Dred and Harriet Scott are among the most famous people in American history, but what do we know about who they were and what life was like for them and their family? Given their roles at the center of one of the most critical legal battles in US history, it’s surprising we don’t know more. Then again, given their status as enslaved people in the US, it’s surprising we know as much as we do.

Here’s the basic outline of their lives. Dred Scott was born enslaved in Southampton County, Virginia, between 1795 and 1809 as the property of Peter and Elizabeth (Taylor) Blow. Harriet Robinson was born around 1820, but we know almost nothing about her early life.

Dred and Harriet met in the mid-1830s at Fort Snelling (near today’s Minneapolis) when it was part of the Wisconsin Territory. (Minnesota Territory wasn’t created until 1849.) At that time, Dred was owned by the post surgeon, Dr. John Emerson, while Harriet was owned by Major Lawrence Taliaferro, the Indian agent at the fort.

In 1836 or 1837, Taliaferro married the couple in a ceremony at the fort. Dred and Harriet had two sons who died young and two daughters who lived into adulthood. Eliza Scott was born in October 1838 on the Mississippi River aboard the steamboat Gypsy. She married Joshua Wilson Madison. Lizzie was born in 1846 or 1847, probably near St. Louis. It’s likely that she never married.

Dred Scott died in St. Louis on September 17, 1858, from tuberculosis; he had been in poor health for years. Harriet died in St. Louis nearly 18 years later, on June 17, 1876. So that’s a rough timeline of the lives of Dred and Harriet Scott and their children, but there’s much more to their story than dates on a genealogy chart.

From the South to the Frontier

In 1818, the Blow family moved to a farm near Huntsville, Alabama, then to Florence, Alabama, three years later. In 1830, the Blows, their attempts at farming a failure, moved to St. Louis with their seven surviving children and six enslaved people, including Dred Scott. Dred got married in St. Louis, but he and wife were separated when she was sold to new owners in Alabama. He ran away to be with her but was caught and beaten before being returned to the Blows.

On June 23, 1832, Peter Blow sold Dred to a US Army surgeon, Dr. John Emerson. Scott would serve primarily as his body servant (something like an involuntary valet for life). About a year after the sale, Emerson was assigned to Fort Armstrong (at today’s Rock Island, Illinois); Scott went with him. Emerson invested in land in Illinois and Iowa, so it’s a pretty good bet that Dred worked on that land at some point. In 1836, Dr. Emerson was transferred to Fort Snelling.

We don’t know much about Harriet Robinson’s early life. It’s possible she was born enslaved to a family named Robinson. Major Taliaferro might have inherited her, or she could have been part of his wife’s (Elizabeth Dillon) dowry when they married. It’s also possible that he bought Harriet at a slave market in St. Louis or Louisville. We just don’t know.

Regardless, Taliaferro became Harriet’s owner in the mid-1820s, and she was at Fort Snelling by the early 1830s. As a servant to Taliaferro at a frontier fort, Harriet would have been present when he hosted guests, like painter George Catlin, as well as Ojibwe and Dakota Indians who visited the fort. Her duties included tending the gardens, managing the household, preparing meals, cleaning, and attending to Mrs. Taliaferro’s needs.

When Harriet Robinson and Dred Scott married at Fort Snelling, Major Taliaferro, as the Justice of the Peace for the area, officiated. Taliaferro then apparently transferred ownership of Harriet to Dr. Emerson. Emerson returned to St. Louis in October 1837, but the Scotts remained at Fort Snelling.

A few months later, Emerson married Eliza Irene Sanford. When Emerson was ordered to Fort Jessup, Texas, he sent for the Scotts to join him, but they were there just a few months. Emerson was transferred back to Fort Snelling in the fall of 1838 (just in time for winter!) and the Scotts soon followed him back there. During the trip upriver, Harriet gave birth to Eliza on the steamboat Gypsy.

The Emersons and Scotts stayed at Fort Snelling until 1840, until Dr. Emerson was transferred to Florida to serve in the Seminole War. When he left Fort Snelling, his wife Eliza and the Scotts moved to rural St. Louis to live with Eliza’s father, Alexander Sanford, a zealous supporter of slavery. The Scotts were probably hired out to work for other people during this time to earn money for the Emersons.

Dr. Emerson came back to St. Louis in August 1842. He bought land and tried to set up a medical practice, but it didn’t go well. He and Irene moved to Davenport intent on developing the land they owned; the Scotts stayed in St. Louis with the Sanfords. It’s unlikely that Dred traveled with Emerson in the last three years of the doctor’s life; Dred’s health wasn’t especially good.

Dr. Emerson apparently intended to make Davenport his permanent home, but he didn’t get the chance. He died on December 29, 1843. Irene moved back to St. Louis.

