A couple of weeks ago I praised the cities along the Upper Mississippi River with the the best riverfronts. Now it’s time to prod the cities that could do a lot better. I resisted calling these the “Five Worst” because I think any place that provides a decent view of the Mississippi River shouldn’t be stuck with the adjective “worst.” But, the sad truth is that my list of least favorite riverfronts was longer and harder to narrow down than my favorites. Many cities along the Upper Mississippi provide a ho-hum riverfront experience.

Two problems are especially common. The river is not easy to get to and, if you do manage to get close, the city is cut off from the river by a giant flood wall, levee, or highway. These flood barriers, especially the walls, create a feeling of being isolated from the rest of the city, which probably scares the dickens out of some people, so few people linger around the river. I don’t mean to downplay the damage that floods can do, but let’s face it, the river is in flood stage a small fraction of the time, yet we create structures to protect against the worst-case scenario with giant concrete walls and tall earthen levees. We treat the river like a crazy uncle at a family reunion, so embarrassed by his presence that we lock him in the basement permanently. We have a lot of creative people in this country. Surely we can come up with better solutions.

The city of Davenport, Iowa, for example, has taken some flak for refusing to build a permanent flood barrier, but I think their solution has worked pretty well. Most of the riverfront is green space that is allowed to go under during periods of high water; temporary flood walls of sandbags are built when the water gets high enough to threaten buildings. From all I’ve read, this has been a cheaper solution than building and maintaining a permanent flood wall or levee, even with moderate flooding becoming more and more of a regular event.

The cities along the Mississippi River exist because of the river and need to embrace it. After a century of turning their backs on the river, it’s time our river towns pivot again and embrace the river, while making a serious effort to find new solutions to flood mitigation that don’t segregate the river from the rest of the city.

So here’s the list of places that could do a lot better. Visit them anyway but don’t be shy about expressing your wish that these riverfronts could be a lot better.

5. Prairie du Chien (Wisconsin)

I agonized over this choice. I like Prairie du Chien; really. I also understand that the city is in a tough spot. The historic center of the city is St. Feriole Island, where European settlement began in the 1700s and where Native Americans met and lived long before that. The island flooded some 40 times since 1785, but, for two centuries, folks just coped with it. In the late 1970s, however, after another big flood, the federal government began a new program to buy property in flood-prone areas and move people out. While this worked to mitigate property damage from flooding, it left behind a mostly barren landscape that surrounds Villa Louis, a gem of a 19th century home that was left intact. A few things have been added to the island over time like a (growing) sculpture park and ball fields, but most of it feels empty and forbidding. Honestly, though, if Prairie du Chien had trails or public places near the river and backwaters away from St. Feriole Island, they wouldn’t be on this list. But they don’t.

4. Louisiana (Missouri)

If you like blacktop and tin sheds, you’ll love this riverfront. What a shame, too. Louisiana is an old river town with beautiful 19th century brick and stone buildings set among rolling hills next to the river. The former front door to the city, the riverfront, is clearly an afterthought to town leaders. In contrast to the Iowa communities of Bellevue and Guttenberg that I highlighted among the best riverfronts, Louisiana does almost everything wrong. Much of the riverfront through town is not accessible. The small riverfront park near downtown is little more than a parking lot. When you get there, the only thing to do is park your car and stare at the river. There are no trails (legal ones, anyway), no green space to soften the transition from river to city. A gazebo and picnic tables are set atop rocks. It is possible to walk from downtown to the river, but I didn’t see anyone doing so. Why would you? To sit at a small picnic table and run your feet across the gravel? While the lack of a flood wall or levee is a good thing, the scenery just behind the parking lot is not inspiring or inspired, just a few cheap tin sheds. Louisiana does not put its best face toward the river.

3. Winona (Minnesota)

Winona’s earliest European settlers were steamboat captains, and the city was an important river port for decades. You wouldn’t know that today. The downtown riverfront is the red-headed stepchild of Winona. If you get past the levee and flood wall that cut off the river from downtown, you are greeted by crumbling gray concrete and emptiness. The riverfront is rundown and uninviting. In fairness, there are other places in Winona with park-like settings along the river (Prairie Island, Latsch Island), but the downtown riverfront is so disappointing for a city with a rich river history, they make the list for that reason alone.

