When I was a child, I was fascinated with how things worked. I spent hours taking apart radios, motors—anything I could get, really—to see how they worked. My prospects for an engineering career ended, though, when I realized that I couldn’t figure out how to put anything back together. My poor mechanical aptitude didn’t kill my curiosity, which is good because then I never would have had the chance to climb to the control tower of the Quad Cities’ Government Bridge to see how it works.

The Quad Cities has more than its fair share of historic landmarks: the Clock Tower, Old Main at Augustana College, the empty lot along 12th Avenue in East Moline that was once home for Case/International Harvester/New Holland. The Government Bridge is another of the region’s landmarks, still serving in its original role 120 years after it was built.

The Government Bridge is the third bridge at this general location. The first one was also the first railroad bridge to span the Mississippi River and was just upriver from the Government Bridge; its controversial life only lasted from 1856-1872, shortened by increasingly heavy loads that it was not designed to carry and poor placement that hindered river navigation. A replacement bridge opened in 1872 as a double-decker, with a single rail line above and a wagon road below. Increasing traffic and heavier loads quickly made that bridge obsolete, too, so another replacement was built, salvaging only the stone piers of the 1872 bridge. Completed in 1896, this new bridge would prove to be the masterpiece of its designer, Ralph Modjeski, who is now recognized as one of our best bridge architects.

Modjeski’s bridge joined a series of steel trusses to a 366–foot long center-pivoting swing span that has a camelback shape. The bridge has an 1800–foot train deck on top and a 1600–foot road deck below and is one of only two bridges in the world that can do a full 360–degree turn in either direction. Built for just under $1,000,000, the bridge was jointly owned by the Rock Island Railroad and the federal government until the Rock Island Line went bankrupt in 1980.

I toured the bridge with Mike Dunne, Bridge Supervisor for Rock Island Integrated Services (the contractor that is responsible for bridge operations and maintenance) and a man who bears more than a passing resemblance to Ernest Hemingway; we were joined by Eric Cramer, the Public Affairs Officer for the Rock Island Arsenal.

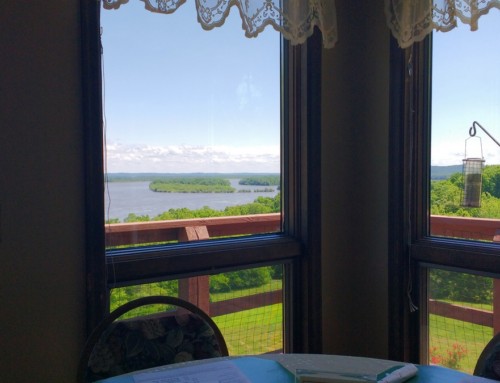

We climbed some 30 feet up two steep sets of stairs to reach the control tower and a commanding view of the region and Lock and Dam 15. The bridge has a crew of six operators/mechanics who man the helm 24/7. Until a school somewhere offers a degree in swing bridge engineering, prospective operators should have a mechanical background and, if hired, expect to work at least four years with the ground crew, learning the bridge from the bottom up. When an operator position opens—and that doesn’t happen very often—members of the ground crew have a huge competitive advantage over other applicants.

Your mechanical background will come in handy because the bridge operator has few high tech gadgets to work with. Here are the basics of how the bridge swings open, as distilled by my non-engineering brain. The lockmaster notifies the operator when a boat is ready to pass through the bridge. The operator blows the horn and turns on warning lights on the rail and traffic decks. He checks the camera monitors (rare high tech additions to the bridge) and, once assured that cars and trains are out of the way, the gates are lowered and all traffic halted. The operator disengages the rollers that link the swing span with the stationary span, causing the bridge to sway slightly, then pulls the levers like the Wizard of Oz, and the bridge begins to turn. As the hum inside the control tower increases and Dunne’s voice steadily rises to a shout, he emphasizes “The bridge has to line up exactly over the guide wall. There’s no room for error.” The operator’s tools to get it right are the same hand brake that has been used for 114 years and his ability to see two red lights line up—one on the swing span and one on the guide wall. As he gets it into position, the span settles into place with very little drift.

After the boat passes, the span is returned to its original position and traffic gets back on its merry way. While it takes up to two hours for a towboat to lock through, the process of opening and closing the bridge must move along quickly, Dunne says. “By contract, we have to average 13 minutes a month” and they’ve met that standard from the beginning. All the more impressive considering they average about 5,000 turns during the ten months the swing span is needed. While their quick turn time is impressive, perhaps more amazing is their record keeping. “We have a record of every turn the bridge has ever made—the name of the tow, the number of barges, cargo—for the life of the bridge except during World War II.”

The bridge still serves as an important transportation link for the Quad Cities, especially for the 7,900 employees of the Rock Island Arsenal. Every day nearly 11,000 cars cross the bridge, plus up to eight trains run by the Iowa Interstate Railroad (at its peak, 80 Rock Island Railroad trains crossed daily). In recent years, inspectors have listed the bridge as “functionally obsolete and structurally deficient.” Ouch. Dunne insists “The bridge has many years of service left.” They have an aggressive routine maintenance program and use their time wisely. “We have to do all of our major maintenance in January and February when the locks are closed and there is no river traffic.” The grated surface on the road deck that was installed about five years ago has added years of life to the bridge, too, by preventing winter build-up of salt and other materials that could corrode the old steel.

Currently there are no plans to build a new bridge. Trying to build something similar would cost upwards of $300,000,000 in today’s dollars; good luck finding that kind of money now. If they ever decide to replace it, though, I’ll be ready. I’ve got a monkey wrench and a desire to rip apart that bridge and see what really makes it tick.

NOTE: A version of this article ran in Big River Magazine (Nov/Dec 2010).

- The downstream end of the lock

- Inside the control room

- Close-up of swing bridge drive train (Library of Congress)

- An early view of the control room (Library of Congress)

- A tow prepares to enter the lock chamber

- A view of the bridge with the swing span open

- Bridge Supervisor Mike Dunne

- A view of the bridge with the swing span open

©2016, Dean Klinkenberg