Visitor Information

Get your questions answered from the folks at the Pike County Chamber of Commerce (217.285.2971).

History

In 1836, Chester Churchill and Bridge Whitten, natives of New York, founded the village of Kinderhook. The village grew along and below a short bluff, an area that once had many American Indian mounds. It grew into a stable small town pretty quickly, with several stores, a blacksmith, a flour mill, a post office, and a couple of churches (Baptist and Methodist Episcopal). By the mid-1840s there were also a couple of Mormon churches nearby.

As Mormons established communities and churches in the area, not everyone was pleased. Three Kinderhook men—Bridge Whitten, Robert Wiley, and Wilburn Fugate—were determined to embarrass the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) by creating a hoax that played on Joseph Smith’s origin story, that he found a set of gold plates that became the basis for a new sacred text called the Book of Mormon.

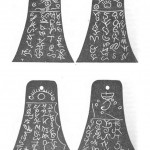

Whitten, a blacksmith, forged six bell-shaped plates from brass, each rather small at four inches long by 1 ¾ inches wide at the top, tapering out to an inch wider at the bottom. The three of them also etched symbols into the plates that looked quite foreign; some folks later called them hieroglyphics. On April 16, 1843 Wiley secretly buried the plates in a burial mound, placing them under a big piece of limestone and adding a few bones and pottery pieces for that extra dramatic touch. That same day, he told the press that he had dreamt for three straight nights that a treasure was buried in that spot. He began to dig, and when he hit limestone about ten feet down, he said he needed more help, so he quit digging. He came back a week later with five extra guys plus two leaders of the LDS Church to witness the extraordinary discovery.

The plates were removed and taken to Nauvoo where Joseph Smith apparently looked them over on May 1. Smith did not personally record his observations or a translation, but his private secretary, William Clayton, made a note that Smith had partially translated them. According Clayton’s note, Smith said the plates recorded the history of the person found with the plates who was “a descendant of Ham through the loins of Pharaoh king of Egypt, and that he received his kingdom from the ruler of heaven and earth.”(1)

The Quincy Whig ran a story about the plates on May 3, reporting that one of the Mormon witnesses “leaped for joy at the discovery, and remarked that it would go to prove the authenticity of the Book of Mormon—which it undoubtedly will.”(2)

The plates were returned to Pike County, their place in Mormon history apparently secure as the three hoaxters moved on. Wiley moved to St. Louis by 1850 for medical school; Whitten moved to Alton; only Fugate stuck around Kinderhook. Wiley kept the plates, later donating them to his medical school for a museum. That museum was ransacked by the Union Army during the Civil War (the founder of the school, Dr. Joseph McDowell, was a Confederate sympathizer) and the plates disappeared.

Meanwhile, officials within the LDS Church firmly supported the authenticity of the plates…for the next 140 years. One of the plates eventually turned up in the collection of the Chicago Historical Society, which verified it was one of the Kinderhook plates but the discovery was ignored for over thirty years. The plate was examined by Welby Ricks, president of the Brigham Young University Archeological Society in the 1960s; he declared the plate authentic. Finally, around 1980, Dr. Stanley Kimball, an expert in Mormon history and a member of the LDS Church, pushed for new studies of the plate that would finally correctly conclude that it was a hoax. In 1981, the LDS Church officially accepted the study’s results and declared the plates a hoax; the LDS Church absolved Joseph Smith of any responsibility for not discovering the hoax by declaring that he simply ignored the plates.

This all could have been cleared up much sooner. In June 1879, Fugate wrote a letter to a friend confessing his role in the whole thing. That friend, James Cobb, lived in Salt Lake City and published the letter so it could be read by Mormons in the area. He wrote:

We read in Pratt’s prophecy that ‘Truth is yet to spring out of the earth.’ We concluded to prove the prophecy by way of a joke. We soon made our plans and executed them. Bridge Whitton cut them out of some pieces of copper; Wiley and I made the hieroglyphics by making impressions on beeswax and filling them with acid and putting it on the plates. When they were finished we put them together with rust made of nitric acid, old iron and lead, and bound them with a piece of hoop iron, covering them completely with the rust.(1)

The LDS Church, however, dismissed the letter as a hoax, because the plates were still missing and none of Fugate’s conspirators were still alive to corroborate his story. It would take another 100 years before the Church would see the light.

Sources

1. Kinderhook plates brought to Joseph Smith appear to be a Nineteenth-century hoax; Stanley B. Kimball

2. Quincy Whig, May 3, 1843; p. 2

Exploring the Area

The post office in Kinderhook is one of the more unique ones you will encounter. The simple building and nearby walls are decorated with jugs, marbles, model T caps, and other salvaged material that is mortared into the structures, much of it contributed by local physician, Dr. P.H. Dechow.

The Kinderhook Historical Society maintains a small museum in a building across the street from the post office. If you wish to visit, call the Pike County Chamber of Commerce for the most current contacts (217.285.2971).

Detour to New Philadelphia

If you’ve got an extra hour or so to spare, take a sidetrip to the site of the former settlement of New Philadelphia, founded by Free Frank McWorter. In 2009 the New Philadelphia site was designated a National Historic Landmark.

