I used a big chunk of my unplanned down time in 2020 to read books and articles about the history of Native Americans along the Mississippi Valley. Before I started this reading binge, I considered myself pretty well informed about indigenous communities along the Mississippi. It didn’t take long for me to realize, though, that I knew a lot less than I thought I did. One of the unfortunate realities of living in the US is that our history classes and books gloss over the extensive and complex history of the people who lived in the Americas when Europeans invaded. If you want to learn about that history, you have to go out of your way to study it.

I’m not going to summarize that entire history, but let’s just say that people have lived along the Mississippi River for at least 10,000 years and many of the cultures along the river flourished for centuries. The Mississippian culture that began around St. Louis (and built the great city we now call Cahokia), ignited a dramatic cultural transformation that spread across centuries and throughout much of North America.

Another insight from all that reading is that I realized there are many sites not far from my home in St. Louis that preserve aspects of Native American history, and many of them date to around the time Mississippian culture blossomed. In June, I visited four of these sites, three in Arkansas and one in eastern Oklahoma. They represent a pretty good cross-section of time periods, ranging from around 650 CE through the first years of contact with Europeans.

Below is a brief introduction to these sites, arranged in chronological order from the earliest to the most recent. All of these sites are open to the public, but it’s a good idea to call ahead to verify their hours.

TIP: Visiting these sites will be more rewarding if you have the chance to read some of their history before you get there. The museums at each place have pretty good exhibits, but they don’t all go into much detail.

Toltec Mounds Archeological State Park

Time Period: 650 to 1050 CE

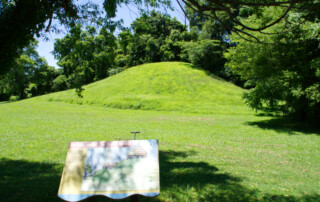

Misnamed in the 19th century, the Toltec Mounds site wasn’t built by the Toltec people of Mesoamerica but rather by a society archaeologists call Plum Bayou. They flourished in the area along Mound Lake, a relic meander of the Arkansas River, an area that provided a wealth of natural resources. The area was lightly populated in its later years, probably serving as a ceremonial or religious center; most people in the area lived in villages nearby.

At one time, a mile-long earthen embankment wrapped around the site and its eighteen mounds, a structure that set off the interior as sacred space. The mounds were built in specific places that aligned with solar and celestial events. A person standing on Mound A on the morning of the summer solstice could watch the sun rise over Mound B. Standing on Mound A on the morning of the equinoxes, that same person could see the sun rise over Mound H. The mounds also aligned with sunsets. From Mound H, a person could watch the sun set over Mound B on the summer solstice and over Mound A on the equinoxes. While the mounds and their alignments were quite effective at marking time, they probably were built more as earthly analogues of the culture’s views about life and the afterlife than simply as calendars.

The Plum Bayou culture seems to have declined around the time that Cahokia grew into a major city. The presence of characteristically Plum Bayou pottery at Cahokia (as well as a couple of other cultural markers) often tantalizing hints at the possibility that some people from the Plum Bayou culture had a hand in the creation of the great Native American city on the Mississippi.

Toltec Mounds Archeological State Park

490 Toltec Mounds Road

Scott, Arkansas 72142 (just outside of Little Rock)

(501) 961-9442

Spiro Mounds Archaeological Center (Oklahoma)

Time Period: 850 to 1450 CE

Once the home of a thriving village of people who made good use of their location along the Arkansas River to broker trade between the Mississippian societies to the east and plains cultures to the north and west. We have only a limited understanding of them. For example, most scholars have posited that the people of Spiro were Caddoan speakers, but some recent scholars have suggested that they could have been Tunican speakers.

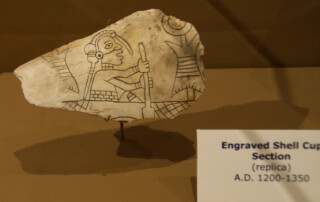

The area that is now the historic site eventually evolved into the center of ceremonial life as most of the community moved into satellite villages. This ceremonial center had twelve mounds (many built to align with solar events) and a few homes for religious and political leaders. Spiro peaked as a trade center between 1100 and 1350, and what a peak it was. From people in the east they acquired copper, lead, shells from the Gulf, and Appalachian mica. From people in the west, they got bison hides, tallow, dried meat, salt, and Osage wood (which was prized for bows). They weren’t just traders, though. Their own craftspeople made valuable pipes from sandstone, engraved shells, and embossed copper plates.

