd.), complete with carnival rides, livestock judging, and fried foods.

In late September, Burlington celebrates its past with music, food, and historical reenactments at Heritage Days (319.752.6365).

** Burlington is covered in Road Tripping Along the Great River Road, Vol. 1. Click the link above for more. Disclosure: This website may be compensated for linking to other sites or for sales of products we link to.

Where to Eat and Drink

The Bean Counter Coffeehouse (212 Jefferson; 319.850.1939) is a good option for coffee and locally made snacks (or panini), especially if you’d like to hang out for a while. The interior is cozy and inviting with plenty of room.

For classic diner fare in a cozy setting, grab a counter seat at Jerry’s Main Lunch (501 S. Main St.; 319.752.3750), which has been pleasing Burlingtonians since 1946.

Wake N Bake Breakfast Company (713 Jefferson St.; 319.754.0494) is another popular option for breakfast or brunch. Get some donuts to go or enjoy biscuits and gravy on the large patio when the weather cooperates.

You won’t find a restaurant with better views of the river than Martini’s Grille (610 N. 4th St., 4th floor; 319.752.6262). The food is on the pricey side and while good, not quite what it aspires to be, but with those views you won’t really care. It’s also a good choice if you just want a couple of cocktails.

The classic Italian food at La Tavola (316 N. 4th St.; 319.768.5600) receives consistently rave reviews. The make a tasty pizza and offer an extensive selection of Italian entrêes. It’s a small place, so it’s a good idea to make a reservation in advance.

Where to Sleep

Camping

Just south of Burlington and a mile from the Mississippi River, Spring Lake Campground (3939 Spring Lake Rd.; 319.752.8691) is a full-service camping community, offering a variety of sites from RV hook-ups to primitive; the campground has a shower house, a swimming beach, and more.

Budget

Arrowhead Motel (2520 Mt. Pleasant St.; 319.752.6353) offers clean, well-kept affordable rooms close to US Highway 61 that are just ten minutes from downtown and the river. You can even walk to a baseball game. All rooms come with a small fridge, microwave, and adjacent parking.

Bed-and-Breakfast Inns

Squirrel’s Nest B&B (500 North St.; 319.752.8382) rents three rooms, including a penthouse suite with great views of the river. Guests rave about the full breakfast and the views.

Getting There

Amtrak offers service to Burlington. The California Zephyr route between Chicago and Oakland, California, has one daily stop in the morning at Burlington for trains headed to Chicago and a daily stop in the evening for the train coming from Chicago.

Resources

- Burlington Public Library: 210 Court St.; 319.753.1647

- Post Office: 300 N. Main St.

- Newspaper: The Hawk Eye (800 S. Main St.)

Community-supported writing

If you like the content at the Mississippi Valley Traveler, please consider showing your support by making a one-time contribution or by subscribing through Patreon. Book sales don’t fully cover my costs, and I don’t have deep corporate pockets bankrolling my work. I’m a freelance writer bringing you stories about life along the Mississippi River. I need your help to keep this going. Every dollar you contribute makes it possible for me to continue sharing stories about America’s Greatest River!

Burlington Photographs

A Song for Burlington

Burlington by Eric Pettit Lion (2014)

©Dean Klinkenberg, 2024, 2021, 2018,2013,2011