Introduction

Cahokia is the exception to the industry-dominated towns in St. Louis’ Metro East. Established in 1699 by French-Canadian missionaries, Cahokia was the first European settlement on the Mississippi River—it is older than New Orleans and St. Louis—it has just had a different trajectory since its founding.

Visitor Information

Your best bet for information on visiting the historic sites in and around Cahokia is to stop in to the Cahokia Courthouse State Historic Site (107 Elm St.; 618.332.1782).

History

In May 1699, Cahokia sprang to life as the Mission of the Holy Family of the Tamaroa, established by priests from the Seminary of Foreign Missions. The territory where the mission was founded was home to about 2,000 Native Americans, most of whom were closely-related Tamaroa and Cahokia Indians, but also a few members of other tribes, like the Metchigamia and Peoria (all four of whom were part of the Illini Confederacy). They lived in an ecologically rich region that had probably been continuously inhabited for millennia.

Cahokia grew very slowly at first. In 1720, the Jesuit missionary, Pierre Francois Xavier de Charlevoix spent a night in Cahokia, observing:

It is situated on a little River, which comes from the East, and which has no Water but in the Spring Season; so that we were forced to walk a good half League to the Cabins. I was surprised that they had chosen such an inconvenient Situation, as they might have found a much better [sic]; but they told me that the Mississippi washed the Foot of the Village when it was built, and that in three Years it had lost half a League of Ground, and that they were thinking of looking out for another Settlement.

The first known census was completed in 1723, which counted just 12 residents, not including the priests or the enslaved Africans or Indians owned by the priests. In contrast, the two French settlements further downriver were much larger: Kaskaskia had 196 residents, while Fort de Chartres had 126. Still, there wasn’t much of a European presence nearby, so Cahokia grew into an important frontier outpost, at least until eclipsed by St. Louis after it was founded in 1764.

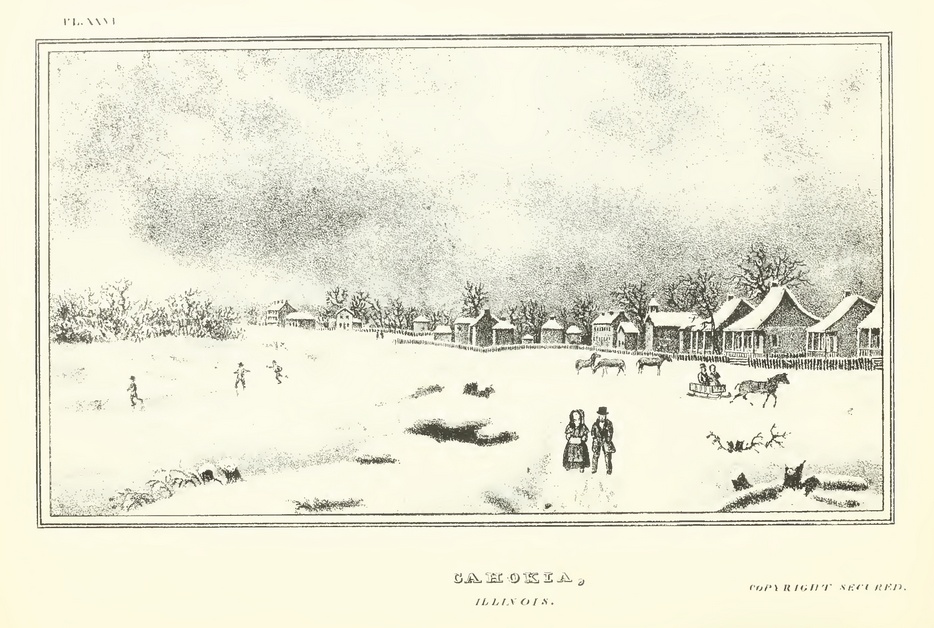

Cahokia was laid out like other French colonial villages of the era. The residential area was divided into 300-foot blocks, each one broken into four lots. Each lot was surrounded by a fence and had, besides a house, a couple of outbuildings, a garden, and a well.

