Sam Clemens grew up in Hannibal, Missouri. We all know that. Those years provided fodder for his future works of fiction and shaped a good part of his character (and maybe the bad parts, too). We know that, too.

During his life, Clemens related many happy memories of his childhood years, but he also witnessed plenty of tragedy and confronted death at a far younger age than kids do today. He nearly drowned in Bear Creek—twice—and also had a few close calls in the Mississippi River, just for good measure.

So life growing up in Hannibal was a mixed bag, which is a good thing for a future writer. When he moved away in 1854 at 18 years of age, he traveled around the world, then later settled into family life in Connecticut. Time and again, he turned to those childhood memories for inspiration in his writing. The characters in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn were based on people he knew as a child.

Aunt Polly was basically his mother, Jane. His sister Pamela inspired Cousin Mary, while his brother Henry was the model for Cousin Sid. Becky Thatcher was based on Laura Hawkins, the girl who lived across the street, and Tom Blankenship was the real-life Huck Finn.

And it wasn’t just people who served as models in his work; fictional St. Petersburg has more than a passing resemblance to Hannibal. The Cardiff Hill of Tom Sawyer is a real place, though it would have been called Holliday Hill when Twain was growing up. After the book was published, Holliday Hill became Cardiff Hill to Hannibalians—fiction altering reality.

There are plenty of other places around town that made their way into Twain’s works, like the Old Baptist Cemetery where his father and his brother, Henry, were buried. (All of Twain’s family members were later moved to Mt. Olivet Cemetery after it opened in 1876.) The Old Baptist Cemetery served as the model for the place where Injun Joe murdered Doc Robinson. Hannibal is all over Mark Twain (as Twain is all over Hannibal).

Given how many times he replayed and reworked his childhood memories into fictional stories, how did his hometown look when Clemens went back? He only made a couple of return visits to Hannibal as an adult, and it seems to me that each trip must have felt very different to him.

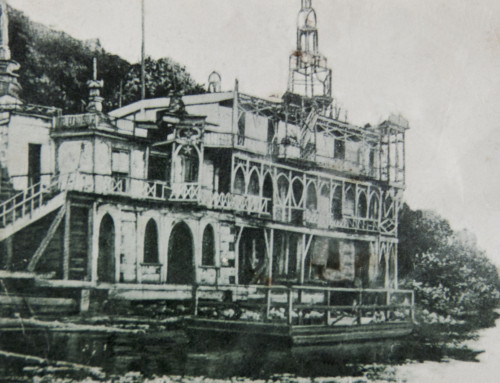

In 1882, Twain traveled by steamboat up the Mississippi River, an excursion he wrote about in Life on the Mississippi. Hannibal was one of the stops on the tour, giving Clemens his first good look at the town in decades.

I had had a glimpse of it [Hannibal] fifteen years ago, and another glimpse six years earlier, but both were so brief that they hardly counted. The only notion of the town that remained in my mind was the memory of it as I had known it when I first quitted it twenty-nine years ago. That picture of it was still as clear and vivid to me as a photograph. I stepped ashore with the feeling of one who returns out of a dead-and-gone generation.

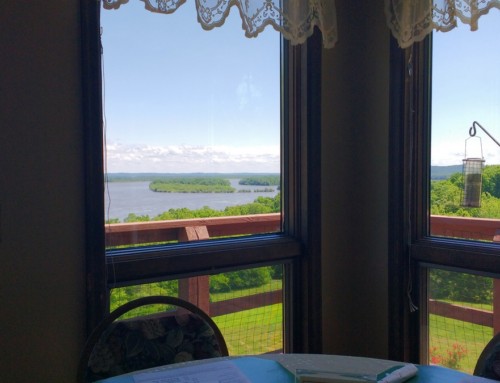

…I passed through the vacant streets, still seeing the town as it was, and not as it is, and recognizing and metaphorically shaking hands with a hundred familiar objects which no longer exist; and finally climbed Holiday’s Hill to get a comprehensive view. The whole town lay spread out below me then, and I could mark and fix every locality, every detail. Naturally, I was a good deal moved. I said, ‘Many of the people I once knew in this tranquil refuge of my childhood are now in heaven; some, I trust, are in the other place.’ The things about me and before me made me feel like a boy again—convinced me that I was a boy again, and that I had simply been dreaming an unusually long dream; but my reflections spoiled all that; for they forced me to say, ‘I see fifty old houses down yonder, into each of which I could enter and find either a man or a woman who was a baby or unborn when I noticed those houses last, or a grandmother who was a plump young bride at that time.’

From this vantage ground the extensive view up and down the river, and wide over the wooded expanses of Illinois, is very beautiful — one of the most beautiful on the Mississippi, I think; which is a hazardous remark to make, for the eight hundred miles of river between St. Louis and St. Paul afford an unbroken succession of lovely pictures. It may be that my affection for the one in question biasses my judgment in its favor; I cannot say as to that. No matter, it was satisfyingly beautiful to me, and it had this advantage over all the other friends whom I was about to greet again: it had suffered no change; it was as young and fresh and comely and gracious as ever it had been; whereas, the faces of the others would be old, and scarred with the campaigns of life, and marked with their griefs and defeats, and would give me no upliftings of spirit.