2. Brainerd (Minnesota)

Brainerd, like most Mississippi River communities, began because of the river. In Brainerd’s case, the city sprung to life when the Northern Pacific Railroad built a railroad bridge at this site in 1871. Brainerd quickly developed a dependence on the railroad (even in the 1920s, 90% of the jobs in town were tied to the railroad), which may be part of the reason it’s so hard to find the Mississippi River, even though it cuts a winding path through the heart of the city. And that’s why it comes in at number two: Brainerd has virtually no riverfront, at least not one open to the public. The only reliable places to see the river are the bridges that span it and one small park—Kiwanis Park. There is a glimmer of hope. A former industrial site along the river will probably become a new 2000-acre park on the northeast part of town—the Mississippi River Northwoods Habitat Complex. That’s a good start, but it’s mostly on the outskirts of town. To get off the list, Brainerd needs more riverfront access in the heart of the city.

1. St. Louis (Missouri)

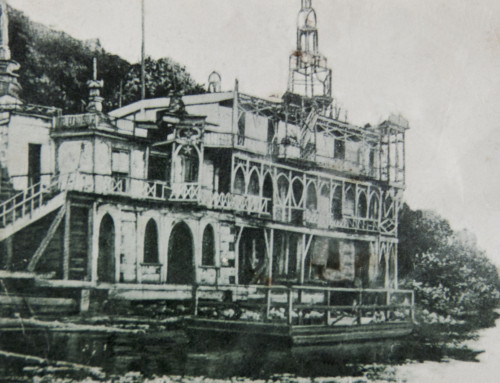

I love my hometown. It has a big history with attractive historic neighborhoods, a rich music scene, and an affordable cost of living. We also have a riverfront that is a terrible mess. The city began turning its back on the river in the late 19th century, not long after the graceful Eads Bridge opened and helped the railroads drive the last nail in the coffin of the steamboat trade. We’ve disrespected our riverfront (and river history) ever since.

The biggest insult was the 1930s-era decision to level 40 blocks of riverfront buildings, many built before the Civil War, in the hopes that a park would be built. Yes, that effort eventually resulted in the Arch, a monument that I love but one that came at too high a price. The construction of the Arch obliterated the heart of the original city, including the spot where Pierre Laclede laid out the infant city in 1764. We tore down our tangible history to build a monument to it.

The Arch grounds also created a barrier to the river. Sure, there are places to look down on the river from the Arch grounds, but few people take the grand staircase down to the levee, and why would they? Once you’re there, there’s not much to do or see and the structures that do exist are, for the most part, Third World. You can take a helicopter ride from a dingy barge with a single-wide for an office or wander to the food booth for authentic St. Louis fare like cheeseburgers and hot dogs. It’s not a total loss, though. You can walk on the cobblestones of the original 1840s levee and catch a riverboat cruise, but those kinds of experiences are the exception.

I suppose I should feel optimistic about the future of the St. Louis riverfront, now that we have a redevelopment plan that includes a lot of pretty pictures of its mostly pedestrian ideas. But I’m not. This is at least the third riverfront redevelopment plan since I moved to St. Louis in 1988, and none has yielded anything tangible.

I understand that there are challenges to riverfront redevelopment, like prioritizing who gets to use the river. Some redevelopment efforts in the past were torpedoed by the US Army Corps of Engineers because of concerns about the impact on navigation. At St. Louis, shipping interests trump all other river stakeholders.

All this is bad enough, but the other major problem in St. Louis is poor access to the river. The riverfront bike trail runs north from downtown to the historic Chain of Rocks Bridge and is a local treasure, but south of downtown, there are very few places to (legally) get near the river.

Sorry, St. Louis. We can do a lot better.

We need better riverfront spaces to connect our present to our past, to remember the reason our cities are where they are, to remind us city folks that there is a natural world away from the mall, and to give our people public spaces to gather and linger, a place to sit and think while watching the world flow by.

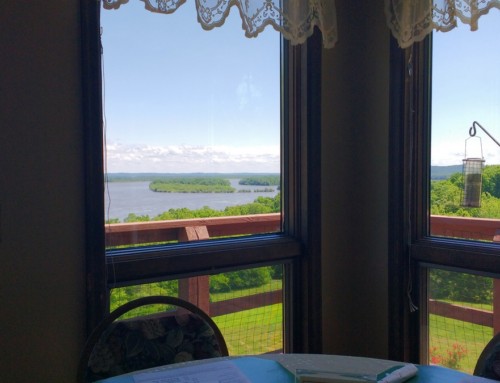

- The LaChapelle House has been awaiting restoration for a long time

- The former Dousman Hotel, also awaiting restoration

- Louisiana’s blacktopped riverfront park

- Another view of the Louisiana riverfront

- The old cobblestone levee is often used as a parking lot

- Park on the levee, ride a helicopter

- The original 1840s levee

- A giant concrete wall separates the Arch from the riverfront

- Looking south on the St. Louis riverfront

© Dean Klinkenberg, 2011

First, thank you to all the folks, probably from Louisiana, who took the time to read my post about riverfronts that need help and to those who also took the time to compose a reply. It’s never fun to have your hometown criticized, especially by someone who doesn’t live there. It goes without saying—but I’ll say it, anyway—that my comments are strictly about the riverfront and not the rest of Louisiana or the good folks who live there and who may want to buy a book from me someday.