Irene then rented the Scotts to her brother-in-law, Captain Henry Bainbridge, who took Dred with him to Texas just before the Mexican War. Dred told a reporter that, after getting back from Texas in the spring of 1846, he had asked Mrs. Emerson for permission to buy his family’s freedom. She refused. Instead she (or her father) hired them out to work in a grocery store run by Samuel Russell.

It’s possible that Irene just didn’t know what to do with the Scotts, or that her father wouldn’t let her consider emancipating them. In the midst of this uncertainty, Dred turned to the Blow family for support and advice. The children of Peter Blow, who still lived in St. Louis, had been close to Dred when they were children. Harriet Scott, meanwhile, turned to her community at the Second African Baptist Church (later Central Baptist Church).

Suing for Freedom

The Scotts filed their first freedom lawsuits on April 6, 1846, in a Missouri Circuit Court that was four blocks from their home in St. Louis. Harriet and Dred filed separate suits against Irene Emerson under the previously established legal doctrine of “once free, always free.” Several formerly enslaved people had been granted their freedom by Missouri courts because they had, at some time, lived in territory where slavery was illegal.

The suits were almost certainly filed to protect their daughters. If Harriet and Dred were declared free, then their two minor children would have also been free. If they lost, their daughters were also still enslaved and could be sold to whomever whenever.

Lea VanderVelde makes a strong argument that the suits were probably Harriet’s idea. Her pastor at Second African Baptist Church, the Reverend John R. Anderson, had been born enslaved but managed to purchase his freedom (and his family’s); he later helped other enslaved people to freedom, too. As an eleven-year old enslaved youth, Anderson worked in the print shop of abolitionist Elijah Lovejoy and was in the Alton, Illinois, warehouse the night Lovejoy was murdered. The Scott’s first attorney, Francis Murdoch, was the Alton City Attorney when Lovejoy was killed; he led the prosecution of Lovejoy’s killers. These individuals almost certainly helped Harriet with the details of filing freedom suits.

The Scotts’ lawsuits would drag on for eleven years, during which time they weren’t allowed to leave the city, not even during the terrible cholera epidemic of 1849 when the court had to cancel hearings because too few people showed up to serve on juries.

In February 1848, Alexander Sanford (Irene’s father) died, and his estate was sold off. The next month, Irene Sanford filed a motion requesting that the sheriff take custody of the Scotts. Once they were in the sheriff’s custody, the Scotts probably spent some time in jail, which was the custom at the time, although there are no records confirming it. Most of the time, though, they were hired out to work, primarily for the lawyers representing them. They didn’t get to keep the money they earned, though. Under state law, wages earned while in sheriff’s custody were held in trust until the case was resolved.

After a couple of legal missteps and delays, the Scotts finally got their day in court on January 12, 1850. They won. The jury agreed that the Scotts should be freed, although they didn’t get much time to enjoy it. Irene Sanford Emerson quickly appealed the case to the Missouri Supreme Court. She had some help. Pierre Chouteau, Jr., a prominent member of the city’s founding family and staunch supporter of slavery, helped pay for the legal costs of her appeal.

The Chouteau family was quite familiar with freedom suits. They owned seven members of the Scypion family, who had Natchez Indian ancestry. The Scypions claimed that their family had been illegally enslaved and sued for their freedom. It took 31 years, but they eventually won. Enslaved workers sued the Chouteau family for their freedom at least eleven times: the enslaved workers won six cases, while the Chouteaus won three (the outcome isn’t known for the other two cases). The Chouteau family pushed the Sanfords to fight the Scotts’ freedom suit to the end. The Chouteaus were probably hoping for a court decision that would end the doctrine of “once free, always free.”

The Scotts remained in sheriff’s custody while the Missouri Supreme Court considered the appeal. At that point, in 1850, their suits were combined into Dred’s case. Later in the year, Irene Emerson married Dr. Calvin Chaffee, a vocal abolitionist from Massachusetts. At the time they married, Chaffee apparently didn’t know that his new wife owned an enslaved family suing for their freedom.

On March 22, 1852, the Missouri Supreme Court overturned the jury’s verdict, ruling that that Scotts were still enslaved because they had voluntarily returned to Missouri. Irene Emerson Chaffee quickly filed a motion to end sheriff’s custody, but Judge Alexander Hamilton denied the motion. It’s likely that Irene saw a window of opportunity to sell the Scotts and be done with the Scotts, but everyone involved soon agreed to delay the Scotts’ release from sheriff’s custody as further legal appeals were imminent.