Farm land was allocated outside of the town in a common field, which wasn’t land owned communally, as the name implies. Each person owned and farmed a section of the field, which was typically about 200 feet wide but as long as three or four miles. The entire common field was surrounded by a fence that every owner helped maintain. After crops were harvested, the community moved domesticated animals (cows and pigs, mostly) into the fields where they wintered.

For those early French habitants, blue was apparently a popular color choice for clothing; men and women typically wore blue handkerchiefs on their heads. Men wore pants made of coarse blue cloth in the summer (but buckskin pants in winter). Cahokians were observant Catholics but when mass was over, they liked to have fun. Dances were a regular feature of Sunday entertainment; the whole community usually gathered in a ballroom to dance the evening away.

Like other French colonial villages in the area (Sainte Genevieve and Prairie du Rocher), Cahokians carried on an old New Year’s Eve tradition.

The ancient innocent custom was for the young men about the last of the year to disguise themselves in old clothes, as beggars, and go around the village in the several houses, where they knew they would be well received. They enter the houses dancing what they call the Gionie, which is a friendly request for them to meet and have a ball to dance away the old year.

A census in 1752 counted 136 residents, which included 24 enslaved blacks and 23 enslaved Indians (but still didn’t include the clerics). The villagers had a pretty good life at that point. When Jesuit Father Vivier visited in November 1750, he noted:

…maize—which in France is called Turkish corn—grows marvelously; it yields more than a thousandfold; it is the food the domestic cattle, of the slaves, and of most of the natives of the country, who eat it as a treat. The country produces three times as much food as can be consumed by it. Nowhere is game more abundant; from mid-October to the end of March the people live almost entirely on game, especially on the wild ox [buffalo] and deer.

The British took control of the Illinois Country after defeating France in wars in Europe and North America in the 1760s. Some residents didn’t want to live under British rule and moved across the Mississippi to St. Louis and Sainte Genevieve. Even the French clerics sold all their property, including their land and a dozen enslaved workers. The remaining residents weren’t pleased about the sale of the church and tried to block it. They were ultimately successful, but not until 1786, when the sale was voided and the church re-established.

The British weren’t too interested in Cahokia, and the quality of life deteriorated for the people who stayed behind. In 1779, Captain Philip Pittman observed:

The inhabitants of this place depend more on hunting, and their Indian trade, than on agriculture, as they scarcely raise corn enough for their own consumption: they have a great deal of poultry and good stocks of horned cattle… What is called the fort is a small house standing in the center of the village; it differs in nothing from the other houses except in being one of the poorest; it was formerly enclosed with high pallisades, but these were torn down and burnt. Indeed a fort at this place could be of but little use.

On July 6, 1778, Joseph Bowman led a unit of the Virginia militia into Cahokia to occupy it for the United States in its war for independence from Britain. The French residents of Cahokia offered no resistance, and some, in fact, volunteered for military campaigns against the British. At the time of the American takeover, Cahokia had around 450 residents and would top 700 a decade later. The village served as the seat of St. Clair County from 1795 to 1814, at which time the county government was moved to Belleville.

The old French traditions faded away in the 19th century. In 1841, the common fields were surveyed and leased out; the village used the money to build a school. The village in the 1840s had about seventy houses, a courthouse, a Catholic school, three taverns, a few groceries, and a general store. A major flood in 1844 damaged most of the village, with ten feet or more of water flowing through town.

By 1880, the population was around 300 people, a quarter of whom were African American. Even though the village was small, it still maintained segregated schools. The school for white students was a brick structure that cost $5,000 to build; the school for African American children was a frame building that cost $800. The village didn’t have much industry, but there were a couple of coal mines in the bluffs near town.

