The problem with living in the present is that we see everything through the only lens we know, which is the world as we’ve known it. When we walk down the street of a town like Iowa’s Keokuk all we see is the world in front of us—run down brick buildings, empty storefronts, ample parking—and we interpret it the way we have learned to, as decay, emptiness, despair. But this place wasn’t always like this.

If we look more deeply we’ll see buildings that hint at grandeur: stately homes atop a bluff—Italianate, Romanesque, Victorian—and elegant commercial buildings on Main Street with ornate brickwork and carved dentils and neo-classical pediments although for some buildings we have to look with the eye of Sherlock Holmes to see past the modern remuddling.

We might think “that’s cute” but we have a hard time understanding exactly what it means, what those buildings represent. Coming from a 21st century mindset, we don’t see those buildings as the hopes and dreams of people of an earlier generation, people willing to bet their money on the future of Keokuk. We don’t see buildings that way, anymore. In our world, people with dreams and money buy iPhones or iPads and dream of the wonders of the next iPhone or iPad. We don’t build elegant buildings that we expect to last for generations; we expect to spend our money on a gadget, then throw it away when the next cool gadget comes along. In a hundred years when someone wants to understand 21st century America, they’ll need to find a dump and dig through the things we threw away instead of walking around our cities to see what we built.

The folks who built Keokuk didn’t have smartphones or tablets; they had brick and stone and wood. And they had optimism, something else missing from 21st century America. Look deeply and you’ll see a city that nurtured a Supreme Court Justice, that gave twenty Jewish families the optimism to build an elegant synagogue, that provided refuge and a home for hundreds of African Americans after the Civil War, that was on the frontier of medicine for half a century, and that was a bustling rail hub with dozens of passenger trains stopping every day. When the immense hydroelectric plant opened in 1913, city leaders bragged about how their town was about to boom. A hundred years ago Keokuk had money and optimism.

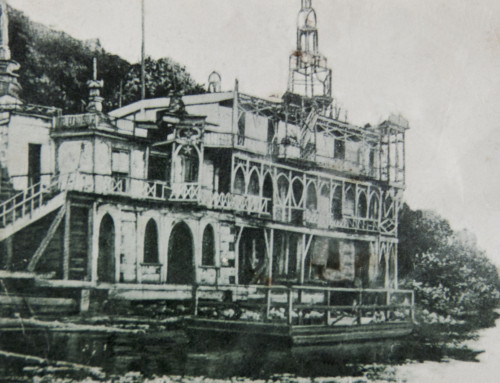

Whether built of brick or wood, time and inattention do a brutal number on human structures and walking around with today’s eyes, it’s easy to see nothing but decay. Buildings that once housed clothing stores and pharmacies and print shops now host taverns (no shortage of those), discount stores, or nothing at all. The pride that these buildings inspired has given way to indifference or disdain. Pockets in the streetscape open up where buildings once stood. The commercial sections closest to the river, closest in time to the founding of the city and its reason for being, are gone, replaced by poorly conceived and executed buildings that were forgettable as soon as they were completed. A terrible error of an era—a 1960s mall—scars the streetscape where the riverbank rises to meet downtown.

The print shop where Mark Twain worked for two years—at the edge of that same riverbank—is now marked by a plaque, a modernist bank, and an empty parking lot. If you walk by that spot today, you may wonder why Orion Clemens (Twain’s brother) opened a print shop in a building that looks like a flying saucer that landed on four brick archways.

But we see all this with 21st century eyes: the need to tear down deteriorating buildings and put up something modern. But even the modern buildings are suffering the same fate. Keokuk today also has shuttered pizza joints and abandoned gas stations. Further down Main Street, the original Wal-Mart is now the Faith Family Church First Christian Church. The edge of town has fewer potholes and newer homes, but its strip malls also have empty storefronts.

With today’s eyes, it’s also impossible to see what comes next. In 1960, Keokuk was a compact and bustling community with a strong economy. If you asked someone from 1960s Keokuk what the city would be like in fifty years, they’d have had every reason to be optimistic. Few foresaw the coming decline, which was more like a slow blood-letting than a full-fledged bust, as the city shed jobs in manufacturing and agriculture and residents gradually moved away.

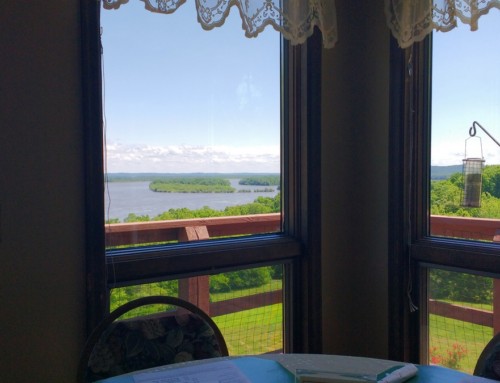

Likewise, if you ask someone from 2010s Keokuk what the city will be like in the 2060s, they’d have good cause to be pessimistic. I hope today’s impressions will be proven wrong. Keokuk, like many river towns, has good bones and good people. River towns, perhaps more than other places, have seen dramatic boom and bust cycles, which builds a resiliency that is not always present elsewhere.

Maybe Keokuk can attract artists by using the scenic location, inexpensive real estate, and busy summer tourist season as a draw. Maybe Keokuk can market itself to folks whose work is not tied to a specific location—thanks to the Internet—and prefer small town life. Regardless, the city, after losing a third of its population since 1960, has to get smaller. It just doesn’t make sense to build new subdivisions and new strip malls on the edge of town while the historic core rots. Keokuk still has enough of its historic center intact to make for an interesting, beautiful, and unique place to live and visit.

I’m neither an optimist nor a pessimist about Keokuk’s future. I can’t see what the city’s fortunes will be like over the next few decades, but I hope that someone with better vision than me can picture a vibrant future and will help this community rebound and bring those good bones back to life and give the folks who live here a reason to feel optimistic about their community again.

**Keokuk is covered in Road Tripping Along the Great River Road, Vol. 1. Click the link above for more. Disclosure: This website may be compensated for linking to other sites or for sales of products we link to.

- Keokuk downtown panorama, about 1900 (courtesy of the Library of Congress)

- Mark Twain worked here!

- Keokuk Hydroelectric plant

- Downtown Keokuk, early 1900s (courtesy of Keokuk Public Library)

- Downtown Keokuk in 2012

- Downtown Keokuk during the Fair, early 1900s (courtesy of Keokuk Public Library)

- Keokuk and the Mississippi River (courtesy of the Keokuk Public Library)

- Keokuk riverfront in early 1900s (courtesy of Keokuk Public Library)

© Dean Klinkenberg, 2012

Community-supported writing

If you like the content at the Mississippi Valley Traveler, please consider showing your support by making a one-time contribution or by subscribing through Patreon. Book sales don’t fully cover my costs, and I don’t have deep corporate pockets bankrolling my work. I’m a freelance writer bringing you stories about life along the Mississippi River. I need your help to keep this going. Every dollar you contribute makes it possible for me to continue sharing stories about America’s Greatest River!

Excellent article!! So good that someone sees the former beauty of Keokuk, and the underlying potential to become something great and unique!

Good blog. Thanks for the perspective.

One small error is that the original Walmart building is now First Christian Church, not Faith Family. Faith Family’s building started as a box store, but it wasn’t Walmart.