NOTE: This article originally appeared in the Jan/Feb 2010 issue of Big River Magazine.

When the Army announced plans to raze an aging limestone warehouse at the Rock Island Arsenal, around the time of World War I, locals who viewed the building with great affection convinced the Army to save it.

The building, known as Storehouse A, had exceeded its planned lifespan and played a diminishing role in the arsenal’s mission. In 50 years, the structure, whose construction had been fraught with delays, cost overruns and shoddy work, had evolved into a local landmark rising above the floodplain and had become a part of the lives of the many people who consulted its clock during their daily routines.

In July 1862, in the midst of the Civil War, Congress authorized the creation of three new arsenals: at Indianapolis; Columbus, Ohio; and Rock Island, Illinois. At Rock Island, the new commander, Major Charles Kingsbury, received a plan for the first building, a warehouse for weapons and ammo to be called Storehouse A. The building, nearly identical in design to the storehouses at the other two arsenals, would be constructed simply to provide storage for the Army in the remaining years of the 19th century, explained Park Ranger Don Bardole during a tour of the building and its history.

Construction began on September 3, 1863. The foundation was excavated by November. From that point on the project proceeded in fits and starts.

Construction during wartime was complicated by skyrocketing inflation, the scarcity of reliable contractors, and shortages of labor and materials that were exacerbated by the construction of a prison nearby for captured Confederate soldiers. Stone for the building was quarried from nearby LeClaire, Iowa, then floated downriver on barges, but historically low water on the Mississippi River slowed delivery. (The 1864 water level is the reference point used to calculate a river level of 0 feet.) After only the foundation and some of the first floor had been completed, Major Kingsbury, deeply discouraged by the slow progress of construction and a lack of support from higher ups, requested a transfer, which was granted in June 1865.

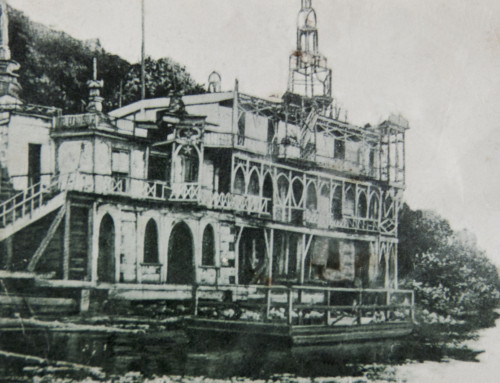

His successor, General Thomas Rodman, replaced faulty girders and iron columns, and brought Storehouse A to completion in 1867. Rodman made several changes to the design of the building, such as adding a gabled roof and palatinate windows at each end. Rodman’s changes shifted the basic design aesthetic from Greek Revival to Italian Renaissance. The finished structure was an impressive sight: a building with thick limestone walls 180 feet long by 60 feet wide, with a tower rising six stories high.

While impressive, it would be just another warehouse were it not for the six-story clock tower. The tower was originally built to support a hoist to lift supplies up to other floors. Two other hoists were installed at the east and west ends. The east one is still visible, complete with wheel, winch, rope and hook. To complete the tower, Rodman purchased a clock from renowned New York manufacturer A.S. Hotchkiss. At the end of 1867, Hotchkiss himself traveled to the arsenal to install the clock and train its first operator, W.J. Pratt. In 1907 Pratt’s family immortalized him by noting his service with a bit of graffiti on the west wall: “Carrie Passig and daughter Ruth and Hattie Pratt come with Papa Pratt to see him wind clock. Papa started to wind clock in 1867 and missed winding 3 times in 1867 to 1907.”

This remarkable clock, original parts still intact today, has operated nearly perfectly for 140 years. The works sit in a cast-iron frame behind a wood-and-glass enclosure. The clockworks connect to a central gear in the middle of the room that drives four spurs with a rod to each of the four clock faces. Each face is 12 feet in diameter (twice the size originally planned) with six-foot minute hands and five-foot hour hands. Each clock face has 12 round glass windows at the hour points through which one can watch the hands move (and get great views of the Quad Cities). The clock’s pendulum sinks nearly two stories deep, gently swinging a 350-pound weight.

