Introduction

Nauvoo is a town with an outsized history, where big dreamers and idealists came to make their plans a reality and where some of those dreams sparked epic conflicts, especially during the town’s Mormon era. While much of the town’s Mormon history has been preserved (and nicely buffed and polished for public consumption), it takes some digging to explore the rest of Nauvoo’s fascinating history.

Visitor Information

Visitors can get their questions answered from the Nauvoo Tourism Office (1295 Mulholland St.; 217.453.6648).

History

Early History

The area around the Des Moines Rapids has a long history of human activity, from Paleo-Indians some 12,000 years ago to the Sauk (Sac) and Meskwaki (Fox) nations who moved into the region in the 18th century after the Ho Chunk (Winnebago), Mamaceqtaw (Menominie), and Bodéwadmi (Pottawattamie) nations had called the area home. At the turn of the 19th century, Meskwaki Chief Quashquema led a large village at the future site of Nauvoo of perhaps 500 lodges and several thousand people.

In 1804, a contingent of Sauk and Meskwaki representatives, including Chief Quashquema, went to St. Louis to secure the release of one of their own who had been imprisoned. They also hoped to negotiate a trade deal with terms as favorable as the one given to their rivals, the Wah-Zha-Zhi (Osage). While in St. Louis, the new Governor of Louisiana Territory (and future President) William Henry Harrison took advantage of the situation to induce the group to cede a portion of their ancestral lands, the territory east of the Mississippi River and between the Illinois and Wisconsin Rivers. The US government paid $2,234.50 in goods and cash for the land, plus an annual payment of $1,000 in goods (that the Sauk and Meskwaki had to pick up at St. Louis). The Sauk and Meskwaki retained hunting rights in the area, though.

In 1805, Jean Pierre Chouteau, the newly appointed Indian agent, established a trading post that was supposed to supply the Sauk and Meskwaki with goods at reasonable prices. He and his agent, William Ewing, built a two-story log cabin, but it didn’t work out, apparently because Ewing wasn’t very good at the job. Lieutenant Zebulon Pike met Ewing during his 1805-1806 expedition and called him “utterly unfit” for the work. A few more agents came and went until the cabin was essentially abandoned around 1810.

In 1824, Captain James White bought the land claim and the cabin and set up his own trading post. He didn’t do much better. He couldn’t compete with the American Fur Company, so he closed the post and turned to helping boats transport their goods across and around the Des Moines Rapids, a process called lightering. White also purchased the hunting rights from the Sauk and Meskwaki who then moved across the river to Iowa.

When the post office was established in 1830 (George Cutler was the first postmaster), the settlement was named Venus. By 1832, Venus counted 62 residents. Cutler died in 1834 and one month later the village’s hundred or so residents decided they needed a better name, so they chose Commerce, perhaps hoping the name would be prophetic. It wasn’t. Around the same time folks laid out an official plat for Commerce, the financial panic of 1837 devastated the little town and most of its residents moved away.

Commerce Becomes Nauvoo

As the little town of Commerce was growing and shrinking, Joseph Smith was shepherding followers of a new religion that he founded in 1830 that he first called the Church of Christ but that we know today as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church). He would eventually leave New York and establish communities of believers, Mormons, in Ohio and Missouri, where they faced considerable hostility from their neighbors and were forced to move on.

When Smith and his followers were forced out of Missouri in late 1838, some 5,000 refugees crossed the Mississippi into Illinois where they found temporary refuge in Quincy and Adams County. Most were in rough shape after the journey—physically exhausted, hungry, and desperately poor. Illinois residents offered them safety, food, and supplies, which gave the Mormons the space to regroup, even as their leader, Smith, was stuck in jail in Missouri. Nevertheless, the other church leaders didn’t waste much time looking for a new home.

Within a short time, the village of Commerce caught their attention. As a result of the economic crash, there was a lot of cheap property in the village and reaching it was pretty easy, thanks to its location on the Mississippi River. The first Mormon to buy property in Commerce was Sidney Rigdon who moved to town on April 1, 1839. Joseph Smith bought land in Commerce after escaping from jail and relocated his family to Commerce on May 10, observing that the entirety of the village was “…one stone house, three frame houses, and two block houses.”i They bought much of the land from Dr. Isaac Galland, an intriguing character who had a complicated relationship with Smith and the Mormon community.

Smith and the other leaders executed a new village plat that laid out a street grid over one square mile of land: four-acre lots were platted, each of which was then subdivided into four one-acre lots. Each lot was intended to provide enough space for a home, a garden, and room for domesticated animals to roam. At the end of 1839, Smith renamed the village of Commerce. The new name, Nauvoo, was derived from Hebrew; Smith said it meant “a beautiful location, a place of rest.”ii The change became official the following year, on April 21, 1840, when the US Post Office in Washington DC recorded the new name. It wasn’t just a simple rebranding, either. Smith had a vision for the new city that was, in many ways, a Utopian community, just one that would be built on the doctrine of the new church. Smith wanted to build a Mormon holy city.

At the end of 1840, the Illinois legislature approved incorporation papers for the City of Nauvoo. Based largely on the charter written for the City of Springfield, Illinois, the document granted charters for three entities: one for the city government, one to incorporate a university—the University of the City of Nauvoo—and a third to incorporate a militia, the Nauvoo Legion. The city charter, while not unusual for Illinois at the time, gave Smith the tools to fulfill his vision of establishing an independent government for his community of Mormons that would operate mostly independently of the State of Illinois. Given the hostility Mormons had faced in other places, you could hardly blame Smith for wanting greater control of the institutions that had often been used against Mormon communities.

One of the powerful tools granted to Smith and Nauvoo in the charter was a provision which empowered the city council to determine if Nauvoo residents could be detained on any criminal charge (habeas corpus). This provision, in practice, made it nearly impossible to arrest anyone within the city limits without the approval of the city council, which almost never happened, especially if a non-Mormon was trying to arrest a Mormon.