Frank was born enslaved in South Carolina in 1777. His mother, Juda, a native of West Africa, was kidnapped and enslaved in America; Frank’s father was probably her master, George McWhorter. McWhorter moved from South Carolina to Kentucky in 1795, which is where Frank met Lucy. They married in 1799 and had four children while they were enslaved.

Living on the sparsely populated frontier, Frank had access to have several opportunities to earn money, chances that were inaccessible to most enslaved people. McWhorter let him hire out his services, in exchange for a big cut of his wages, but that still left Frank with extra money he could pocket for himself. In his off hours, mostly at night, Frank also mined crude niter, which was abundant in the area, and processed it into saltpeter, a key component of gun powder. When the War of 1812 broke out, saltpeter was in high demand, so Frank earned quite a lot of money, but his mining and processing operation remained profitable even after the war ended. In 1817, he used his savings to purchase freedom for Lucy for $800. Two years later, he bought his own freedom for $800 and the two began new lives as free individuals in their home in Pulaski County, Kentucky. In the 1820 US Census, he gave his name to the census taker as “Free Frank.”

After he was free, Frank expanded his mining operations to nearby Danville and also bought some land, but life for free blacks in Kentucky became increasingly difficult in the 1820s. In 1829 he sold his saltpeter operation for $1,000 (well below market value) to buy freedom for his oldest son, Frank Jr., who had escaped to Canada. In the spring of 1831, the family (Frank and Lucy had three living children born after she was freed) moved to Illinois to live on 160 acres that Frank bought from Dr. Galen Elliott.

While Illinois was a free state, it was still a pretty hostile place for free blacks, who had to post a $1,000 bond to settle in the state. Frank and family made the transition as well as they did largely because they were able to buy land before they moved to Illinois. Once in Pike County, the family grew oats, barley, potatoes, flax, and tended several types of livestock.

In the latter part of the 1830s, Frank took steps to solidify his legal claims for himself and his family. In 1836, he petitioned the Illinois General Assembly to approve an official name change; the legislation was guided through the assembly by State Senator William Ross, one of the founders of Atlas. With its approval, Free Frank became Frank McWorter. Three years later, Frank and Lucy were legally married under Illinois law, some 40 years after they initially exchanged their vows while enslaved.

Around the same time, Frank bought another 80 acres adjacent to their land where he platted the village of New Philadelphia in 1836. The village was composed of 144 lots, each 60 feet by 120 feet, organized around Main Street and Broad Street.

From the beginning, New Philadelphia was a racially mixed community. In 1850, the village counted 58 residents, 38% of whom were African American; at that time, less than 1% of the Illinois’ population was African American. The village had a single, integrated school and was an active link on the Underground Railroad. Many people in the immediate area relied on the village for its services (grocery store, blacksmith).

Frank used the proceeds from land sales and from his farm income to buy freedom for more family members, returning to Kentucky multiple times to free his remaining children, a daughter-in-law, and two grandchildren. After Frank died in 1854, the family continued his work. Ultimately, Frank’s efforts freed 16 family members from slavery, costing some $14,000 (over $300,000 in 2015 dollars). Lucy died in 1870; she was just shy of 100 years old.

Frank’s village, New Philadelphia, peaked in the mid-1860s; in 1865 it counted 160 residents, 30% of whom were African American. When the first railroad came through the area, it bypassed New Philadelphia, however, which triggered an exodus of businesses and residents. By 1880, the village had just 87 residents and was officially dissolved in 1885; a few people continued to live on their lots into the 1920s, though.

If you want to visit the town site, it is about 10 miles east of Kinderhook. Take Illinois Highway 106 for 8 miles east to County Road 2 and drive another 2 ½ miles to 306th Lane. The historic site has information panels under a shelter at what would have been Broad and North Streets in New Philadelphia. There’s also a walking path with interpretive markers. If you have an Apple device, you can also download the New Philadelphia app to guide you through the site.

Entertainment and Events

Festivals

Kinderhook is one of the communities that participates in the Pike County Fall Pickin’ Days, a chance to enjoy fall color and support local vendors in small towns as you drive around the countryside. Each community offers something a little different for visitors (October).

**Looking for more places along the Mississippi River? Check out Road Tripping Along the Great River Road, Vol. 1. Click the link above for more. Disclosure: This website may be compensated for linking to other sites or for sales of products we link to.

Where to Sleep

Bed and Breakfast Inn/Moderate and Up

Sprague’s Kinderhook Lodge (22168 State Highway 106; 217.432.1090) has a few bed and breakfast rooms, besides group lodging for retreats and special events that is their primary focus.

Where to Go Next

Heading upriver? Check out Hull.

Heading downriver? Check out New Canton.

Community-supported writing

If you like the content at the Mississippi Valley Traveler, please consider showing your support by making a one-time contribution or by subscribing through Patreon. Book sales don’t fully cover my costs, and I don’t have deep corporate pockets bankrolling my work. I’m a freelance writer bringing you stories about life along the Mississippi River. I need your help to keep this going. Every dollar you contribute makes it possible for me to continue sharing stories about America’s Greatest River!

©Dean Klinkenberg, 2016

Thanks for the comment, Linda, and my condolences on the loss of your father.

Thank you. My father’s hometown was Kinderhook; we buried him there in 2016. He always wanted to go back home. Thanks for your research and detail.