Gerhard Gesell emigrated to the US from Germany in 1863, an orphan eager to start a new life. He was the first generation in a family of high achievers in the United States. Patriarch Gerhard was a gifted photographer; son Arnold was a well-known child psychologist; and grandson Gerhard a respected federal judge. Their journey began in small towns along the Mississippi River.

The Photographer

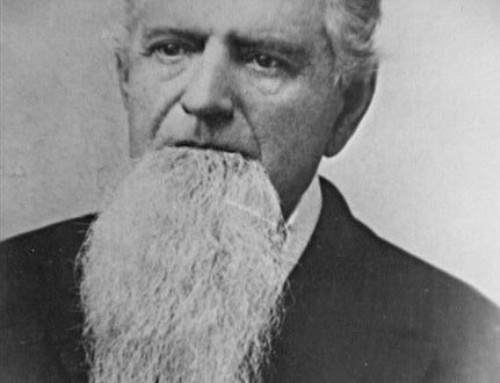

Gerhard (circa 1846-1906) settled in Minnesota (two of his brothers were already living there) but soon enlisted in the Army during the Civil War, serving with Brackett’s Battalion in the West. After the war, he returned to Minnesota, to Reads Landing, and worked in a saloon for a few years during the logging boom years. In 1873, he opened his first photography studio, moving across the Mississippi River to Alma, Wisconsin, three years later. In 1879, he married Christine Giesen, a teacher; they would have five children.

Gerhard captured the life and people of Alma in thousands of photographs. He had a gift for capturing moments that showed the spirit of life in a Mississippi River town, taking photos of folks from all walks of life in Alma, but especially of children. One of the more remarkable Gesell prints hangs in the lobby of the Buffalo County Courthouse in Alma. Pioneers of Buffalo Co., Wis. is a composite photo created from 156 individual portraits of people who settled in the area prior to 1857.

You can browse a collection of his photographs online at the Wisconsin Historical Society or look at prints in the Alma Area Museum. Gerhard died in 1906, three years after closing his studio.

The Child Psychologist

The Gesell’s oldest child, Arnold (1880-1961) earned a PhD in 1906 from Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts. At the time Arnold was enrolled, the President of the school was G. Stanley Hall, one of the founders of American psychology. Not one to rest on his laurels, Arnold went on to earn an MD from Yale University in 1915. Like his father, he married a teacher, Beatrice Chandler; he and Beatrice met when they were on the faculty of the Los Angeles State Normal School. They would have a son and a daughter.

Arnold specialized in child development and was tremendously influential in the field. He was a pioneer in identifying age-appropriate signs that signaled developmental progress and also developed new research techniques that advanced the science of child development.

Arnold Gesell also waded hip-deep in controversy when he embraced eugenics early in his career, an increasingly popular theory at the time that advocated selective breeding of humans in order to increase the prevalence of desirable traits over undesirable ones. Proponents of eugenics believed that genes were far more important in human development than environmental factors.

Many eugenicists also believed that white people were genetically superior to everyone else, and that economic success also indicated superior genes. Eugenicists, for example, promoted the belief that poor people had less desirable genes and therefore shouldn’t be allowed to have children. In fact, many low-income people were sterilized without their consent in the early 20th century. In Gesell’s native Wisconsin, the legislature passed a law in 1913 that permitted involuntary sterilization of the developmentally disabled in institutions and inmates in the state’s prisons.

In 1913, Arnold wrote an article called “The Village of a Thousand Souls” in which he detailed rates of undesirable traits such as alcoholism, mental illness, and feeble-mindedness among residents of a small town, arguing that selective breeding could reduce these undesirable characteristics. Although the community was not named, it was obvious that the people whose shortcomings he described were from his hometown. The folks back in Alma were not enthusiastic about the publicity.

Over time, as the science of eugenics became discredited (thanks in part to the Nazi’s embrace of the concept), Gesell’s views evolved away from the controversial theory and toward a view that recognized a more subtle interaction between nature and nurture. Arnold went on to a distinguished and influential career, the highest profile child development specialist until Dr. Spock. He served on the faculty of Yale University for 37 years, founding the Yale Child Study Center. After he retired, he ran the Gesell Institute of Child Development in New Haven, Connecticut.

The Judge

Arnold’s son, Gerhard (1911-1993), also could not escape controversy, although he wasn’t usually the cause of it. He graduated from Yale Law School in 1935 and landed a job at the Securities and Exchange Commission right after it was created. He led major investigations of Wall Street and of the insurance industry, then joined a private law firm where he specialized in anti-trust cases, even arguing cases before the US Supreme Court.

In 1967, President Johnson appointed Arnold to the federal judiciary in Washington, DC. Throughout his career, he used his position on the court to take a strong stand against abuses of power. He was the presiding judge for a number of high-profile cases related to Watergate, the Pentagon Papers, and the Iran-contra scandal. In the 1971 Pentagon Papers case, he was the only judge (of 29 involved in the case) who refused to issue an injunction to stop the New York Times from publishing the infamous documents, writing:

It should be obvious that the interests of the Government are inseparable from the interests of the public. These are one and the same, and the public interest makes an instant plea for publication.

In 1986, he laid out his views on democracy to a group of 98 newly minted US citizens, advising them:

You are now part of a great experiment in government…Don’t be willing to leave government to others. Participate…Demand competence in your leaders. Seek out the good, shun the bad. Vote. Work. Help others. Be useful. Obey the law. Speak out against intolerance. Get involved. Use your minds, not your fists. Your voice will be heard.

Judge Gesell was married to Marion Pike for 50 years. They had a son and a daughter, who are no doubt continuing the family’s tradition of changing the world.

©Dean Klinkenberg, 2019