While the original intent of the habeas corpus provision may have been to prevent the indiscriminate and unjustified detention of Mormons (in other places, Mormons had often been arrested for frivolous or false charges), in practice the city used it to free any Mormons arrested anywhere for any cause, including Smith. This led to the perception at the time—justified or not—that Nauvoo had become a haven for criminals and that Mormons could commit crimes with impunity, an issue that grew increasingly contentious with Nauvoo’s neighbors.

While the provisions in the Nauvoo charter weren’t especially unusual for the time, under Smith’s leadership Nauvoo’s leaders built a government that eliminated any pretense of separation of powers. Under the charter, the mayor was also the chief justice of the local court, and the board of aldermen served as associate justices. In addition, the mayor was the leader of the local militia, the Nauvoo Legion. The mayor therefore had control of civil government, the court, and a militia. While John C. Bennett served as Nauvoo’s first mayor, Smith was the power behind the scenes. In 1842, after Bennett fell out of favor and was excommunicated, Smith was chosen mayor and wielded power openly.

Smith was intent on consolidating the Mormon faithful into a single location. This helped fuel very rapid growth at Nauvoo—the city counted 12,000 residents by 1844, plus several thousand more Mormons lived outside the city in places like LaHarpe, Lima, Ramus, and a few communities in Iowa. In contrast, most of the non-Mormon communities nearby, places like Pontoosuc and Warsaw, had no more than 300 residents. Among those who moved to Nauvoo were nearly 5,000 English Mormons who emigrated to the US. Most of the English immigrants were former factory workers who were poor and not well adapted to the rural life of Nauvoo.

Smith’s initial plan was that residents would have a home in the city and land to farm outside of it. Smith hoped that wealthy Mormons would purchase the needed land on behalf of the community, then the church would divide up the land according to need, but there were far more needy Mormons than there were wealthy ones. George Miller in 1841 wrote:

Besides these, [others] were crowding in from the States, all poor, as the rich did not generally respond to the proclamation of the prophet to come with their effects…iii

As Mormons arrived in their new city, tents gave way to temporary log huts, until proper houses could be built. In order to expedite construction, the church acquired its own logging camp in Wisconsin along the Black River. It was originally meant to provide building materials for a hotel (Nauvoo House) and for a new temple but much of the lumber was diverted for home construction. In 1843, the Mormon-run logging camp floated 600,000 board feet of lumber downriver to Nauvoo.

The growing community drained swamps to make the village more habitable, but many people still died from “swamp fever” (probably malaria). The early economy relied heavily on cottage industries and bartering was extensive because there just wasn’t a lot of cash. Residents quarried rock from the bluffs and built brick factories to manufacture basic construction materials. Soon they had a fully developed small city with foundries, saw mills, leather shops, wagon makers, lawyers, clothiers, a photographer (using Daguerreotypes), and much more.

Community life developed quickly, too. Nearly two dozen common schools were established, like the Nauvoo Select School where students studied the classics. Concerts were held regularly, with music from bands such as the Nauvoo Military Band (drums), the Nauvoo Brass Band, and the Nauvoo Quadrille Band (string and reed instruments).

Nauvoo was something of a tourist hot spot during the years the Mormons lived there. Charlotte Haven arrived in Nauvoo in January of 1843–not the most hospitable time of year–for a lengthy visit. Her initial impressions were fantastic and contradictory:

At eleven o’clock we came in full sight of the City of the Saints, and were charmed with the view. We were five miles from it, and from our point of vision it seemed to be situated on a high hill, and to have a dense population; but on our approach and while passing slowly through the principal streets, we thought that our vision had been magnified, or distance lent enchantment, for such a collection of miserable houses and hovels I could not have believed existed in one place.iv

Josiah Quincy, who reached Nauvoo in May 1844, had a different impression. He observed:

The curve in the river enclosed a position lovely enough to furnish a site for the Utopian communities of Plato or Sir Thomas More; and here was an orderly city, magnificently laid out, and teeming with activity and enterprise.v

Smith often met visitors personally, especially if they were of some importance. Some of those visitors, like renowned priest Samuel Mazzuchelli, came to discuss theology with Smith.

At one time, Smith floated a plan to dig a canal that would have run two miles down the middle of town, along what is roughly Main Street today. When a major deposit of limestone was discovered at the north end of the route, the plan was abandoned, although some of that limestone ended up being quarried for a grand temple.

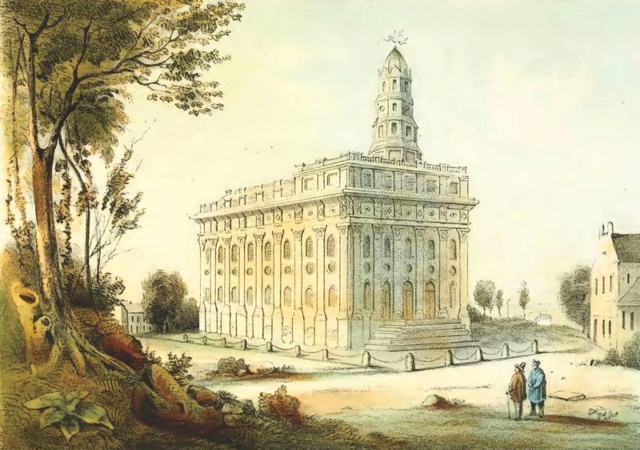

Construction of the new temple began in 1841, using a design that Smith came up with. When completed (after Smith’s death), the temple would rise 165 feet from the ground to the top of the tower. It was built of white limestone and of wood harvested from the northern forests. The basement housed a large, oval baptismal font (16 feet by 12 feet and 4 feet deep) that sat elevated on the backs of a dozen life-sized oxen carved from wood (probably later replaced by stone statues). The font was encircled by a seven-foot wall of carved stone. Worshipers climbed steps at either end of the font to enter the basin to conduct baptisms of the dead, the first of which were held in the temple on November 21, 1841.