As you might guess, they accumulated an impressive collection of goods from across North America. Many of those goods ended up in the burial chambers of their leaders. One mound in particular, what is known now as Craig Mound, was so rich with artifacts that some people compared it to King Tut’s tomb. Much of what was in the mound was looted during the 1930s, though, when the land was leased to a group of artifact scavengers known as the Pocolo Mining Company. They sold many items and damaged even more. Based on reports from the time, we know that Craig Mound contained a mind-boggling collection of items, including rare artifacts like fabrics that survived because they were protected over the centuries by the abundance of copper and shells buried in the mound. Most of that was lost in the 1930s.

At the historic site today, visitors can walk the grounds among the remnants of the mounds and tour a reconstructed winter home from Mississippian era. The museum has some nice displays and even though most of the artifacts are replicas, they give a good sense of their craftmanship and artistic talents.

The people of Spiro Mounds may have eventually abandoned this place, but they didn’t vanish. They moved on to other places to live and probably intermarried with other communities. The people of Spiro Mounds may be the ancestors of today’s Caddo Nation, Wichita people, and related groups.

Spiro Mounds Archaeological Center

18154 First Street

Spiro, OK 74959

(918) 962-2062

Parkin Archeological State Park

Time Period: 1350 to 1600 CE

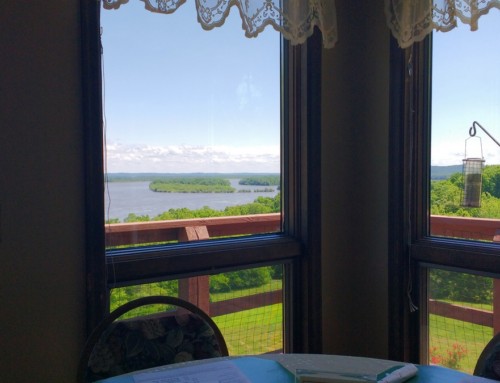

The Parkin Site was home to a Mississippian culture that flourished after the decline of Cahokia and through the early years of European contact. It was probably the administrative center of the province that de Soto’s scribes called Casqui, a place that the Spanish army invaded in 1542. Built at the confluence of the St. Francis and Tyronza Rivers, the village originally was surrounded by a moat on three sides (and the St. Francis River on the fourth), as well as a wall.

Casqui consisted of multiple walled villages in which perhaps 20,000 people lived. The villages formed a nearly-continuous line along the higher ground near the rivers, built atop the natural levees along river channels so they rarely flooded. The area was rich with wildlife, and the people of Casqui grew crops such as corn and squash. They were also adept manager of the adjacent forests, which they tended carefully to ensure that fruit and nut trees would thrive. That’s probably why the Spanish army reported finding (and looting) an abundance of pecans in storage at Casqui.

Today’s state park preserves the site of the capital and includes a museum and a paved walking trail. The site has a good museum that displays objects from the period, including human head effigy pots and a couple of artifacts from the Spanish army uncovered at the site. The walking path climbs over the old moat and around a couple of mounds and includes an overlook of the St. Francis River.

Parkin Archeological State Park

60 State Hwy 184

Parkin, Arkansas 72373

(870) 755-2500

Hampson Archeological Museum State Park

Time Period: 1400 to 1600 CE

Nodena is a term archaeologists use to identify a collection of late Mississippi people who lived in the Mississippi River floodplain in northeast Arkansas and southeast Missouri. There are 21 village sites attributed to the Nodena phase, although not all of them were occupied at the same time. In 1542, de Soto’s army attacked some of these villages, which his scribes identified as a province headed by a man known as Pacaha.

One of these villages, the upper Nodena site, was built on a natural levee next to an old channel of the Mississippi that still had water in it when the village was occupied. It was home to upwards of 1,500 residents. This site is located on Hampson plantation, whose owner, a better-than-average amateur archaeologist, James Hampson carefully excavated parts of the site in the early 20th century and established a museum to exhibit his findings. The museum is located in Wilson, Arkansas, several miles from the village site, which is not open to the public.

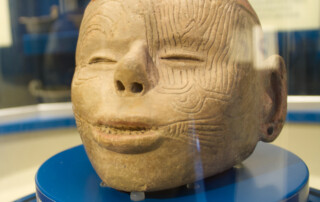

While the number of objects in the museum is modest, they are beautiful and offer a tantalizing peek inside the cultural life of the people who lived in this area centuries ago. Pots dominate, many fully intact and others pieced back together. One in particular–a striking image of a human head–will leave a lasting impression.

Hampson Archeological Museum State Park

33 Park Avenue

Wilson, AR 72395

(870) 655-8622