Introduction

After 43 miles of flowing from east to west, the Mississippi takes a sharp turn at Muscatine and resumes its mostly southward trek to the Gulf of Mexico. Muscatine was a busy industrial town for decades and still has its share of manufacturing, but many residents today commute to work in the Quad Cities or Iowa City.

Visitor Information

For current info on the area, contact the Muscatine Convention and Visitors Bureau (215 Sycamore St.; 563.272.2534).

History

The first Europeans began arriving in the late 1820s when Davenport’s namesake, Colonel George Davenport, sent Russell Farnham and two aides to set up a trading post. The first official permanent resident was James Casey, who supplied wood to passing steamboats. He wasn’t here long—he died in 1836— but there’s a big rock on the Muscatine riverfront marking “Casey’s Landing.”

Davenport sold his claim to John Vanata in 1836 and that same year the city’s first plat was finished. The new village was called Newburg but it was soon changed to Bloomington. When Bloomington incorporated as a village in 1839, it had 71 residents and 33 buildings. Those early years were difficult; the winters were long and summer brought diseases like cholera that converted potential permanent residents into former residents.

The village had to change its name again in 1849 because their mail was often delivered to Bloomington, Illinois, an inconvenient 160-mile trip to pick up a letter. That’s when the village became Muscatine. The origin of the name is a mystery. Some think there was an island near the city that the Sauk and Meskwaki called Musquitine, a word that interpreter Antoine LeClaire said didn’t mean a thing. Some also speculated that a group of Mascoutin Indians had lived in the area at one time, although there is no evidence that they were ever there. One other theory is that the name means “burning island,” a reference to the smelly grass that burned every year; LeClarie thought that explanation most plausible.

Sam Clemens lived in Muscatine in summer of 1855, staying with his brother, Orion, and their mother. Orion ran a print shop and owned a share of the Muscatine Journal. Young Sam wrote nine letters while traveling around the US that were published in the Muscatine Journal between 1853 and 1855. The Clemens family lived here when German immigrants were arriving, many of them from Hanover and Hessen. They brought beer with them, a lot of it. In the 1850s, Muscatine had five breweries.

The first major growth spurt was fueled by lumber processing, which took off in the 1860s. The industry began in 1838; many mills were at the sharp bend in the river that is still heavily industrial to this day. Peter and Richard Musser ran one of the more successful factories. They bought an interest in Northwestern timber and partnered with Frederick Weyerhaeuser for a while with the Mississippi River Logging Company. The Musser’s businesses got so big (it also included a sash and door factory) that the south part of town became known as “Musserville.”

Employees of the lumber mills worked 11 hour days for which they got $1.50 for unskilled labor or about $2/day for skilled labor. The lumber mills closed by 1905 but the sash and door plants kept going. The Musser’s sash and door plant survived multiple fires and kept going well into the 1960s. Another company, Huttig Building Products, was founded in Muscatine in 1866 as a lumber yard; it is still going today but as part of HON Industries.

The region’s sandy soil, especially on Muscatine Island, proved fertile ground for growing melons, fruit, and vegetables. The agricultural productivity convinced HJ Heinz to open a canning factory in Muscatine, his first outside of Pittsburgh.

Muscatine resident Alexander Clark, Sr. had a big role in helping to desegregate Iowa’s public schools. Clark moved to Muscatine at age 16, working as a barber and in real estate. His son, Alexander Jr., graduated from the University of Iowa Law School in 1879, the first African American to do so. Alexander Sr. became the second black graduate of the law school five years later. In 1867, Alexander Sr. sued the Muscatine Board of Education when his 12-year old daughter, Susan, was refused admission to an all-white school. The next year, the Iowa Supreme Court decided in his favor; within a few years all of Iowa’s schools were desegregated, nearly 90 years before Brown v. Board of Education did the same thing for the rest of the country. Clark Sr. was appointed ambassador to Liberia by President Benjamin Harrison in 1890, where he died the following year.

In the early 20th century, residents could travel from Muscatine all the way to Clinton (65 miles) on the InterUrban rail line. The Muscatine High Bridge opened 1891. It seems it wasn’t an especially well-built structure. A span collapsed in 1899 and again in 1956. The bridge was finally razed in 1973, but one pylon is still standing in Riverside Park. When the bridge was still around, the toll booth also served as a small convenience store where you could buy lemonade, fireworks, stamps, tobacco, and some sweets.

Pearl Button Manufacturing

While Muscatine had a respectable economy at the end of the 19th century, it hit the big time with its button industry, which boomed due to the abundance of native mussels in the Mississippi. At Muscatine, the river makes a 90 degree turn, creating an area with a slack current perfect for mussel colonies. At the industry’s peak, one-third of the world’s buttons came from Muscatine. The industry also became a major battleground in the struggle for fair wages and decent working conditions.