The temple sat atop the hill at a sharp turn on the river, creating a dramatic scene that dominated the sight lines and gave boatmen a new landmark. Henry Lewis, who painted one of the popular Mississippi River panoramas in the mid-19th century, included a detailed portrait of the temple in his book Das Illustrirte Mississippithal. By the time Lewis exhibited his rendering of the temple, it had been severely damaged by a fire, arson, in all likelihood.

The other major building project that Smith envisioned was Nauvoo House, a space that he wanted to be part boarding house and part retreat center. Although construction began in 1841, Smith gave up on it in the summer 1843, instead building a new wing on his house that served as a hotel. L.C. Bidamon, who later married Smith’s widow, Emma, purchased the half-built remains of Nauvoo House. He stripped the building to the basement and built a more modest structure, a house, on part of the foundation. In the 20th century it was used as a youth hostel for a while; it is available today for overnight rental for large groups.

Smith pushed for a commercial district on Main Street but a competing one developed up the hill, on Mulholland Street (where it is today), developed by individuals who would later became rivals of Smith. Some of them would be involved in the publication of the Nauvoo Expositor that triggered the conflict that led to Smith’s death.

Nauvoo became increasingly insular the larger it got. The city was run by a small group of church leaders who didn’t share the details of their decision-making with the citizenry, which contrasted markedly with the more or less transparent governments of the places around Nauvoo. Differences between Mormons and their neighbors grew over time and conflicts escalated. Particularly contentious were issues related to punishing lawbreakers, which led to a system where county residents were essentially served by separate justice systems. Mormons accused of crimes got Mormon juries that usually acquitted them, while non-Mormons got sympathetic juries of their peers who were reluctant to convict.

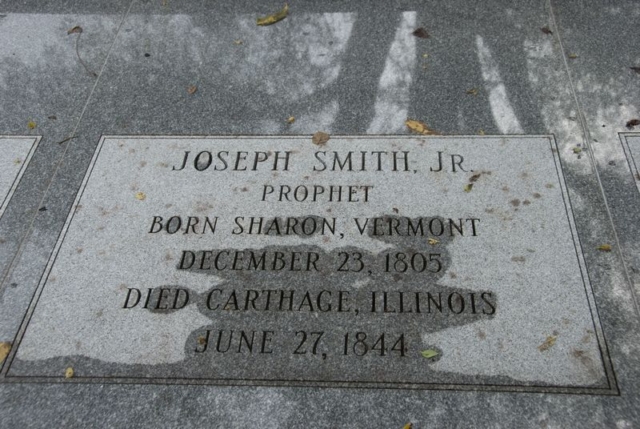

The incident that ultimately sparked the end for Nauvoo’s Mormon community was the murder of Joseph Smith on June 27, 1844. The events that led up to his murder say much about the state of affairs around Nauvoo at the time.

A schism had developed in the church between Smith and a few other prominent members over plural marriages, the treatment of women in Nauvoo, and Smith’s leadership. This group was eager to start a reform movement, but Smith—the Prophet who was the sole voice through which God communicated to the community— wouldn’t allow other sects of Mormons to establish themselves, so he waged a campaign to discredit the dissenters.

The rebel sect published their grievances on June 7, 1844 in a paper called the Nauvoo Expositor. Three days later, the city council, at Smith’s urging, declared the paper a public nuisance and Smith ordered the destruction of the paper and its printing equipment. The publishers fled to Carthage out of fear for their safety, then filed a warrant for Smith’s arrest for inciting to riot. On June 11th, a Hancock County court issued a warrant for Smith’s arrest. Smith turned to Nauvoo’s municipal court, which dismissed the charges.

This excited Smith’s detractors in Warsaw and Carthage, who railed against his actions and the unwillingness of the Nauvoo court to arrest Smith. Smith initially had planned on fleeing to the Rocky Mountains, but after crossing the Mississippi River into Iowa, he changed his mind. On June 25, he and his brother, Hyrum, met with Governor Thomas Ford in Carthage and agreed to turn themselves in to face the charges. At their preliminary hearing, they were granted bail of $500, but they were then quickly charged with a new crime: treason. The treason charge grew out of accusations that Smith used the Nauvoo Legion to resist arrest from state law enforcement. Bail wasn’t an option for someone charged with treason, so the Smith brothers were housed in the Carthage jail. Governor Ford authorized an independent militia to protect the Smiths after personally pledging to vouch for their safety.

On June 27, Governor Ford went to Nauvoo in an attempt to calm tensions but while he was there, a group of men with their faces painted black, probably from the Warsaw posse, stormed the Carthage jail around 6pm, probably with the pre-arranged help of guards who offered no resistance. Hyrum was shot and killed almost right away. Smith, probably wounded by a hail of gunshots after firing a few shots in defense, managed to jump out of a window. Most eyewitnesses testified that Smith did not survive the fall.

Nine men were charged with murdering Smith, including Thomas Sharp, the editor of the Warsaw Signal, who had written that Smith’s murder was regrettable but justified. Five men, including Sharp, went to trial in May 1845, but all were acquitted after a sensational trial. The defense benefited tremendously when it managed to get the first jury dismissed and replaced with a new panel that didn’t have a single Mormon on it. Besides that, the prosecution’s cause got more difficult when all the Mormon witnesses refused to testify; they were apparently afraid that they would be the next victims if they did so.

Joseph and Hyrum Smith laid in state at the Smith mansion in Nauvoo; ten thousand people viewed their bodies. Joseph Smith was just 38. His death left a leadership vacuum that was eventually filled by Brigham Young. Some Mormons thought the rightful heir was Smith’s oldest son, Joseph III, but he was only 12 at the time.

