In 1932, the US Gross National Product dropped a record 13% and nearly one-quarter of the adult population was unemployed; in three years 40% of American banks had failed. In the first few weeks after his inauguration in March 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt launched a series of ambitious public works programs to get people working again. While economists debate the value of such projects in recovering from hard economic times, we still reap benefits from many of those projects today. You can still see quite a few of them, if you travel the Great River Road.

One of Roosevelt’s first programs was the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), created under the authority of Emergency Conservation Water Act. It quickly became one of the most popular New Deal programs. Between 1933 and 1942 three million men worked on reforestation, soil conservation, flood and fire control, and constructing state and national parks. In 10 years they restored nearly 4,000 historic structures, developed over 800 state parks, and planted 3 billion trees, among other things.

In the Upper Mississippi River Valley, the CCC was responsible for dramatic make-overs at several state parks, including Perrot, at Trempealeau, Wis.; Pike’s Peak, at McGregor, Iowa; Mississippi Palisades, at Savanna, Ill.; and Black Hawk State Historic Site, at Rock Island, Ill.

Enrollees were mostly men between the ages of 18 and 25, but separate companies were eventually created for older men who had served in World War I. The men lived in camps that mimicked life in the Armed Services, with a military officer officially in charge but with civilians providing the daily leadership. Enrollees received free room and board plus $30 a month, with the expectation that they would send $25 home to help their families. While at the camp, men could get additional training and education for basic skills such as reading and writing, as well as for technical skills like accounting, carpentry, or vehicle repair. Like the rest of the US at that time, the CCC was not integrated. The integrated crew of World War I veterans at Black Hawk Park—now known as Black Hawk State Historic Site—was a rare exception.

At each park, the CCC groomed trails, planted trees, and built a number of park buildings. At Black Hawk the CCC also built two-thirds of the Watch Tower Lodge. The limestone edifice—actually three separate buildings connected by a covered walkway—was designed by Joseph Booten, who also designed several other Illinois park lodges of that era. The lodge now shelters a series of displays about the work of the CCC and daily life at the camp (1510 46th Avenue; 309.788.0177; call to confirm when the lodge is open).

With the economy still in a funk in 1935, Roosevelt created the Works Progress Administration (WPA) by executive order; it would become the largest of his alphabet soup public works projects. During its 8-year run, the WPA spent $11 billion (nearly $200 billion in 2008 dollars) employing over 8 million people in a wide range of projects, from building some 650,000 miles of local roads and highways to improving over 8,000 parks to writing local histories and creating public art.

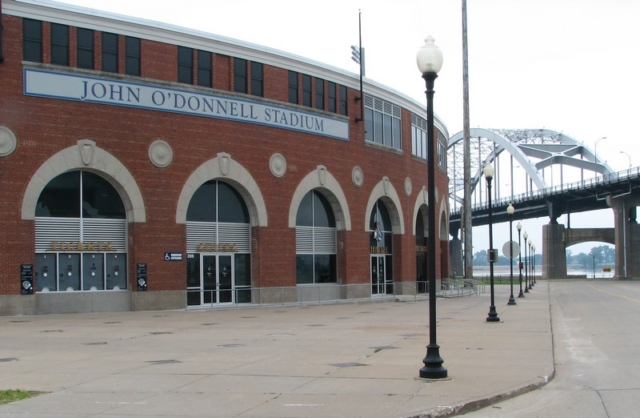

Along the Upper Mississippi, WPA employees built a levee at Prairie du Chien; Riverview Stadium (now Ashford University Field) in Clinton, Iowa; Municipal Stadium (now Modern Woodman Park) in Davenport, Iowa; the stone shelter atop Grandad Bluff in La Crosse, Wisconsin; and several stone structures in Clinton’s Eagle Point Park, including the crenellated watchtower on the south end of the park.

WPA scribes working for the Federal Writer’s Project created local and regional guidebooks such as Galena, Illinois: A History (reprinted editions are still available). The WPA hired artists like Otto Hake, who completed two paintings inside the lodge at Black Hawk State Historic Site.

**Read more about these places and more in Road Tripping Along the Great River Road, Vol. 1. Click the link above for more. Disclosure: This website may be compensated for linking to other sites or for sales of products we link to.

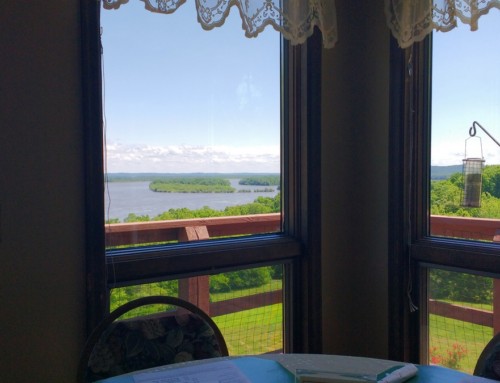

Wisconsin’s Wyalusing State Park, back when it was called Nelson Dewey State Park, benefited from both the CCC and WPA. Between 1935 and 1937, the CCC built roads and trails, began construction on the Peterson Shelter, and performed a variety of conservation activities including erosion control. Trails created by the CCC survived 70 years before portions were washed out in the flash flooding of 2007. The WPA worked in the park between 1938 and 1941 and built several stone picnic shelters, stone walls at lookout points, and finished the Peterson Shelter.

Even with a long list of accomplishments to their credit, the work of the WPA at Dubuque’s Eagle Point Park stands out. The park was created in 1909 but did not take its current shape until Alfred Caldwell, a fan and student of Frank Lloyd Wright and the Prairie School of Architecture, was hired to lead a WPA-funded overhaul of the park. Caldwell completed the design for the renovations in a single day, including the buildings and the terraces along the bluff, then supervised most of the construction.

Other federal programs of the era have stood the test of time, as well. The US Treasury Department’s Section of Painting and Sculpture funded a competition to decorate some of its buildings. Iowa artists Bertrand Adams and William Bunn, friends from the University of Iowa who had each studied with Grant Wood, were selected to paint murals in the Dubuque Post Office after winning such a competition. Their murals, painted a couple of years after the post office opened in 1934, still decorate the interior of the building.

In the midst of one of the worst crises in our country, federal programs like the CCC and WPA reshaped our parks and communities, creating tangible benefits that have lasted for generations. Many of these projects probably would not have been undertaken otherwise.

NOTE: This article originally ran in the May-June, 2009 issue of Big River Magazine. It has been slightly modified and updated for this post.

©Dean Klinkenberg, 2009,2016

Community-supported writing

If you like the content at the Mississippi Valley Traveler, please consider showing your support by making a one-time contribution or by subscribing through Patreon. Book sales don’t fully cover my costs, and I don’t have deep corporate pockets bankrolling my work. I’m a freelance writer bringing you stories about life along the Mississippi River. I need your help to keep this going. Every dollar you contribute makes it possible for me to continue sharing stories about America’s Greatest River!