Keokuk, Iowa has lost 5,000 residents—a third of its population—since 1960. While Keokuk’s decline is dramatic, many of its neighbors have also been losing population during the same period. The reasons aren’t all that complex, really. Consolidation in agriculture has led to bigger farms and fewer farmers (and farm families), there are fewer manufacturing jobs, and cars and highways have made it easy to drive to the next big town to shop instead of doing it at home.

I recently wrote about how difficult it is to see what these places used to look like, to see what forces created them and perhaps worked against them in recent years. I didn’t have any great ideas that might help turn around the city’s fortunes, but I haven’t stopped thinking about it.

Well, now I have an idea. It may help, it may not, but maybe it’s a place to start. I’d like to see a river corridor that embraces and celebrates the ethic of “all things local.” I’d like to see the villages, towns, and cities from Hannibal to Burlington become model communities for what it means to “go local.“ Here are some examples.

Food. The region is surrounded by the richest farmland in the world. If there’s a region that should thrive on local food, it’s here. It’s time for restaurants and home cooks to begin preparing food that uses seasonal ingredients grown by local farmers. In Wisconsin, one way this has been put into practice is through “pizza farms”: a local farmer makes pizza one night a week using ingredients that are mostly (or entirely) from their farm. A to Z Produce near Stockholm is a good example. The great thing about these pizza farms is that their primary audience is people who live in the area, not tourists, so they have a steady, reliable business that is supplemented by visits from tourists during peak summer months.

Beer. Most of the communities in this stretch of the river had their own breweries in the 19th century. The raw materials are still abundant in the region. Locally-brewed beer could not only supply local drinking establishments but would be of interest outside of the region, too, if done well.

Wine and distilled beverages. Some wineries already exist in the area, but it’s time to think bigger and start producing distilled beverages, too. Mississippi River Distilling Company in LeClaire is a good example of what’s possible. They buy most of their raw materials from local farmers, so everything they produce (bourbon, gin, etc.) has a local angle. Along this stretch of the river, we grow a lot of grains and have a wealth of fruit; let’s go crazy distilling. We also grow a lot of apples; I’d like to see some places produce hard ciders, like Maiden Rock Cidery and Winery in Wisconsin.

Art. The region is rich with inspiration, real estate is cheap, and each community has grand old buildings that have been abandoned that would make great work/live spaces for artists. Sculptors, painters, musicians, photographers, fiber artists, writers, jewelry makers…come on down! There is no shortage of inspiration in the region: the Mississippi River, local characters from today and the past, geodes, more weather than you can shake a stick at, abandoned buildings; the list is impressive.

Power. Keokuk has a hydroelectric plant right next to it but doesn’t get any of the power it generates. Sorry about that. We’re power hogs in St. Louis. But, there’s no reason Keokuk can’t look for ways to produce more of its own power. Heck, just up the road ten miles, Siemans makes wind turbines. I haven’t seen any of those in the area. Maybe it’s time. Maybe it’s also time to invest in solar panels. We do get a fair amount of sunshine in the Midwest.

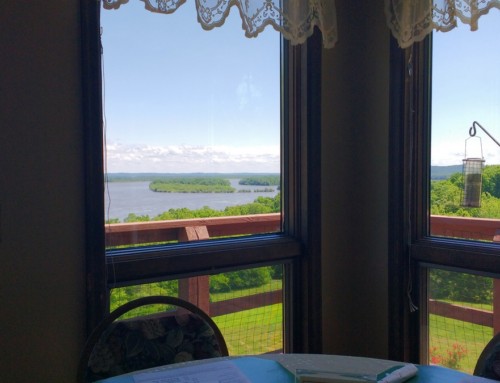

Lodging. Instead of trying to lure another chain hotel, why not develop smaller, locally-run accommodations (inns/B&B/hostels), preferably close to the historic center of the city and the river; some of those empty buildings would be perfect as small inns. They don’t all need to be boutique accommodations, either. Some could specialize in budget lodging, while others could offer bigger spaces for families.

Transportation. The whole region could be connected with dedicated bike/pedestrian trails along both banks of the river and signed canoe routes. A joint marketing effort could promote weekend packages for visitors who want to paddle or peddle their way from Burlington to Hannibal, stopping along the way for fresh seasonal food and staying in locally-run accommodations powered from local sources.

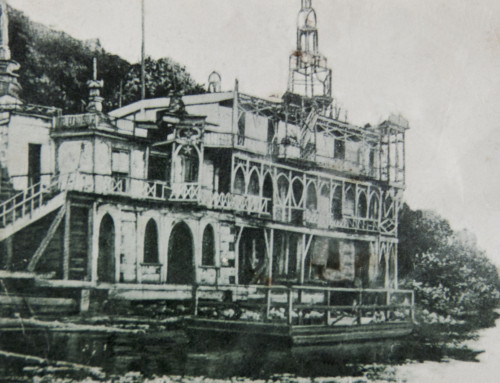

History. Historical travel is a big chunk of the domestic travel market, and each of these communities has been through a lot, with stories that would interest a lot of visitors (as well as many residents). Hannibal already gets a lot of mileage from their Mark Twain connection; other communities could find ways to better capitalize on their own past. The thing is, it takes more than a historical marker to keep people’s attention, and placing a marker at a parking lot where a building used to be is just a downer. Communities need to find ways to integrate their local history with who they are today. Maybe we start small. Come up with a few festival ideas that grow out of the community’s past. Here are some possibilities:

• Fort Madison could have an Average Man (or Average Person) festival every year in honor of Ron Gray, who was selected by American Magazine as the country’s Average Man in 1927.

• Many of these communities also were in the middle of the fight over slavery and emancipation; maybe they could join together for an Underground Railroad week.

• Abe Lincoln touched many river communities in this area. How about a weekend festival of Abe Lincoln’s Mississippi River?

These are just a few ideas to get started. I’m sure you have your own. I suggest for the whole effort we create a brand: the Pride of the Mississippi Valley (or something like that) to tell the outside world what’s going on.

Some of this is obviously aimed at attracting tourism, and there are obvious reasons for this: tourists already visit many of these communities; each has the Mississippi River as a natural draw; and, this corridor is within easy reach of major population centers of Chicago, St. Louis, and Des Moines, with the Twin Cities, Kansas City, and Indianapolis not much further away. Amtrak also serves three of these communities already (Quincy, Fort Madison, and Burlington).

But, while this corridor could see increased tourism from this effort, it will fail if it doesn’t deliver real, everyday benefits to the folks who live in these communities, whether it comes from offering a source of income, an improved quality of life, or something else. It’s easy to forget. This isn’t about tourism; it’s about improving the lives of the people who live in these communities.

Will these ideas turn these places around tomorrow? No. It will take some time. Sam Clemens didn’t become Mark Twain in a day. But maybe over time local folks will patronize more local stores and restaurants instead of chains and big box stores (you don’t build local character by adding another Applebee’s or Walmart). Maybe it will nurture the survival or return of smaller farms; not everyone needs to grow corn for ethanol, after all.

To make this work, though, we will need strong leaders in each community who are willing to make strategic and reality-based decisions about the future. It’s time to throw out the false prophecies of growth, namely the belief that if you are not growing, you are dying. These communities are not dying, but they have been getting smaller and may continue to lose population in the near future. Civic leaders must come to grips with that reality and concentrate their limited resources on strategies that strengthen their existing assets.

So let’s go local in a big way. What are you going to make?

© Dean Klinkenberg, 2012