Smith’s widow, Emma, was worried about the graves being disturbed, so the Smiths were buried in secret, first under the Nauvoo House, then at another location where they stayed until 1928 when they were reburied in their current graves.

Young got busy reassuring the faithful that of his leadership skills. He pushed ahead with temple construction; the exterior was completed in October 1845. The final cost of construction, while hard to know, probably approached a million dollars. Mormons wouldn’t use the temple for long, though.

Conflict erupted again between Mormons and non-Mormons in the fall of 1844. A group of Warsaw citizens prodded Governor Ford to expel the Mormons but Ford said he lacked the authority to do so. After the fall harvest, a few groups advertised a “wolf hunt” in local newspapers, which was a code for a raid on Mormon settlements. After mobs ransacked Mormon-owned farms, Ford brought a militia back to Carthage in late October to keep the peace.

The quiet held through the winter, but the growing hostility toward the Mormon community at Nauvoo spread to the state capital. On January 29, 1845, the Illinois legislature revoked the Nauvoo charter, even though Governor Ford had only supported amending it. Nauvoo hunkered down in the face of the hostility. The Legion was deployed around city blocks to control entrance to and exit from the city.

When mob violence against Mormons began again in the summer of 1845, Mormons organized their own militia—with the help of a friendly county sheriff—and pushed back enough to occupy Carthage. Governor Ford organized a militia to replace the Mormons at Carthage but by that time he and other state leaders had apparently decided it was time for Mormons to leave the state anyway.

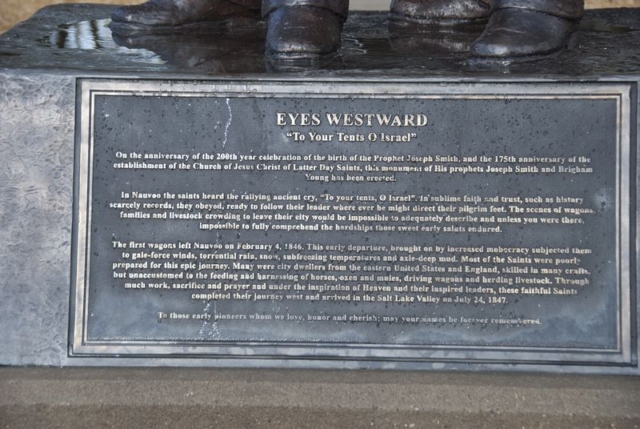

Facing increasingly intense public pressure, the Mormon leadership announced in September 1845 that they would abandon Nauvoo by the following spring. Unknown to most people, the Mormon leadership had quietly been exploring and preparing for a move west for some time. In February, 1846 the first thousand residents moved out, including most of the leadership; Brigham Young left on February 15. Getting everyone out was no small task.

The first group walked across the frozen Mississippi River. In spring, ferries transported thousands of residents across the river to Iowa where many lived in temporary camps. Most had to sell their land and property at deeply discounted prices. Hundreds of Mormons were still in Nauvoo in the summer when violence broke out again but the Mormons fought back the most serious threats. The so-called “Battle of Nauvoo” was fought on September 12, 1846, which was about an hour of gunfire between 700 anti-Mormon agitators and 300 residents of Nauvoo, most of them Mormons.

That incident motivated most of the remaining Mormons to leave. The small number who remained in Nauvoo was no longer perceived as a threat. Among those who stayed behind was most of Joseph Smith’s family: his mother, Lucy; his sisters and their families; his widow, Emma, and their four sons and adopted daughter. Joseph Smith III would later become the leader of a break off branch of Mormons called the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, today known as the Community of Christ. He assumed the leadership in 1860 but later moved to Independence, Missouri where he established the new headquarters.

The Mormons left behind a lot of infrastructure: about a thousand log houses, nearly 300 brick homes, and another 300 frame houses. In 1845, Hancock County was the most populous county in Illinois with 22,559 residents, and Nauvoo was the largest city with just over 11,000 residents. Just five years later, the entire county had 14,652 residents and Nauvoo about 1,200.

Charles Lanman, who passed through Nauvoo after the exodus wrote of the abandoned city:

The Mormon City occupies an elevated position, and, as approached from the south, appears capable of containing a hundred thousand souls. But its gloomy streets bring a most melancholy disappointment. Where lately resided no less than twenty-five thousand people, there are not to be seen more than about five hundred; and these, in mind, body and purse, seem to be perfectly wretched…When this city was in its glory, every dwelling was surrounded with a garden, so that the corporation limits were uncommonly extensive; but now all the fences are in ruin, and the lately crowded streets actually rand with vegetation. Of the houses left standing, not more than one out of every ten is occupied, excepting by the spider and toad. Hardly a window retained a whole pane of glass, and the doors were broken, and open, and hingeless.vi

Some of the infrastructure fared better than others. In 1848, the Mormon temple was partially destroyed by a fire that was later determined to be arson; the remaining bits were destroyed by a tornado in 1850.

Sorting through the events at Nauvoo is a difficult task. Nauvoo remains a revered place for Mormons. The story of Mormon Nauvoo is both inspiring and tragic, a place where the community came together in the face of violent opposition, but also the place where its founder was murdered. Besides that, many key theological concepts of the church were developed here, like baptism of the dead. For this reason, some historical pieces written by Mormons are focused more on myth-making than a fair accounting of events. On the other hand, many of those involved in expelling the Mormons from the area downplayed the hypocrisy and cruelty of their own actions.

Ultimately, it seems that much of the opposition to the Mormons arose primarily from civil and not religious concerns, even though some Mormon practices (like polygamy) undoubtedly aroused strong opposition. Accusations of crimes committed by Mormons that went unpunished fueled some of the opposition, even if it’s hard to figure out today how widespread those criminal acts actually were.