The man who was most responsible for starting the industry was John Frederick Boepple. Boepple was from Ottensen, Germany where he had worked in the family business, making buttons, of course. High tariffs killed his business, so he left for the United States in 1887 to chase rumors that a large river had a population of mussels that were suitable for button making. He found his mother lode in the Mississippi River and opened the first button factory in 1891. He took great pride in the craftsmanship with which his workers created buttons. He refused to automate—each button was cut by hand—even as the competition grew more fierce and adopted machinery that improved efficiency; his refusal to keep up with the new machinery was eventually his downfall. His business partners forced him out of the factory and Boepple went to work as a shell buyer for other companies.

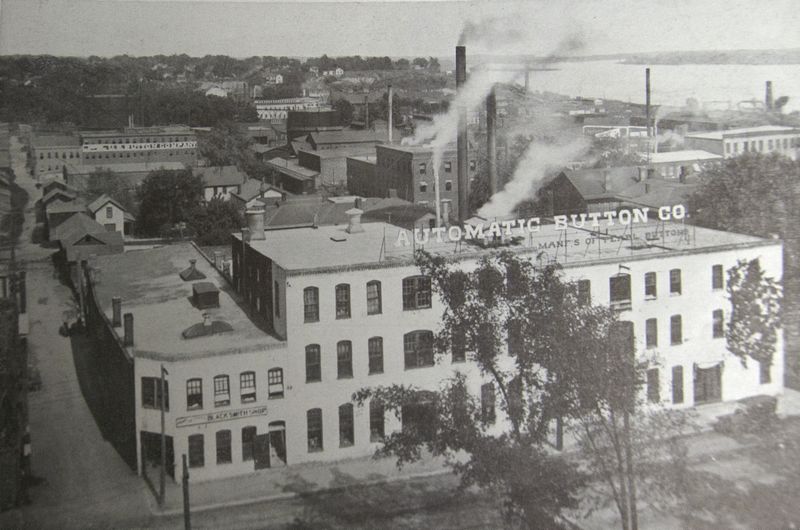

Brothers John and Nicholas Barry were largely responsible for the machinery that sped up the button-making process and made it possible for more and more factories to get into the game. At its peak, the local industry had nearly three dozen factories that produced 1.5 billion buttons a year; half of Muscatine’s working population was employed in the button industry.

The process started with clammers, who harvested huge numbers of mussels from the river, usually between April and November. Captured mussels were put in a trough, covered with water and heated up with a large fire underneath; the heat coaxed the shells to open up, so the flesh (and maybe a pearl) could be scooped out. The flesh was sometimes saved and used to supplement livestock feed. If you fed it to pigs, though, you had to switch them to a regular diet a few months before slaughter or your pork tasted fishy.

Hundreds of clammers and their families lived in a camp on the Muscatine riverfront, apart from the people who lived in town. The clammers kept to themselves and were generally looked down upon by most people in town.

Cleaned shells were transported to the factories, where machines stamped out holes in each shell. The stamping process produced a lot of waste, perhaps 40% or more of the shell; the remnants accumulated in big piles around town, and were sometimes disposed of in the river. George Gebhardt found one way to use the waste: he crushed them and sold the powder for use as feed, filler, and fertilizer.

Factory workers endured difficult conditions for low wages. Many were injured (severed fingers were common) and most were paid just enough to survive but not enough to get ahead; many workers didn’t make enough to cover both rent and food. Some factories paid workers using a piece work system in which their pay was based on how many finished items they made; abuses in that system were common, cheating workers out of a lot of cash. Workers began organizing as early as 1899 but didn’t get very far until they affiliated with the American Federation of Labor in 1910.

Conflict erupted the following year. Union organizers, meeting in secret—they would be fired if owners knew about their organizing activities—began to spread rumors that they were going to strike. It was meant as a ploy to get the owners to negotiate, but the owners responded with a lockout, then slowly reopened with replacement workers. Sporadic violence broke out, much of it aimed at the replacement workers.

City government sided openly with owners. At one point, the owners hired an outside security firm to protect their property and harass the strikers. Owners frequently hired outside security companies to beef up protection. The Pinkerton’s were a favorite firm that owners brought in to bust unions, often through kidnappings and beatings. In the 1911 conflict, the enforcers were nicknamed “The Sluggers”, a brutal group of hired guns—many of them hired from the stockyards of Chicago and St. Louis—who used violence as their first and only means of putting down opposition. When The Sluggers beat an 8-year old child, the tide turned and a large crowd swarmed into the city center, surrounding the Commercial Hotel where the Sluggers were staying and threatening to burn them alive in the hotel.

