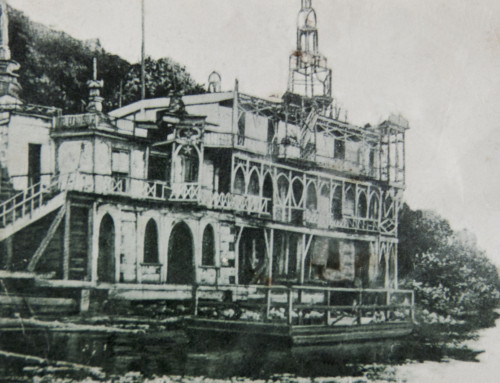

In 1888, well after the peak of the steamboat era, David Niles Wethern and Marion Sparks invested in a new sternwheel steamboat to ply local routes. The Sea Wing stretched 135 feet long and 22 feet tall and was based on the Mississippi River at Diamond Bluff, Wisconsin. Both men piloted the boat, which was used primarily to move log rafts and cargo for short hauls. They occasionally took the boat on excursions to earn a little extra income. One of those excursions would end in disaster, causing the largest loss of life for a steamboat accident on the upper Mississippi River.

On the morning of July 13, 1890, 36-year-old Captain Wethern guided the boat and the attached barge, the Jim Grant (set up as a dance floor), from Diamond Bluff for a day-long excursion to Lake City and back. Captain Wethern’s family went along for the ride, including his wife, Nellie, and two sons, 10-year-old Roy and 8-year-old Perley.

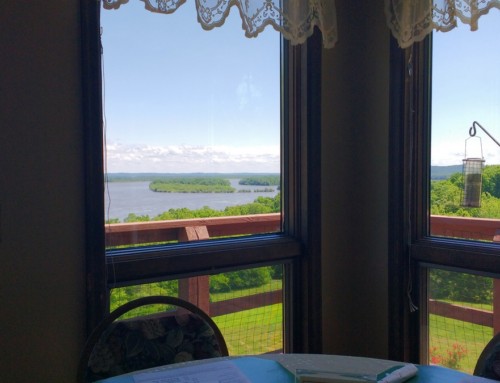

Lake City was hosting a demonstration by the Minnesota National Guard, and a lot of folks wanted to watch. The boat made a few stops after leaving Diamond Bluff to pick up passengers, all of whom paid 50 cents for the daylong excursion. They reached Red Wing at 9:30 where the largest group boarded—165 people. Two hours later, after crossing the wide section of the river known as Lake Pepin, the Sea Wing reached Lake City and sent passengers out to enjoy the day.

Lake City welcomed the passengers with lemonade, popcorn, and ice cream. Some people spread out for picnic meals, while others explored the city’s shops or went over to the military parade grounds. Turbulent weather throughout the day, though, limited some of the fun. It wasn’t entirely clear if the weather would cooperate long enough to get the passengers back home. Captain Wethern blew the horn for boarding around 7pm when there was a break in the clouds, and the boat left Lake City an hour later.

Just 30 minutes into the return trip, a front moved in over the lake and the wind picked up. Captain Wethern turned the boat to head directly into the storm, but it didn’t help. A strong burst of wind roared down and across Lake Pepin, and the top-heavy boat quickly flipped upside down. Passengers who had sought shelter from the storm in the cabin were trapped, and the barge separated sending 50 people floating helplessly away.

The passengers inside the cabin had no chance; they drowned in just a few minutes. Captain Wethern survived by breaking the glass in the pilot house and swimming out. His family wasn’t as lucky, though. His wife and 8-year-old son were among the passengers who drowned. The passengers on the barge fared somewhat better. Some swam to shore, but most were rescued after floating around for a while.

A Lake City boy who was on the boat, Harry Mabey, jumped from the Sea Wing onto the Jim Grant, then to shore when the Grant reached shallow water. He ran nearly two miles to Lake City where he alerted authorities about the accident. Volunteers, including many National Guardsmen, reached the wreck and began the grim task of removing bodies around midnight. Search teams worked for four days to recover them all.

The wreck killed 98 of the 215 passengers; 67 of the dead were from Red Wing. Even more shocking: 50 of the 57 women on board died. While the cause of the accident has never been clearly determined, Captain Wethern received most of the blame (primarily for overloading the boat).

In Red Wing, five thousand people attended the memorial service for the Sea Wing on July25, the worst loss of life in a steamboat accident along the Upper Mississippi River.

Investigators later suspended Wethern’s licenses for “unskillfulness” in operating the vessel and for carrying 30 passengers too many. He was also penalized for not having a separate license to run an excursion with more than 12 passengers. He claimed he didn’t know that he needed a separate excursion license.

Captain Wethern would get back on the river, though, even with his damaged reputation and after losing his wife and son. He salvaged and rebuilt the Sea Wing, running it on the Mississippi for another dozen years before scrapping it. He moved to Prescott with his surviving son, Roy, and remarried in 1905. Roy would go on to a life on the river himself, piloting boats from his home base in Saint Paul. Captain David Wethern died in 1929 and is buried in a modest grave in Diamond Bluff, next to the family he lost on the river.

Community-supported writing

If you like the content at the Mississippi Valley Traveler, please consider showing your support by making a one-time contribution or by subscribing through Patreon. Book sales don’t fully cover my costs, and I don’t have deep corporate pockets bankrolling my work. I’m a freelance writer bringing you stories about life along the Mississippi River. I need your help to keep this going. Every dollar you contribute makes it possible for me to continue sharing stories about America’s Greatest River!