The clock was originally wound by hand, a process that took two men 20 minutes once a week. The winding is now done by an electric motor that was installed in the 1950s. When Hotchkiss installed the clock, he set it to local time (the actual time based on the sun), even though most surrounding towns used railroad time (aka “Chicago time”). As a result, the Arsenal clock was typically 13 to 15 minutes behind the clocks in neighboring towns. (When the clock was installed, the United States had some 100 different time zones. National time zones were not officially adopted until 1918, although the railroads established time zones much earlier to facilitate cross-country travel.)

Ironically, the space provided by Storehouse A was no longer essential by the time it was finished, because it stood outside the gated grounds of a much larger armory to the east that had been designed by Gen. Rodman. Completely empty by 1930, the Army Corps of Engineers began using the storehouse in 1931 to house workers building Lock and Dam 15. In late 1934, the building became the headquarters for the Corps’ Rock Island District. It now provides office space for nearly 300 employees.

The Corps’ district library is tucked away in a corner of the basement, just past the break room. The library, one of the under-appreciated assets in the region, is housed in a nondescript room with a very low drop ceiling. Most of the collection is stored on 11 compact shelving units that run about 16 feet long and fill about a third of the library. Bob Romic, district librarian, said the library is a rare resource, even within the Corps: “Only half of the districts have a library, and half of those are contracted out.”

Founded in 1975, the library contains a serendipitous collection of items, some long-forgotten and rescued from dark corners of government warehouses and some donated by long-time employees. The core of the collection is an assemblage of film, photos, and documents from the construction of the lock-and-dam system. Most of the library’s 500 photo albums are from that era. The library also has a number of photos of the Upper Mississippi River before construction began, including dozens from the 1910 book Views of the Upper Mississippi. Other gems include several original photographs of the Mississippi Valley shot by Corps draftsman Henry Peter Bosse at the end of the 19th century. Unfortunately, few of his glass negatives have survived. The library also has an impressive collection of navigation maps that go back to the 1800s, including a few that were hand-drawn by Bosse.

Old employee newsletters provide a glimpse into work life at the Corps. In 1934, The Safe Channel published updates on lock-and-dam construction, injury reports, health tips and small-town-newspaper-style accounts of employees’ personal lives. In contrast, the World War II-era Clock Tower Post was probably an unofficial newsletter, judging by the front-page image of a woman sitting on a colonel’s lap.

This structure conceived for temporary storage grew into the role of timepiece for the region before attaining landmark status and a place on the National Register of Historic Places. The current owner, the Rock Island District of the Corps, is working to ensure that it will be around for future generations of Quad Cities residents to enjoy, according to Bardole.

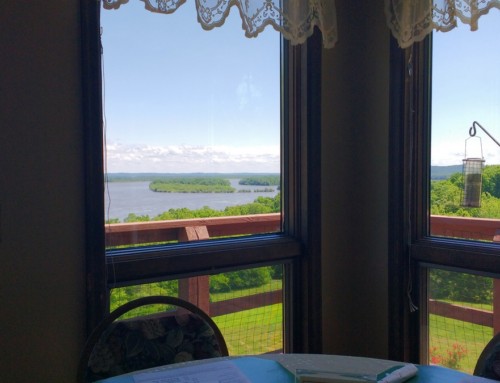

The Corps leads tours through the Clock Tower periodically, but reservations are required (800-645-0248 or 309-794-5338). You can also arrange tours for other times, if you have a large group and book in advance. In winter, the Corps hosts eagle viewing events in the Clock Tower (eagles nest in the slough west of the building). Top floors are not heated, so be prepared for cold temperatures and climbing several sets of stairs. The views from the tower are the best in the Quad Cities.

Appointments to use the archives are strongly recommended (309-794-5884). The library is open weekdays 8 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., except for federal holidays. Many of the photos and maps have been digitized, but they are not yet available online.

With the new security procedures now in place at the Rock Island Arsenal, visitors must show a photo ID at the gate and wait for a background check to be completed. Arrive at the Arsenal early enough to allow for the extra time to complete this process.

© Dean Klinkenberg, 2010, 2016