The sheriff intervened and promised to kick out the enforcers, which he did. He then called in the state militia, who stayed for four days to keep things quiet. The governor convened a meeting of representatives from owners and workers to meet, which resulted in a few small steps forward, including the owners essentially agreeing to recognize the union and a few measures to improve safety. The plants reopened, but the calm didn’t last long. When conditions in the plants didn’t improve much, the union called a general strike in the fall of 1911 that lasted for several months.

At the center of many of the battles was a woman named Pearl McGill. Yes, Pearl was her real name. McGill began her career at age 16 as an industrial spy, hired to let company owners know what was really happening inside their factories and to turn in any union organizers. As she witnessed the difficult working conditions and low pay, she became more and more sympathetic to the plight of the workers, eventually becoming a full-fledged union activist with the Button Workers Protective Union. During her years in the union, she climbed the ranks of the male-dominated leadership, becoming a well-respected organizer for the International Workers of the World.

For the next 20 years, there would be on and off conflict between labor and management before major agreements were finally reached, just as the industry was in decline. Many plants had already closed and the ones that stayed open were switching to plastic, which required far fewer workers. Other factories that survived eventually closed as cheap imports flooded the US markets. In 2013, three companies still made buttons in Muscatine: J & K Buttons, McKee Button Company, and Weber & Sons. All made buttons from plastic; the last pearl button manufacturer, the Ronda Button Factory, closed in 1967.

The process of producing those billions of buttons devastated native populations of fresh-water mussels. Some efforts are being made to bring them back, which isn’t just for grins. Mussels filter water, thus making the river cleaner.

Those early leaders in the button business didn’t fare much better than the mussels. After he was forced out of the factory he founded, John Frederick Boepple worked with the Fairport Biological Station to research ways to replenish the mussel population. In 1911, he walked into a river in Indiana to check out a bed and cut his right foot on a sharp shell, which led to blood poisoning. He was very ill for months before finally dying January 30, 1912 in Muscatine.

Pearl McGill moved to Chicago and became a prominent organizer, involved in the textile strikes of 1912. In spite of her labor activism, her goal had long been to become a teacher. That finally happened thanks to a gift from Helen Keller that paid for her education. She got a job in Buffalo, Iowa but her career was cut short when she was murdered on April 30, 1924, just a couple months shy of her 30th birthday. Her ex-husband was blamed, but some have wondered if she was knocked off by industry bosses, motivated by rumors that she was considering restarting her activist career.

Life After Button Manufacturing

Muscatine labor battles weren’t restricted to the button industry. In 2009, Grain Processing Corporation (GPC) locked out 300 employees who belonged to the United Food and Commercial Workers union. The plant makes corn syrup, corn oil, corn-based alcohol products, and other corn-based goodies. The union was locked out after the company owners insisted on new contract language that would have given them the right to replace union workers with non-union workers. The union pretty much lost the fight, as the company brought in replacement workers; it is a non-union shop today.

On a more positive note, two bored friends, Joe Crookham and Myron Gordin, got the idea to build lighting structures for sporting events and venues. Their plan led to Musco Lighting, which has built giant light panels for several Olympic Games, NCAA sporting events, and several Super Bowls.

Exploring the Area

The National Pearl Button Museum (117 W. 2nd St.; 563.263.1052) chronicles the city’s pearl button industry in fascinating detail, while also showcasing other major industries in the city.

The current St. Mathias Catholic Church (215 West 8th St.; 563.263.1416) is an ornate and architecturally eclectic building that is the heir to the much simpler original church designed by legendary frontier priest Father Samuel Mazzuchelli. For a fun study in contrasts, visit the old church first—it’s on the front side of the complex—then tour the new building.

Parks Along the Mississippi River

Weed Park (Park Dr.), named for James Weed (he donated the land) and not the type of vegetation that might or might not grow there, is a popular spot for summer fun, with a nice overlook of the river, rose gardens, and Indian mounds, plus the usual park amenities; it’s on the northeast part of the city.

For a nice view of the river and Muscatine, drive up to the Mark Twain Overlook (2nd St. at Highway 92).

Riverside Park (Mississippi Dr.) runs along the Mississippi River near downtown; aside from a few nice places to watch the river, you’ll also find Erik Blome’s monumental work Mississippi Harvest, a 28-foot tall bronze sculpture of a clammer.

Musser Park (Oregon St.) covers 11 acres on the southeast part of town, with a skate park and some good views of the Mississippi.