But accusations of lawlessness were only part of the dynamic. People who settled on the frontier strongly valued the democratic process; they were egalitarian in orientation and tended to value the rights of the individual over communal rights. Joseph Smith’s Nauvoo represented very nearly the polar opposite of these frontier values. He had established a community ruled by a small group of religious elites who demanded that community members conform to the dictates of the leaders. Smith’s opponents decried the concentration of power into the hands of just a few people.

In 1844, the Quincy Whig printed an anonymous letter that summed up these feelings:

The spectacle presented in Smith’s case—of a civil, ecclesiastical, and military leader, united in one and the same person, with power over life and liberty, can never find favor in the minds of sound and thinking Republicans.vii

The whole setup was perhaps far too similar to the old world governments that many on the frontier thought they had left behind, and the size of the Mormon population created fear that Mormons would impose a similar style of government on everyone, regardless of their religion.

John Hallwas, who has researched extensively the events at Nauvoo asserted that the whole affair was an ideological conflict in which both sides ditched their commitment to pluralism in favor of self-interest. Mormons suppressed internal opposition even as they trumpeted their commitment to liberty, while their non-Mormon antagonists trumpeted their commitment to democracy even as they resorted to mob violence to drive out the Mormons. He makes a compelling case.

Whatever the causes, they were complex and marked by attempts from all around to push a narrative that favored one side over the other, when, in fact, there was plenty of blame to go around. Regardless, it all makes for one heck of a story.

More Utopians Move to Nauvoo

After the Mormons were forced to leave Nauvoo, Etienne Cabet, another idealist with big plans, founded a new Utopian community in the same place, leading his followers across an ocean and up a river to establish the community of his dreams, even if he was slow to embrace the work required to make it happen.

The French-born Cabet was a visionary and anti-monarchy activist prone to getting in trouble with the powers-that-were. In 1834 he was convicted of printing accusations that were “an affront to the king.” For his punishment, he was allowed to choose between five years in exile or two years in prison; he chose exile, in England. He put his time to good use. In 1839, he published a novel called Voyage en Icarie (Voyage to Icaria), a romance influenced by Thomas More’s Utopia.

In the novel, William Carisdall, an English man of noble birth, sails to an island nation off the coast of east Africa. After kicking out the last of their dictators, the residents of the island had built a new society under the leadership of a benevolent dictator named Icar, who led the transition until his death, at which time the country became a democracy. In the book, the residents of this fictional island lived in a community without money and where the community owned everything; Cabet’s central premise was that the major cause of misery and conflict in the world was private property.

The book inspired quite a following. Shortly after its publication, Cabet’s exile ended and he went back to France where he advocated non-violent reform and organized Icarian chapters around the country, about three dozen of them. It wasn’t long, though, before Cabet’s efforts were derailed. France sank into economic depression, and the political turmoil it spawned led to a repression that did not spare the Icarian movement.

Cabet wasn’t about to let go of his dreams, though, so he decided to start an Icarian community in the US, announcing it with great fanfare on the front page of his newspaper, Le Populaire, on May 9, 1847: Allons en Icarie! (Let’s go to Icaria!). In spite of Cabet’s enthusiasm for the idea, most French Icarians weren’t crazy about starting a new community on the other side of the Atlantic. They preferred to stay in France and fight.

Cabet really didn’t have the foggiest idea about how to get the new community going. He agreed to a land deal where the Icarians had a shot at getting 3,000 acres along the Trinity River in Texas for nothing. All they had to do was build 3,000 homesteads by July 1, 1848. The parcels, however, weren’t contiguous, which wasn’t going to make a nearly impossible task any easier.

Nevertheless, he organized a group to leave France (69 people), which left for Texas on February 3, 1848 after paying Cabet 600 francs each to join the group. Cabet was not among that initial group. He remained in France where he tried to aid the revolution, but when public opinion turned on everyone who had once supported any form of communist ideology, Cabet was finally forced to flee France for his own safety.

Those first Icarians reached New Orleans about seven weeks after leaving France, in late March 1848. An advance guard quickly set out for Texas but the trip from New Orleans was much harder than anyone anticipated and the land itself was barely habitable. A few cabins were built by July 1, but malaria and cholera took a heavy toll; in August, four people died, which was enough hardship to convince the group’s physician to desert.

The whole party soon decided to give up and trudged back to New Orleans to join the larger body of Icarians that had since grown to 480 in number, still without Cabet. When Cabet finally joined his fellow Icarians in New Orleans on January 19, 1849, he found a restless group, many of whom were ready to call it quits. In spite of the hardships, though, a majority voted to continue with the mission; most of the rest (218 people) sailed home with a full refund, then, after reaching France, sued Cabet for fraud.

A couple of weeks after the vote, another advance team returned to New Orleans with news that they found a promising site for the new community, at the (mostly) abandoned city of Nauvoo, where land could be purchased for just the cost of back taxes. Two weeks later the group voted to move there and they were soon on a steamboat, all 280 of them (142 men, 74 women, and 64 children).

They arrived in Nauvoo on March 15, 1849 and bought property around the temple square (that included the ruins of the former Mormon temple), plus some 2,000 acres of nearby farm land. The community came together quickly. In a short time, they had a mill and a distillery running and had opened retail shops in Keokuk and St. Louis for the flour they milled and the whiskey they distilled. (Their whiskey was very popular.)

The Icarians intended to convert the Mormon temple into a meeting house and lecture hall but a tornado in 1850 destroyed what was left of the building. Instead, they used some of the stone to build other structures, including a school where they hung their motto over the door: “From each according to his talent, to each according to his needs.”

Cabet, like the fictional Icar, was the benevolent dictator of the community, acting as the sole, undisputed leader until it was stable enough to select its own government. He handed out work assignments and made all the major decisions. He formed a governing body that gave women a partial voice–they could express their views but they weren’t allowed to vote on many issues.

Life wasn’t too bad. The workday began at 6am. Men began the day with a shot of whiskey and went to work, then took a break at 8am to have breakfast with their families. The work day ended at 6pm. Free education began at age four. The community had a 36-member orchestra that played every Sunday afternoon and a performing arts theater, both of which were popular with non-Icarians, too. In the 1850s, the Icarians claimed the largest library in Illinois, some 4,000 volumes in total.

