In St. Louis, the riverfront just can’t get any respect. With the St. Louis Rams positioning themselves to move—or to get the public to pay for another new stadium—St. Louis leaders are pushing a plan to build a new stadium next to the Mississippi River that they hope would convince the Rams that we are still worthy of them. Part of the marketing approach for the stadium plan is a claim that it will reconnect the city to its riverfront. Don’t buy it. If built as planned, the new stadium won’t reconnect the city and its riverfront, it will kill the very possibility for at least a generation.

Our city leaders have a persistent lack of vision about what the riverfront could be. In cities around the world, including many cities along the Mississippi River, riverfront property has been transformed from post-industrial wastelands to prime property where people live and work. While many riverfront redevelopment plans began with trails and parks, ideas have matured as riverfront living is increasingly valued. Cities like Minneapolis, St. Paul, and Moline are re-establishing neighborhoods next to the Mississippi River.

Not St. Louis, though. Our business and political leaders look at the riverfront and the best they can envision is a place for some people to party in a parking lot 8-10 times a year.

We have prime locations along the river south and north of the Arch grounds that have been neglected for a long time. The cause of the problem is easy to diagnose: it’s the highway that cuts between downtown and the river, isolating pockets of the riverfront north and south of the Arch. Plans to help the riverfront consistently miss this point, though.

Let’s recap the last century or so of riverfront projects.

Anxious to build a monument to the past, city leaders gave up on the idea of the riverfront as a neighborhood and demolished nearly every building in 40 square blocks, an area that included the footprint of the city established by Pierre Laclede and Auguste Chouteau in 1764. The land sat empty for the next 20 years, until construction finally began on the Arch and the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial.

With the completion of the Arch, St. Louis got its signature tourist attraction just as new highway construction was making it easy for city residents of even modest means to pack up and move to the suburbs. In the spirit of the times, a major highway was built between downtown and the riverfront. What began as the Third Street Highway in the 1950s—displacing some 3,000 residents to widen an existing street from two lanes to six—was transformed into an interstate in 1963 and sunk below grade.

As the Arch attracted tourists, the highways drained residents. In spite of the Arch, the only people who lived along the riverfront were homeless, and planners came to view the whole downtown area, including the riverfront, as a district for entertainment and offices, not for living.

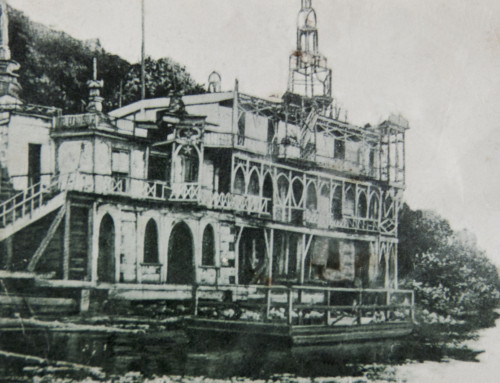

Efforts to preserve and restore Lacledes Landing, a fragment of St. Louis’ late 19th century riverfront neighborhood just north of the Arch—got going in the 1970s. The 9-square blocks are a charming mix of cobblestone streets, cast iron facades, and dense brick buildings. The Landing hints at what the St. Louis riverfront might have looked like if not for the aggressive demolition of the 1930s, but it has never really attracted much business beyond bars, restaurants, and a handful of offices.

St. Louis has known for a while that the riverfront wasn’t all it could be, so various plans came and went—including one with floating islands!—but all we got was a 19-story casino tower surrounded by abundant surface parking.

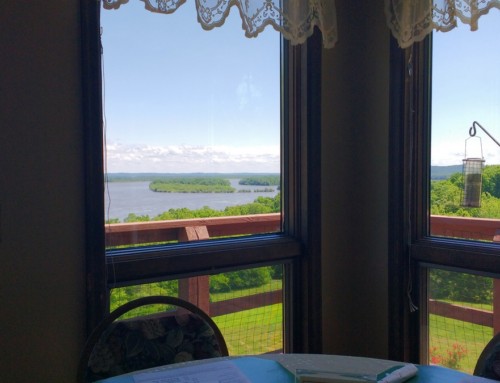

Recently, the 50th anniversary of the Arch’s completion provided momentum for the renovation of the Arch grounds. CityArchRiver spearheaded the effort, an impressive feat in its own right for the way it put together a plan and the money to carry it out, but this project merely enhances a tourist attraction; it does nothing to make the riverfront a place for people to live and work.

Now our business and political leaders propose to build a new stadium north of the casino and Laclede’s Landing. This plan would raze the remaining buildings in the north riverfront and build a glitzy new stadium that would be surrounded with more acres of surface parking, enough for 10,000 cars.

**Read more about St. Louis in Road Tripping Along the Great River Road, Vol. 1. Click the link above for more. Disclosure: This website may be compensated for linking to other sites or for sales of products we link to.

Parking lots, casinos in towers, and stadiums do not reconnect cities to riverfronts; only neighborhoods do that. Building a new stadium and parking lots is costly not only for the poor use of limited public and private dollars but also for the lost opportunity costs—for what can’t be built there once the stadium is in place.

The inability to see prime riverfront property as an area where people might want to live and work is a failure in vision and leadership. The future of the city depends on nurturing and building neighborhoods. Instead of paving over more land near the river for the short-term storage of cars, we should use the land to build a real riverfront community.

And there’s a simple way to make this happen: remove the highway that cuts off downtown from the river and restore the street grid. That’s all. Once that’s done, let people—individuals, small companies—get to work building the spaces that will restore the riverfront neighborhoods. We don’t need a billion dollar mega-project to make it work; we just need to create the conditions that will make people want to build and live there.

The idea of removing a highway may seem shocking and impractical to many in Missouri, but it has worked so well in other cities (Milwaukee, San Francisco, New York, Portland) that the idea can no longer be considered revolutionary: it’s a best practice.

The construction of the new Mississippi River bridge (The Stan Span) and the consequent rerouting of some interstates presents a great opportunity to remove the downtown highway and restore the street grid. Even though we haven’t had the leadership or vision to advocate for it so far, it’s not too late.

The Arch helped create an international marketing symbol for St. Louis but it came with a hefty price: the obliteration of a neighborhood. Let’s turn St. Louis into an international destination where people want to stick around and explore the fabled Mississippi River after checking out the Arch. A stadium and parking lots won’t make that happen, but vibrant riverfront neighborhoods will.

© Dean Klinkenberg, 2015

Community-supported writing

If you like the content at the Mississippi Valley Traveler, please consider showing your support by making a one-time contribution or by subscribing through Patreon. Book sales don’t fully cover my costs, and I don’t have deep corporate pockets bankrolling my work. I’m a freelance writer bringing you stories about life along the Mississippi River. I need your help to keep this going. Every dollar you contribute makes it possible for me to continue sharing stories about America’s Greatest River!