Oliver Parks founded an aviation school in Cahokia in 1927 and called Parks College (of course). He donated the school to Saint Louis University in 1946, which kept the program in Cahokia for 46 years. In 1992, the university moved the programs to its main campus, where they still operate the Parks College of Engineering and Aviation.

Parks College wasn’t the only aviation-related business in Cahokia. In 1929, a consortium of businesses and a private investor opened Curtiss-Steinberg Airport. Those founders included the Curtiss Wright Company (they built planes and aircraft engines), St. Louis financier Mark Steinberg, the Transcontinental Air Transport Service (which later became TWA), and the Pennsylvania Railroad Company.

Oliver Parks took over management of the airport in the mid-1930s; it was a busy place with commercial traffic and test flights for experimental aircraft. During World War II, the college and airport became one of the primary training sites for pilots in the US Army Air Forces (USAAF). One-sixth of USAAF pilots—24,000 men—completed their training in Cahokia.

Demand declined in the 1950s as Lambert Airport in St. Louis grew into the major hub for the region. Curtiss-Parks Airport closed in 1959 and Oliver Parks turned his attention to developing subdivisions in the area. As Lambert got busier, however, the region needed more runways, so Bi-State Development bought the old airport in 1964 and reopened it the next year as Bi-State Parks Airport. Traffic has grown steadily since then. Today the airport serves a lot of corporate clients, as well as emergency medical flights, including planes that deliver organs to transplant centers. The name has changed a couple of more times; now it is known as St. Louis Downtown Airport.

In 1950, even with the airport and Parks College, Cahokia was a small town with only 794 residents, but by 1960 the population had exploded to nearly 16,000, thanks to annexation, the availability of affordable tract housing, and highways to reach them. It is largely a bedroom community today, but one that has preserved some impressive architectural links to its past.

Exploring the Area

The Village of Cahokia has some outstanding buildings from the French colonial period built in the style called poteaux-sur-sol (post-on-sill), in which logs are aligned vertically on a horizontal beam. The most spectacular example is the Church of the Holy Family (East 1st and Church Streets; 618.337.4548). The congregation dates to 1699. The log church dates to 1799 and is constructed of timbers of native black walnut; the gaps between the logs were filled with stone rubble and lime infill called pierrotage. Inside the church, look up at the the 85-foot-long timber that helps support the ceiling; it was cut from a single tree. The church is open for tours during the summer; at other times, you might be able to schedule a visit by calling ahead.

The building next to Holy Family Church is the Jarrot Mansion (124 E. First St.; 618.332.1782). It was built in 1810 in what some have called the Frontier Federal style; it is the oldest brick structure in Illinois. Nicholas Jarrot, a native of France, moved to Cahokia in 1794. While he did OK as an Indian trader and running a general store in town, he got rich from real estate investments. The interior of the house has been painstakingly restored to its original appearance. During restoration, several horse heads were discovered hidden inside walls. No one knows why there were there. Call ahead for information on when the house is open for tours.

Cahokia Courthouse State Historic Site (107 Elm St.; 618.332.1782) is another example of the post-on-sill construction style. Built originally as a private residence around 1737, the building served as a courthouse for part of the Northwest Territory from 1790 to 1814. The current structure with its double-pitched roof is a faithful restoration, although few original materials remain.

**Cahokia is covered in Road Tripping Along the Great River Road, Vol. 1. Click the link above for more. Disclosure: This website may be compensated for linking to other sites or for sales of products we link to.

Community-supported writing

If you like the content at the Mississippi Valley Traveler, please consider showing your support by making a one-time contribution or by subscribing through Patreon. Book sales don’t fully cover my costs, and I don’t have deep corporate pockets bankrolling my work. I’m a freelance writer bringing you stories about life along the Mississippi River. I need your help to keep this going. Every dollar you contribute makes it possible for me to continue sharing stories about America’s Greatest River!

Cahokia Photographs

©Dean Klinkenberg, 2024, 2021, 2018,2013,2011