By 1855, six years after establishing the community in Nauvoo, the Icarian community had grown to 469 people. (They were never more than 25% of the city’s total population, though; most of Nauvoo’s residents were not Icarians). It wasn’t all peaches and cream, however. Some Icarians complained about the food (more peaches and cream!), and several people complained that Cabet was spying on them. (Twenty members left over that charge alone.)

Cabet had to return to France in the summer 1851 to defend himself against the dissidents’ charges of fraud; he was acquitted but he stayed in France another year. In his absence, the Nauvoo Icarians loosened up the strict rules that Cabet had insisted on. When Cabet got back to Nauvoo, he tried to restore his system by pushing through a new set of rules, but his efforts weren’t well received. A majority of Icarians pushed back, charging Cabet with incompetence and challenging his leadership. Cabet wasn’t pleased.

The community muddled through for a couple more years, but Cabet’s decision to push for an amendment to the governing charter in December 1855 was the group’s undoing. Under the existing charter, the president–Cabet–and directors served one-year terms, with half of the directors facing elections every six months. Cabet proposed changing the charter so that the president would serve a four-year term and would be empowered to appoint the directors. When Cabet proposed the change in 1856, some members reminded him that constitutional changes were allowed only in odd-numbered years. When Cabet failed to win re-election as president on August 3rd, open conflict erupted that was bad enough that the non-Icarian neighbors called the sheriff to intervene.

Cabet shouldered much of the blame, so the Nauvoo mayor told him to get out of town. He was formally expelled from the Icarian community in October 1856, but he took 71 men and 44 women with him when he left. Cabet and followers settled near St. Louis where they were ready to build a new Icaria, but Cabet had a stroke on November 7 and died the next day. The group that had followed him from Nauvoo moved to a new location along the River Des Peres on land that was really too expensive for them. They rebuilt their community but after four years of suffering through dysentery and other diseases they were forced into bankruptcy. The St. Louis colony formally disbanded in January 1864.

Meanwhile in Nauvoo, productivity was down and creditors were stalking the community, so in 1860 they decided to sell their holdings and move on, too. They took the $20,000 they got for the property, just one-third of what they hoped to get, and moved to Adams County, Iowa, an area where a few Icarians had moved to in 1852. They struggled for a while, until the Civil War erupted, then, almost overnight, their products (e.g., wool) were in demand from Union soldiers. They made enough money to pay down most of their debts.

Many aspects of life changed for the Icarians as their group shrank. They evolved into a loosely affiliated agricultural commune, with weak leadership and families living in their own houses. Their children even went to public schools. Fresh converts arrived from France in the mid-1870s, committed communists who weren’t too happy with the state of affairs they found in Iowa. The old and new guard eventually sued each other and dissolved into separate communities. Those new bloods didn’t do very well—they lacked leadership, too, and weren’t fond of farming—so a couple dozen relocated to Sonoma County, California as the Icaria-Speranza community before that group fell apart, too.

As for that older group, the last Icarians standing, they built another new community about a mile away from where they first settled in Iowa, but with no new members joining them, they got smaller and smaller throughout the 1880s. The last eight surviving Icarians got together in 1898 and formally dissolved the community.

Remnants of Icarian life lingered into the 20th century. The last of the Icarian home foundations at Nauvoo was removed in 1952; the school was razed in 1972. Some Icarians stayed in the Nauvoo area, and descendants can still be found, like the Baxters, who have been running a winery since 1857.

Cabet’s attempt to translate his Utopian ideals failed for many reasons. For one thing, he had imagined an urban Utopia, which is why the group was composed primarily of middle-class and well-educated people, many of them artists. The community at Nauvoo, however, was primarily agricultural, so the Icarians didn’t really have the experience to succeed under those conditions. Ultimately, though, it seems the community failed simply because of human nature, primarily over struggles for leadership and influence. Even though most members shared Cabet’s vision for the community, they had a hard time agreeing on how to make it work.

Nauvoo after the Mormons and Icarians

Nauvoo had plenty of life after the Mormons and Icarians left. The city had a reasonably busy port in the 19th century. A ferry operated between Nauvoo and Iowa from 1834 to 1946; the last one, called the City of Nauvoo, transported people and their goods across the Mississippi from 1884 to 1946.

After the Icarians left, a number of German and Swiss immigrants moved in. For 50 years, until World War I, Nauvoo had the largest number of German speakers of any place in Illinois. The new residents transplanted much of their culture, including grapevines from home that led to a robust wine-making business in Nauvoo.

Grape-growing and wine-making go back to Nauvoo’s earliest days, however. Frontier priest Father John Alleman may have imported cultivated grapes to Nauvoo as early as the 1840s; he later bought a bell for Saints Peter and Paul Church that included grape vines as a decorative element.

In 1866 Nauvoo had 250 vineyards and dozens of wine cellars, including the Rheinberger vineyards that were planted in 1851 and are still productive today. The wine-making industry did well until Prohibition; only a few vineyards survived that period as much of the land that had been dedicated to grape cultivation was converted to other uses.

After Prohibition, Nauvoo residents who enjoyed sipping wine had the pleasure of pairing it with a well-regarded local cheese, a blue cheese. In the late 1930s, Oscar Rohde opened a factory in town that produced blue cheese from homogenized cow’s milk instead of the sheep’s milk that was typically used. He set up shop in the former Schenk Brewery, taking advantage of the limestone vaults for storing and aging the cheese. His company’s cheese was selected as the best blue cheese in the US in 1983 and won an international competition the year after that.

