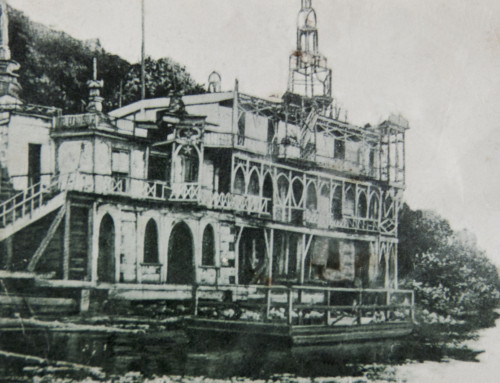

The old highway snakes its way through Fort Madison on a course that roughly follows the Mississippi River. As you drive through town from the north, you pass the state penitentiary with its imposing limestone walls, the 1927-era double-decker swing bridge, and the Mississippi River and riverfront with a rebuilt frontier fort and the century-old rail depots. Just north of the riverfront (the Mississippi runs more or less from east to west here), you’ll find a modest downtown area with a few architectural gems and a few vacant storefronts. Further down, the road passes through a neighborhood that rose and fell with the Santa Fe Railroad, then exits town via a small section of strip malls and new hotels as you get closer to the highway. The views are at times scenic, intriguing, and disheartening. But, this is a place that has been built over generations, with good times and bad times that are both obvious as you pass through.

Until last November, if you were driving on US Highway 61 you had to follow this route through the heart of Fort Madison. With a new bypass open for business the last few months, drivers don’t have to turn off the cruise control at Fort Madison. State officials trotted out the standard benefits of the new bypass (speed and safety). State Senator Gene Fraise even suggested the utility of the new bypass as an evacuation route. It’s comforting to know that the next time a hurricane rolls up the Mississippi to Iowa, people will be able to get away from Fort Madison quickly.

The drive through town feels like it takes forever, but, for the record, on a recent trip it took me exactly 14 minutes to get through Fort Madison on the old route. The bypass is 9 ½ miles long, so you can probably zip down that in nine minutes. The $25 million bypass therefore saves all of five minutes of travel time. In case you were wondering, the total budget for Fort Madison in the current fiscal year is about $21 million.

The completion of this bypass moves Iowa’s portion of US 61 closer to being the efficient superhighway that engineers dream of, with a speed limit of 65 and the inconvenience of going slower than that reduced to the sections of strip mall homogeneity along the edges of Burlington and Muscatine. Maybe the state should build a bypass around those areas, too.

Folks in Fort Madison seem wary but optimistic about the bypass, concerned about the economic impact, especially downtown, but hopeful that fewer semis will be rolling down city streets. Most of the land around the bypass is outside the city limits, so any new development will not mean more revenue for Fort Madison unless it annexes those areas. In fact, if the bypass triggers annexation or if new development spreads the city out even more, Fort Madison may be a net loser. It will acquire more infrastructure that it won’t be able to maintain, even as existing infrastructure in established parts of town crumbles.

The studies I’ve read suggest that the economic benefits of bypasses are essentially a wash. Businesses on the old route—gas stations and motels, for example—will make less money. Others may see an increase, especially if they are close to the bypass. Even if that proves to be true, what saddens me the most is the easy way a community slips from our consciousness after a bypass is built.

When you have to drive through a town on the way to someplace, you are forced to notice that it exists, maybe you’ll even look around and note what the place looks like or which heroes it has honored. With a bypass, you don’t have a chance to see any of those things.

The redesigned highway makes it a lot easier for drivers to bypass Fort Madison literally and metaphorically. If you are on a long drive, you won’t notice anything about a city that is merely a name on a highway exit sign.

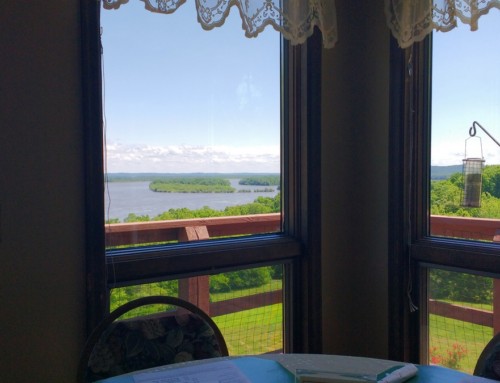

I hope travelers will skip the bypass and follow Business 61 through town, even if they have no specific sights they want to see. You may decide to visit the Sheaffer Pen Museum, eat comfort food at the 1940s-era Fort Diner, get something sweet at the renowned Ivy Bake Shoppe, drink a locally-brewed beer at the Lost Duck Brewing Company, or just walk along the riverfront.

Meanwhile, for everyone driving the new bypass, the landscape will look familiar. The open landscape of today will gradually sprout convenience stores and fast food joints at the off ramps. Instead of passing through a city with its own unique characteristics, you’ll experience more of the homogenized landscape that already dominates our highways, one more route with places that look like every other place in one long, unrelenting chain of conformity.

Maybe this is just so much sentimental whining. It wouldn’t be the first time for me. After all, we’ve already built thousands of these bypasses; I was hoping that Fort Madison might somehow escape that fate.

For me, seeing everything—even being forced to see it all—is an important part of understanding who we are and where we came from. We get a distorted view of the world by driving on highways with the same footprint that present a mono-cultural experience. Your Happy Meal doesn’t come with a side of the beauty and despair that co-exist in our communities, and a personal pan pizza won’t show you how the middle part of the US developed because of the Mississippi River.

So skip the bypass. Take the drive into town, look around a bit. Notice that Fort Madison exists.

© Dean Klinkenberg, 2012