Going Federal

After the decision by the Missouri Supreme Court, the Scotts sent their daughters into hiding. They were probably afraid that Irene would sell them, which she still had the legal right to do. The girls were probably in hiding from 1852 to 1856, although there’s no record of where they went or just how long they were gone. The Scotts’ lawyers filed a federal suit in November 1853 against John Sanford, Irene’s brother, on the belief that ownership of the Scotts had been transferred to him from Irene when she moved to Massachusetts.

The Blow family had been helping the Scotts up to that point, but a federal case would require someone with more with experience. They connected the Scotts to Roswell Field, a prominent attorney with St. Louis ties, who agreed to represent them pro bono.

In 1854, the federal court ruled in favor of Emerson, but the decision was quickly appealed to the US Supreme Court. Field convinced Montgomery Blair to argue the case before the highest court, believing that Blair’s extensive litigation experience would be valuable. Blair also agreed to represent the Scotts pro bono. Gamaliel Bailey, who edited an abolitionist paper National Era, helped raise money to cover court costs.

The Supreme Court heard arguments on February 11, 1856, but didn’t issue their decision until more than a year later. During the wait, Dred Scott nearly died from tuberculosis. On March 6, 1857, the Court released its infamous decision, ruling that persons of African descent were not US citizens, nullifying the Missouri Compromise, and prohibiting Congress from banning slavery in new territories.

Irene’s lawyer filed a claim to collect the back wages earned by the Scotts while they were in sheriff’s custody, about $750 over several years. (There’s no record of what happened to that money.) Besides the lost income, Dred Scott said he had spent about $500 out of his own pocket to keep the cases active. That $1,250 in lost wages and expenses translates into nearly $40,000 in 2019 dollars.

The financial losses were bad enough, but the Scotts must have been emotionally devastated, too, as the decision meant their entire family was still enslaved. The resolution of the legal battles, though, ultimately created a path to freedom for them.

Free At Last

After the Supreme Court decision, the national media uncovered Representative Calvin Chaffee’s role in the Scotts’ life. The Republican congressman and staunch abolitionist was embarrassed, vehemently denying that he knew his wife owned the Scotts. It’s possible that Irene never told him. For the federal lawsuit, after all, the Scott’s had sued her brother, John Sanford. Before that time, the lawsuit had been a personal matter that hadn’t attracted much attention.

When John Sanford died two months after the Supreme Court decision, Irene Sanford Chaffee was the undisputed owner of the Scotts. Calvin Chaffee wanted Irene to move quickly to free the Scotts, but emancipating enslaved people was a complicated process in Missouri. First, the owner had to be a Missouri resident, which the Chaffees were not. On May 13, 1857, the Chaffees fixed that problem when they signed a quit claim deed transferring ownership of the Scotts to Taylor Blow, the son of Dred’s former owner.

On May 26 1857, Taylor Blow filed the quit claim deed with the St. Louis Recorder of Deeds, taking legal ownership of the Scotts. That same day he filed Deeds of Emancipation in the St. Louis Circuit Court for Dred and Harriet Scott and their two daughters. Even that part of the process was difficult. Blow, as their owner, had to make a legal promise to look out for them financially, which he did, by posting a $1,000 bond.

This is the area where the Scotts probably lived in 1857. The image is from Pictorial St. Louis, published in 1875

Even though Chaffee helped ensure that the Scotts were freed, his political career was over. He lost his reelection campaign in 1858 and didn’t serve in elective office again. Still, he deserves some credit for helping the Scotts win their freedom. After all, it’s unlikely that Irene Sanford Chaffee would have freed the Scotts after spending eleven years successfully defending her right to own them.

Dred Scott had an opportunity to make some money after the Supreme Court decision. The case had made the Scotts famous across the country and he was offered $1,000 a month to travel around the North doing public events. He declined. Harriet was afraid someone would try to kidnap him, and Dred just wanted to slip back into obscurity.

Life as Free People

On May 4, 1858, the Scotts received their Free Negro Licenses, guaranteeing that their family would stay intact. At the time of their emancipation, they lived in a St. Louis apartment off an alley behind Carr Street, between 6th and 7th Streets, an area with a dense but confusing street layout that didn’t match city plat maps very well. Dred was a porter, probably at Barnum’s Hotel at 2nd and Walnut Streets, where his primary role was apparently to chat with guests who wanted to meet the famous Dred Scott. Harriet worked as a laundress.

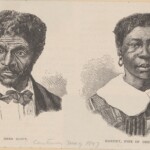

In 1857, the Scotts reluctantly agreed to be interviewed for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. The Scotts made it clear in the article that they just wanted to be left alone. Still, the reporter convinced the Scotts to sit for daguerreotypes at Fitzgibbon’s Gallery in St. Louis. The result is the only known photographs of Dred and Harriet.