Rohde died in 1965 but his family continued to run the operation for many years. The plant changed hands a couple of times until it was purchased by Con Agra in 2000, which closed it just three years later and sold the brand names (Treasure Cave and Nauvoo) to Saputo Inc. of Montreal. Con Agra then sold the property to the LDS Church for $100,000—one-tenth of the asking price—who subsequently tore it all down for a parking lot. There have been a couple of attempts to revive production of Nauvoo blue cheese but so far it hasn’t worked out.

A group of five Benedictine sisters arrived in Nauvoo in 1874 and quickly opened a school for girls called St. Scholastica Academy, just two weeks later, on the site where the Mormon temple once stood; the first class had seven students. The sisters renamed the school St. Mary’s Academy in 1879 and went about educating girls for the next 100 years, until boarding schools lost their popularity. The Academy closed in 1997 and the sisters sold their buildings and property to the LDS Church, which razed the complex to clear land around the temple. The sisters used the proceeds from the sale to built a new, eco-friendly home in Rock Island in 2001.

Nauvoo had its ups and down in the 20th century. An explosion in 1909 destroyed some downtown buildings and killed a young child. When the dam was completed at Keokuk, water levels rose some 30 feet, submerging two blocks of the old city. In 1934, the First Trust and Savings Bank went under, taking with it the savings of many locals.

After a couple of generations of distance, a few Mormons came back to Nauvoo to visit or preach. In 1903, the LDS Church bought the Carthage Jail where Joseph and Hyrum Smith were killed. In 1909, the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (now called the Community of Christ) started buying up the property that had once belonged to Joseph and Emma Smith. In the 1930s, the LDS Church bought a small lot near the site of the Temple, and over the years bought additional parcels as they became available.

Soon after that, restoration of the surviving buildings began, starting with the home of Heber Kimball, one of the Twelve Apostles in the early church, by his Utah-based great grandson, Dr. J. LeRoy Kimball. Interest in wholesale preservation soon took off after that. Kimball and the LDS Church started buying up land and transferring it to Nauvoo Restoration, Inc. after its creation in 1962. In the course of 25 years, the church has bought 1,000 acres in Nauvoo and has renovated dozens of buildings.

Nauvoo today draws thousands of Mormon visitors who come to explore the city’s past and their connection to it. The steady tourism business has both helped the town financially and irritated some long-time residents who feel that much of Nauvoo’s past has been overwhelmed by the efforts of the LDS church to preserve Mormon history.

I find Nauvoo a fascinating place to visit. In Nauvoo’s history, there are important lessons about the shifting struggle to balance civil government with deeply held religious beliefs, as well as the dangers to civil society when tolerance and respect for others breaks down. As someone who isn’t Mormon, I also find it fascinating to watch how a new religious group actively shapes its mythology, without getting too bogged down in the need to be entirely accurate about the historical details. Nauvoo’s sites may be of greatest interest to Mormons, but even those who are not members of the LDS Church will be fascinated by the Beautiful City.

Exploring the Area

The Weld House Museum (1380 Mulholland St; 217.453.6590; free) explores the breadth of Nauvoo’s history with exhibits on the Mormon era, the Icarian community, the Mississippi River, as well as providing insights into farm life and shopping in a small town general store.

Located in the heart of town, serene Nauvoo State Park (217.453.2512) has a campground, a 1 ½ mile hiking trail, and the Rheinberger House Museum (217.453.6590). The museum presents a wide swath of Nauvoo’s history, from the Native Americans who lived in the area to Nauvoo’s famous blue cheese. The original 4-room house was built during the Mormon era, then in 1850, Liechtenstein natives Alois and Margretha Rheinberger purchased it. The Rheinbergers would eventually add four rooms to accommodate their large family (they had 10 children) and also built a wine cellar, a press room, and a carriage house. Alois’ vineyard, which started with three acres of Concord grape vines planted in 1851, are still producing grapes today.

For a quick overview of the LDS Church and its history in Nauvoo, head to the Historic Nauvoo Visitor Center (350 N. Main St.; 217.577.2603). Don’t be surprised if a young missionary strolls over to say hi and chat for a few minutes. While the LDS Church downplayed evangelizing in the early years of re-establishing a presence in Nauvoo, that’s no longer true today. Communicating the Mormon vision of religion is part of all the historic sites. The visitor center also has a variety of short and feature-length films you can watch.

The Nauvoo Restoration Area comprises some twenty historic properties in the flats near the Mississippi River that have been restored. The area is often brought to life with actors in period dress and craft demonstrations.

While the vast majority of Mormons left Nauvoo in the mid-1840s, the family of the church’s founder, Joseph Smith, stayed put. They went on to found a spin-off sect that was first called the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, but is now known as the Community of Christ. That church owns the former home of Joseph Smith in Nauvoo and leads guided tours of the house and associated sites. Stop in at the visitor center for the Joseph Smith Historic Site (865 Water St.; 217.453.2246) where you can sign up for a short film followed by the guided tour.

The Old Nauvoo Cemetery (East Mulholland St) contains monuments to many early residents of Nauvoo, including Seymour Brunson; it was at Brunson’s funeral that Joseph Smith introduced the concept of baptizing the dead.

In 2002, the LDS church completed construction on a replica of Smith’s Nauvoo temple, a process that took three years and cost about $30 million; a spire rises high above the temple, topped with a golden sculpture of the angel Moroni. The building (50 N. Wells St.) is only open to Mormons in good standing, but everyone else is welcome to walk around the grounds.

At the sound end of town, the Stone Arch Bridge spans a drainage canal dug by the Mormons in the 1840s that was used to drain some of the swamps in the area.

The Carthage Jail (310 Buchanan St.; 217.357.2989), built in 1839, is best known as the spot where LDS founder Joseph Smith and his brother, Hyrum, were murdered on June 27, 1844. The LDS Church has owned and maintained the site since 1903. The site today is devoted to honoring the slain Smiths, who Mormons view as religious martyrs; it is about a half-hour’s drive southeast of Nauvoo.