During my three days’ stay in the town, I woke up every morning with the impression that I was a boy — for in my dreams the faces were all young again, and looked as they had looked in the old times; but I went to bed a hundred years old, every night — for meantime I had been seeing those faces as they are now.

During the 1882 visit, the 47-year-old Clemens wrestled with the passage of time, sometimes losing himself in the warm embrace of the memories of his childhood Hannibal, then left alone to mourn its passage. The contrast between the then and the now was probably at the front of his mind as he walked around town: he had published Tom Sawyer just six years earlier—Hannibal then—and had already started writing Huck Finn, though it wouldn’t be published until 1885. Images of young Becky and Tom were fresh on his mind, even as he was confronted with their grown-up versions.

There may be no way to know this, but I can’t help but wonder how much this visit to Hannibal influenced the narrative of Huck Finn. The return trip to Hannibal wasn’t just a pleasant journey to revisit a few familiar faces. He would also have been confronted with memories of a childhood marked by injustice and death in a town built around the river trade and slavery—both distant memories in 1882—but also the reality of a city that had grown much bigger but not beyond the strict racial hierarchy of his youth. How much were those themes already in his head when he returned to Hannibal in 1882 and to what degree did the trip steer him toward them?

Twain made another visit to Hannibal in late spring of 1902, not long after returning to the US after living and traveling abroad for several years. The second time around—at the age of 67—his visit had a different tone, one laden with nostalgia, as he traveled back to receive an honorary law degree from the University of Missouri.

The visit included a few days in St. Louis where he attended a meeting of former river pilots, including some he had known from his days on the river fifty years earlier like his river mentor, Captain Horace Bixby. One of those men, JK Stotts, who hadn’t seen Clemens since 1862, had fond memories of the young pilot:

Sam Clemens was a mighty queer boy, we all thought. He was a quiet fellow who always drawled in his talk so long that it took twice the time in which another man would say a thing. He was always a good friend, though.

He also spent a full week in Hannibal, “…a city now, a village in my day,” he wrote in his autobiography. (Hannibal counted about 2,000 residents when Clemens moved away in 1854, but nearly 13,000 in 1902.) He was polite and flattering to people he met in town and took joy in recognizing people he knew when he was younger. One of the most memorable moments, Clemens recalled, occurred just as he was leaving Hannibal.

When I was at the railway station ready to leave Hannibal, there was a crowd of citizens there. I saw Tom Nash approaching me across a vacant space, and I walked toward him, for I recognized him at once. He was old and white-headed, but the boy of fifteen was still visible in him.

Clemens and Nash had a history. In 1849, they walked out onto the frozen Mississippi River at night, but the ice started to break up around them as they reached the middle of the river. The boys made their way back toward shore, carefully stepping on large chunks of ice as they floated by. As they were nearly ashore, Nash picked up his pace, slipped, and fell into the frigid water before scrambling to the riverbank. Clemens made no such misstep and reached shore completely dry. Not long after this midnight escapade, Nash got sick, eventually contracting scarlet fever. He lost much of his hearing and, as a consequence, could no longer judge the volume of his own speech. “When he supposed he was talking low and confidentially,” Clemens wrote, “you could hear him in Illinois.”

On that train platform, Clemens recalled that Nash “…came up to me, made a trumpet of his hands at my ear, nodded his head toward the citizens and said confidentially—in a yell like fog-horn— ‘Same damned fools, Sam!’”

At the end of the trip, Clemens traveled to Columbia, Missouri, to receive his honorary degree. The New York Times reported on his address, which included this bit:

Since I have been in Missouri,” said the speaker, “I have distributed more wisdom than ever before, and I am sure that much good will result from my visit. I have had many honors conferred upon me, but I deserved them all. I sometimes suspect when you confer these honors you mean it as a sort of hint that I have been with you long enough. Some of the Eastern colleges seemed to be rather in a hurry about getting me out of the way, and began conferring honors upon me years ago, but as I stated before, I deserve them all, and am always willing to accept anything in the way of honors that you have to offer.

Reading about Clemens’ trip in 1902, it feels like a farewell tour to me, as I suspect it did for Clemens. It was full of reminiscences, most of them pleasant, which is a good thing as life got much harder for him in subsequent years. The same year of his trip to Missouri, his beloved wife, Livy, took and stayed ill until her death in 1904. Clemens never really adjusted to life without her. When a second daughter, Jean, had to be institutionalized in 1906 because of severe seizures and died three years later, life probably never felt more cruel to Clemens and those childhood years in Hannibal so distant.

**Read more about Hannibal and the Mississippi River in Road Tripping Along the Great River Road, Vol. 1. Click the link above to find out more. Disclosure: This website may be compensated for linking to other sites or for sales of products we link to.

©Dean Klinkenberg, 2018