Sports & Recreation

The Running River Trail System currently has 10 miles of paved, multi-use paths that aren’t all connected but someday will be. You can find one trailhead at Musser Park; other sections run along the river.

Culture & Arts

The Muscatine Art Center (1314 Mulberry Ave.; 563.263.8282), housed in the former Laura Musser Mansion, hosts interesting rotating exhibits, as well as period furnishings; free admission.

Entertainment and Events

Farmers Market

Looking for fresh produce? Muscatine hosts a farmers market on Saturday mornings (7:30-11:30) at the corner of 3rd and Cedar Streets and on Tuesday afternoons in the parking lot of the Muscatine Mall (Park Ave.). The markets generally operate from May through October.

Festivals

Shake off the winter cobwebs at the Melon City Criterium, one part of a weekend of bike races in Burlington, Muscatine, and the Quad Cities. The Muscatine race takes place in Weed Park on the Sunday of Memorial Day weekend.

Muscatine is covered in Road Tripping Along the Great River Road, Vol. 1. Click the link above for more. Disclosure: This website may be compensated for linking to other sites or for sales of products we link to.

Where to Eat and Drink

Big Cat’s Café (101 W. Mississippi Dr.; 563.261.7458), located in a historic building along the riverfront, serves coffee and tea, plus a few options for breakfast and lunch.

The Coffee Belt (210 E. 2nd St.; 563.264.6963) can also supply your caffeinated beverage of choice, which you can enjoy in the inviting space or take with you.

Grab some local flavor at Contrary Brewing Company (411 W. Mississippi Dr.; 563.261.7446), a craft brewery with good views of the river. You can sample their beers with a snack or pizza.

Miss’ipi Brewing Company (107 Iowa Ave.; 563.262.5004) is a large and sometimes boisterous place that buzzes on weekends, and rightly so. The food is good, and there’s a nice selection of beers that actually taste like beer.

The Riverside Restaurant (303 E. 2nd St.; 563.263.3616) is the place for a traditional diner-style, hearty breakfast or lunch.

I could call the Yacky Shack (163 Colorado St.; 563.264.8007) Korean-Chinese fusion, but it wouldn’t explain the tacos or General Tso’s chicken sandwich. The place serves an unusual mix of menu items, including the namesake Yacky, which is a delicious fried dumpling stuffed with an ingredient of your choice.

Salvatore’s (313 E. 2nd St.; 563.263.9396) is run by sweet people who know how to make good pizza, salads, and sandwiches.

If you’re looking for a splurge with a view, Maxwell’s at the Merrill Hotel and Conference Center (119 W. Mississippi Dr.; 563.263.2600) can satisfy both. The menu consists mostly of steaks and fish, with solid choices for sides and salads, all of which you can enjoy with those scenic river views.

Where to Sleep

Budget

The Muskie Motel (1620 Park Ave.; 563.263.2601) offers no-frills budget rooms that are clean and in good shape.

If you prefer the predictable banality of a chain motel, most of them are clustered along Highway 61.

Bed-and-Breakfast Inns

Strawberry Farm Bed & Breakfast (3402 Tipton Rd.; 563.262.8688) offers five guest rooms in a country retreat a few miles outside of Muscatine.

Moderate and up

If you’re looking for a night (or more) of pampering, check into the Merrill Hotel & Conference Center (119 W. Mississippi Dr.; 563.263.2600). Rooms are modern and elegant, and many have views of the Mississippi River. Relax in the saltwater pool or sip a cocktail in the lounge while watching the river flow by.

Resources

- Musser Public Library: 408 E. 2nd St.; 563.263.3065

- Post Office: 3100 Cedar St.

- Newspaper: Muscatine Journal

Where to Go Next

Next town upriver: Fairport

Next town downriver: Muscatine Island

Community-supported writing

If you like the content at the Mississippi Valley Traveler, please consider showing your support by making a one-time contribution or by subscribing through Patreon. Book sales don’t fully cover my costs, and I don’t have deep corporate pockets bankrolling my work. I’m a freelance writer bringing you stories about life along the Mississippi River. I need your help to keep this going. Every dollar you contribute makes it possible for me to continue sharing stories about America’s Greatest River!

Muscatine Photographs

A Song for Muscatine

Muscatine by the Mike and Amy Flanders Band; from Where You Are (2014)

©Dean Klinkenberg, 2024, 2021, 2018,2013,2011

En el 2015 estuve ahí es un lugar increíble lleno de historia por cierto me asustaron en la fábrica de botones que ahora está abandonada pero en pie

Buena chocoaventura

I don’t remember coming across a name for the camp. Anyone else know?

Did the clammers’ camp in Muscatine have a name?