Entertainment and Events

Festivals

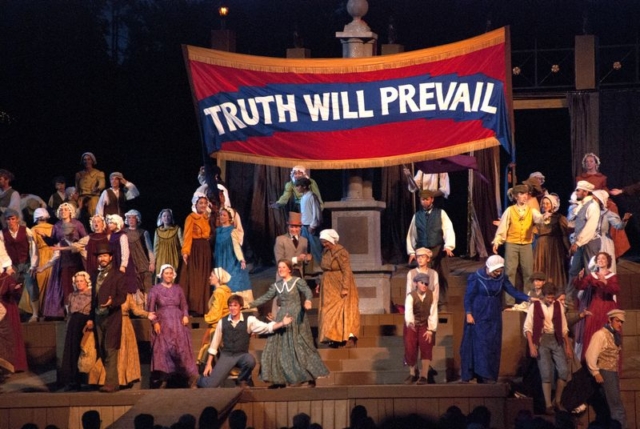

For about four weeks each summer, actors perform an elaborate show called the Nauvoo Pageant (July; free) that tells the origin story of the Mormon religion in a big way, with colorful banners, singing, dancing, and children skipping across stage. The Nauvoo Pageant alternates with the British Pageant, which tells the story of the journey of thousands of British converts to the US and Nauvoo with colorful banners, singing, dancing, and children skipping across stage.

At the end of the summer, Nauvoo hosts its annual Grape Festival (Labor Day weekend), where it celebrates with wine, live music, and arts and crafts.

**Nauvoo is covered in Road Tripping Along the Great River Road, Vol. 1. Click the link above for more. Disclosure: This website may be compensated for linking to other sites or for sales of products we link to.

Where to Eat and Drink

Baxter Vineyards (2010 E. Parley St.; 217.453.2528) traces its origins to 1857 when Emile Baxter and family planted their first grapevines. The family had moved to Nauvoo in 1855 to join the Icarian community and chose to stick around when the rest of the community splintered and moved away. Baxter’s has a tasting room where you can sample their products. The Wine Barrel at Baxter’s has pretty good frozen pizza made by Angelini’s of Keokuk.

Dining choices are pretty limited in Nauvoo, especially in the evening.

The Hotel Nauvoo (1290 Mulholland St.; 217.453.2211) specializes in comfort food that you can order fresh from the menu or enjoy from the very popular buffet. It’s a deceptively large place; the various dining rooms can seat 300 hungry people. The fried chicken and desserts are especially good. The price is reasonable but don’t be surprised when you notice that they automatically add in a 12% tip. People tend to dress a little nicer for dinner here, but it’s not a necessity.

Where to Sleep

Nauvoo has a lot of house and apartment rentals. For a list, check out the Nauvoo tourism website or search in the usual vacation rental sites.

Camping

Nauvoo State Park (217.453.2512) has 150 sites that are rather close together but heavily shaded.

Lodging

Four generations of Krauses have run the Hotel Nauvoo (1290 Mulholland St.) in a building that traces its roots to the 1840s. All rooms are on the second floor and evoke a simple, period feel but are modern and clean. The two suites are large enough for a family.

The same owners offer similar rooms but at ground level at the Motel Nauvoo (1610 Mulholland St.). For both, they take reservations by phone only (217.453.2211).

Sources

i Nauvoo: Kingdom on the Mississippi; Robert Flanders; U of Illinois Press, 1975; P. 39.

ii Glen M. Leonard, “Nauvoo”, in Encyclopedia of Mormonism (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University, 2007), accessed Sept 7, 2015, http://eom.byu.edu/index.php/Nauvoo.

iii Nauvoo: Kingdom on the Mississippi; Robert Flanders; U of Illinois Press, 1975; p. 145.

iv Entry dated Jan 3, 1843; http://www.olivercowdery.com/smithhome/1880s-1890s/havn1890.htm, accessed Sept 6, 2015.

v Figures of the Past; Josiah Quincy; Roberts Brothers, 1883; p. 388.

vi A Summer in the Wilderness: Embracing A Canoe Voyage up the Mississippi and around Lake Superior; Charles Lanman; NY: D. Appleton & Company, 1847; p. 30-31.

vii “The Mormons”, Quincy Whig, May 22, 1844, 1.

Resources

- Nauvoo Public Library: 1270 Mulholland St.; 217.453.2707.

- Post Office: 55 N Barnett St.

- Newspaper: Hancock County Journal-Pilot

Community-supported writing

If you like the content at the Mississippi Valley Traveler, please consider showing your support by making a one-time contribution or by subscribing through Patreon. Book sales don’t fully cover my costs, and I don’t have deep corporate pockets bankrolling my work. I’m a freelance writer bringing you stories about life along the Mississippi River. I need your help to keep this going. Every dollar you contribute makes it possible for me to continue sharing stories about America’s Greatest River!

©Dean Klinkenberg, 2024, 2021, 2018,2013,2011

I read your article and the only critique I would offer is when you were talking of Joseph Smith III and moving the RLDS church headquarters to Independence, MO. This move didn’t occur in 1866. First he moved the headquarters and his family to Plano, Illinois, then he moved on to the community of Lamoni, IA and then finally Independence. This occurred over a 30-40 year period. Other than that detail, I think you did a nice job giving a overall history of Nauvoo.

This was very interesting. I like how you put the people of the Norman religion scrubbed and cleaned their history. They scrubbed and dissolved a good portion of many families history. Nightfall at Nauvoo could be found in a single library in a fifty mile radius of Nauvoo. I don’t know about the rest of the nation. They hit historical societies and were assumed to have been the ones whom took books written of the times that had any negative views. This took place during the beginning of their great geniology endeavors. I happen to have started mine before them, and when I went back publications were gone. Our family belonged and got out over my great grandmother. She was 15 and her parents were not okay with giving her to Smith. She considered them to be theives, they took what they wanted in the name of the Lord.