Dred Scott didn’t get to enjoy life as a free man for long. He died on September 17, 1858, about sixteen months after Peter Blow freed him. He was initially buried at old Wesleyan Cemetery (at Grand & Laclede, where St. Louis University is today). Blow family descendants paid for the burial. Taylor Blow moved Dred Scott’s remains to Calvary Cemetery in 1867 and had him reburied without a marker. There’s no record of why he was moved, but Blow may have been afraid that Scott’s grave would be vandalized in the aftermath of the Civil War.

Harriet and their daughters stayed in St. Louis through the Civil War, living in the city while it was governed under martial law. Harriet Scott died June 17, 1876. Her faith community, the 8th Street Baptist Church, held a memorial service in her honor. She was buried at Greenwood Cemetery in north St. Louis County. Like Dred, someone helped pay for her burial, probably another member of the Blow family. Also like Dred, there was no marker; Harriet’s gravesite would eventually be forgotten. On November 6, 1999, the Elijah Lovejoy Society placed a cenotaph at Calvary Cemetery for Harriet, because her actual burial site wasn’t known at the time. Seven years later, Ruth Ann Hagar found documentation of Harriet’s burial at Greenwood; a few years after that, a monument was finally placed for her at Greenwood Cemetery.

The Legacy

The Scott daughters went on to lead quite different lives. Eliza, the oldest, married Wilson Madison. They had perhaps seven children, but only two sons survived to adulthood.

Lizzie, on the other hand, who had spent a chunk of her childhood in hiding, spent much of her adulthood in obscurity. She disappeared so well that many people assumed she had died much earlier than she actually did. In fact, she not only outlived her sister and brother-in-law, but at least one nephew, too. Ruth Ann Hager pieced together the last years of Lizzie’s life with the help of Lizzie’s grand-niece, Alma.

In the 1930s, Lizzie lived in a two-room house near St. Louis‘ Union Station. Her only light came from a single kerosene lamp. Heavy drapes covered the windows. She disguised her identity by identifying as a widow named Lizzie Marshall, even though there’s no record that she ever married. Still, she maintained close ties with her family.

After her nephew John Madison died in 1931, Lizzie—then about 85 years old—walked 3 ½ miles back and forth every day for a year to babysit her grand-nephews and grand-nieces. For a while after that, she walked to their house every Sunday to pick up her grand-niece Alma, then rode the streetcar back to her house where Alma stayed until Friday evening.

Years later, Alma remembered Lizzie as tall and slender, usually dressed in dark, full-length skirts. She seemed stern to the young Alma and didn’t talk much, except to John’s widow, Grace. Lizzie continued to work well into her 80s. Three days a week, she cleaned a boarding house, bringing Alma with her, but stopping on the way to buy a piece of pie from a street vendor. Lizzie died on December 19, 1945, at Homer G. Philips Hospital in St. Louis; she was nearly 100 years old.

Dred and Harriet Scott have living descendants to this day, many of whom helped found the Dred Scott Heritage Foundation, an organization that promotes reconciliation through face-to-face meetings between descendants of slave-owning families and the people they enslaved. What a remarkable journey for the Scott family, from suffering under the injustices and brutality of an immoral institution to promoting and embracing forgiveness.

Sources

Arenson, Adam: Freeing Dred Scott, Common Place, Vol. 8(3), April 2008, http://commonplace.online/article/freeing-dred-scott/.

Fehrenbach, Don E.: The Dred Scott Case: Its Significance in American Law and Politics. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978.

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, June 27, 1857.

Hager, Ruth Ann (Abels): Dred & Harriet Scott: Their Family Story. St. Louis County Library. 2010.

VanderVelde, Lea S.: The Dred Scott Case in Context. University of Iowa Legal Studies Research Paper Series; Number 16-03, 263-281, March 2016, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2709161.

VanderVelde, Lea S.: Mrs. Dred Scott: A Life on Slavery’s Frontier. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

VanderVelde, Lea S. & Subramanian, Sandhya: Mrs. Dred Scott. Yale Law Journal, 106(4), 1033-1122, 1997, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2567892.

**Want to know more about the places along the Mississippi River? Check out Road Tripping Along the Great River Road, Vol. 1. Click the link above for more. Disclosure: This website may be compensated for linking to other sites or for sales of products we link to.

Community-supported writing

If you like the content at the Mississippi Valley Traveler, please consider showing your support by making a one-time contribution or by subscribing through Patreon. Book sales don’t fully cover my costs, and I don’t have deep corporate pockets bankrolling my work. I’m a freelance writer bringing you stories about life along the Mississippi River. I need your help to keep this going. Every dollar you contribute makes it possible for me to continue sharing stories about America’s Greatest River!