I understand the challenges that exist for many communities, especially smaller ones, as they try to find ways to redevelop their riverfronts to attract visitors and meet the needs of residents. These are challenging economic times and there isn’t a lot of money floating around to help with riverfront projects. I hope the good folks in Louisiana (and other places), though, can come up with creative solutions that give visitors a reason to spend time along the river instead of just taking a quick look and moving on.

I write from the perspective of someone who drives along the Great River Road to visit communities and see the relationship between the river and the community. I like to spend time near the river, to walk along its banks, to get a sense of the role the river played in the community’s history. In Louisiana, I found it nearly impossible to do much of that. I’m sure that boaters appreciate having a place to park their cars and trailers, but a big parking lot next to the river does not entice a visitor to stick around.

I look forward to visiting Louisiana during one of the festivals, but I think the better gauge of how communities value their riverfront is by visiting on the routine days. Anyone can clean up and put on a good show when you’re expecting company for Thanksgiving dinner, but how well do you take care of your home when it’s just you and your family around?

It has nothing to do with big city versus small city, either. The place I picked as needing the most help was St. Louis, which, the last time I checked, had a few more residents than Louisiana. On my list of the best riverfronts, three of the six places were communities about the size of Louisiana. It is possible to do better.

I wish you the best.

As a native of Louisiana Missouri I was disappointed with your remarks about Louisiana. Yes the river front is not up to the standards of a big city,however most monies and labor involved in what is done in this park is volunteered, Happily, by the residents of this city. A certain electrician did a lot of the electrical work to make this area safe after he had put in a full days work. Also the history of the tin sheds as you call them are very exciting if you take the time to check them out. 1 building processed mussle shells so you could have the fancy buttons you wear on your shirt.and the fancy mother of pearl jewelry that your wife wears. So as 1 famous Missouri resident (Mark Twain once wrote, DONT TELL ME HOW FAR YOUR FROG JUMPS, SHOW ME )

Thank You .. An Oklahoman who is waiting to die so his mortal remains can be placed so he can look down on the Mighty Mississippi.

I’m disappointed you felt our Louisiana, MO riverfront was so shabby. It is actually a work in progress that many community ‘leaders’ and civic groups are working on–contrary to your assumption. Many thousands of dollars of materials and labor have gone into the riverfront area in the past few years to replace the tired worn out pavement, remove old unsightly electrical services and place them underground to the two gazebos (making them flood proof whereas before they were not), installing new historical themed lights and ripping up the old pavement where the trees and benches/tables are and replacing it with gravel until the appropriate pavers/landscapers can be funded. Just 4 years ago this entire area, past the railroad tracks, was under several feet of water for more than a month. In the intervening time, a great deal has transpired. Large, very old trees were removed (most were diseased and/or dying) and replaced with new trees in more appropriate locations (one was actually in the drive area before) and our Historic Preservation Association created the memorial paver walkway to the riverfront access steps. Hopefully the longterm work on this area will meet with your approval, but in the mean time please know that assuming our city doesn’t care about the riverfront is erroneous. Additionally, I’d like you to see the boat trailer parking lot on any given spring/summer/fall weekend. It is full as is the grassy knoll between South Carolina and Georgia Streets. Boaters enjoy the ease of parking in the area with the ready access to the river. There now exists a multiple slip wooden boat dock just south of the ramp as well to accommodate those that would like to park for a while and enjoy the downtown area–which does happen. Visiting a small town riverfront area in November when there’s no activity happening doesn’t give a very clear view of the place. Try visiting us again on the third weekend in October during Colorfest. Or maybe you can visit that website http://www.louisianacolorfest.com and see just how that area is utilized for the community then. Both a large car show and a motorcycle show take place there. On the 4th of July we have the ONLY fireworks display in Pike County here. With the railroad tracks (which aren’t moving!), access is limited and we’re lucky to still have two streets that cross the tracks to the riverfront. The railroads have wanted the town to give up one of them for many years now.