The north side of downtown Mankato is a monument to modern engineering and 20th century city planning. A concrete wall separates the city from the Minnesota River; Riverfront Drive cuts a five-lane swath for cars to efficiently and quickly pass along. A modern public library sits next to an expansive parking lot. Tucked in between the road and the flood wall, just below an overpass, there’s a small grassy area with spruce trees that hide the flood wall and mature deciduous trees along the (mostly unused) sidewalk.

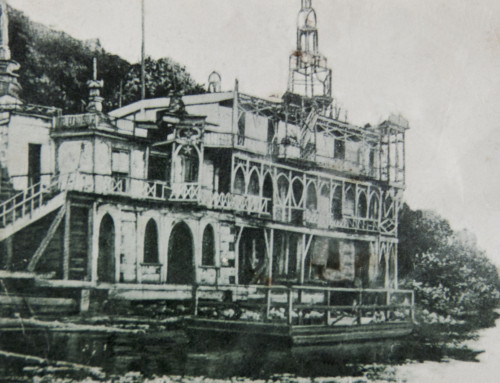

This is Reconciliation Park, a modest effort to pay homage to one tragic event in a series of tragic events 150 years ago that profoundly changed the fortunes of so many people. One hundred and fifty years ago today on this site, 4,000 people crowded into the square and atop the surrounding rooftops of the small Minnesota community to watch the hanging of 38 Santee Dakota men. Like much of the history of the Dakota Conflict of 1862, the old square has been paved over and forgotten.

The immediate causes of the Dakota Conflict were essentially the failure of the US government to live up to treaty obligations and the corruption and greed of a handful of traders and Indian agents. However, the events of the conflict were part of a broader pattern of doing whatever was necessary to push aside, if not eliminate outright, Native American cultures. For most people in the 19th century—and many today—Native American cultures and people were innately inferior to Europeans. Indians were supposed to become like Europeans, or die.

To some, the actions of the Santee Dakota were the acts of brutal savages wreaking havoc on the four –year old State of Minnesota. To others, the Santee Dakota were patriots making one last effort to protect their homeland and culture.

Small bands of Dakota warriors, almost certainly acting without the approval of Little Crow and other chiefs, killed 400 to 500 settlers—men, women, and children—but virtually all of the accounts of brutality and mutilations attributed to the Dakota were later proven false.

The Dakota, on the other hand, were starving and increasingly desperate, confined to a small portion of their former lands and a lifestyle that was as foreign as flying to a turtle. Denied the ability to live off the land as they had for centuries and deprived of the promised resources to help them transition to a new way of life, some Dakota chose to go out fighting rather than withering away.

The deaths of those settlers were tragic, especially for their families, but villages and towns were rebuilt and thousands more settlers poured into the area. They recovered. The Dakota, however—all Dakota—paid dearly. Roughly a thousand Dakota fought in the conflict, but all 6,300 Santee Dakota were punished. The US cancelled the treaties, seized all their land in Minnesota, and imprisoned nearly two thousand at Fort Snelling where hundreds died in the winter of 1862-63, mostly women and children before forcing them out of the state altogether.

The thirty-eight men who were hanged in Mankato were condemned by military tribunals that valued expediency over justice; some “trials” lasted but a few minutes. Many of the condemned insisted until the end that they had had no role in the killing of settlers. The tribunals initially ordered death for 303 captured Dakota men, but President Lincoln reviewed the records and overturned the death sentences for all but 39 of them. One other prisoner was given a last-minute reprieve. The 38 dead Dakota men were buried in a shallow grave along the Minnesota River but during the night, most of the bodies were stolen for use in medical schools or as trophies.

I’ve read through readers’ comments on some articles about the conflict, something I advise against for any Internet article. Many of the comments included statements like: “Hey, they lost the war. It sucks but when you lose, bad things happen. Get over it.” Or “This article isn’t telling the whole story because you didn’t repeat 27 times that some Dakota killed a lot of settlers. Bad things happened to them, too, but you obviously want to blame white people for everything.” Or “I wasn’t alive when those things happened, so quit trying to blame me for it.” Those are some of the nicer comments.

They all miss the larger point (and a bunch of smaller ones, too, like facts). We all need to move on, but I don’t know how it is possible to do so until we acknowledge all of what actually happened. We have to recognize the injustices that were inflicted on the Dakota people, and those of us who are not Native American, also must acknowledge that we benefited from the expulsion and near extermination of the Dakota and other Native Americans. And, no, this isn’t about “white guilt” or reparations. It’s about rejecting injustice, whether it happened today or yesterday, and beginning a conversation about how we can all begin to move forward.

If you want to learn more about the 1862 Dakota Conflict, here are some resources:

Hear a good podcast about the Dakota Conflict on This American Life that aired in November 2012.

Read a good summary of the courtroom proceedings against the Dakota Indians and a reporter’s account of the hangings printed in the New York Times in 1862.

© Dean Klinkenberg, 2012